reviews

2014-08-28

‘Stopover’, Dr Asha Chand, June 2008

“ ... Chaudhry has become Ba’s local hero and a legend in his own right as an advocate for the country’s sugarcane farmers, himself resisting any temptation to flee the country.”

STOPOVER: A puncture in Fiji Indians’ journey

They say pictures say a thousand words … Bruce Connew’s ‘Stopover’, a real puncture in the journey of migrant Indians from Fiji, a majority of who share a common history of life on sugarcane fields, does just that.

Capturing the essence of daily farm life, the book, through a collection of photos, documents the longings of Fiji’s landless Indians. It completes the migration cycle in one physical place, Vatiyaka, a small village tucked away amid rolling hills, facing the vast Pacific Ocean, in the heart of Ba. Ba is a rural town in Fiji, the childhood home Fiji’s first Indian Prime Minister, Mahendra Chaudhry. Although Chaudhry’s government remained in office for only a short spell, being removed at gunpoint during the May 2000 coup, staged by George Speight, Chaudhry has become Ba’s local hero and a legend in his own right as an advocate for the country’s sugarcane farmers, himself resisting any temptation to flee the country.

Connew lives the experience as a journalist, capturing some of the casual and carefree moments of farm life. He reminds the reader of Tom Wolfe’s New Journalism theory where hacks leave their comfort zone to relate stories back to audiences in their raw essence.

The photos are juxtaposed in no real sequence, reminding the reader of the haphazard and punctured life of Fiji Indians with several stopovers along the way, as the island Paradise is still reeling from the pain of four coups within 31 years, while simultaneously dealing with the ingrained coup culture that disrupts life and livelihood at every corner.

My own sequence of reading the photos begins with the two-months-old baby lying swaddled on the floor of her parents’ home. The bare mattress made from dried coconut husks is thrown on a lino covered floor, with two pairs of women’s feet (obvious from the edges of their floral skirts) in the background. The baby, Sharina Kumar, is asleep, oblivious to the tumultuous world around her. On the next page, Ravindra Kumar ‘calms’ his first born, Ashna Devi. The caption tells the story of Kumar’s niece, Joti who is to marry a Fiji Indian boy from Canada. The kitchen, out-built, is made of 44 gallon drums flattened to make the walls, with tin roofs, speaks volumes about the conditions of living on a farm. The photos of children playing their natural antics while trying to get a car, obviously wrecked, into gear, pulling goats by their ropes, soaking in the fun of women singing and dancing by the creek, all take me back to my own days as a little girl growing up in a village, Tavarau, also in the Ba district, popularly known for its road side fresh fish and vegetable stalls.

Shayal attempts to fly with arms stretched-out. This photo, taken on a makeshift soccer field echoes the desire among even innocent children, who are not even familiar with the political or social climate that has engulfed Fiji, to migrate. While Shayal does so in the foreground, a small boy, perhaps five, sits content with a soccer ball in his hand. Another child, of a similar age, paces on the bare earth, gazing into the horizon. All these natural poses of the children displays some form of dreaming, so typical of childhood.

The photo of the man shaving reminds me of one terrifying moment in my own childhood when I broke the only mirror my family had. It was about 2 x 2 cm in size with a red square frame.

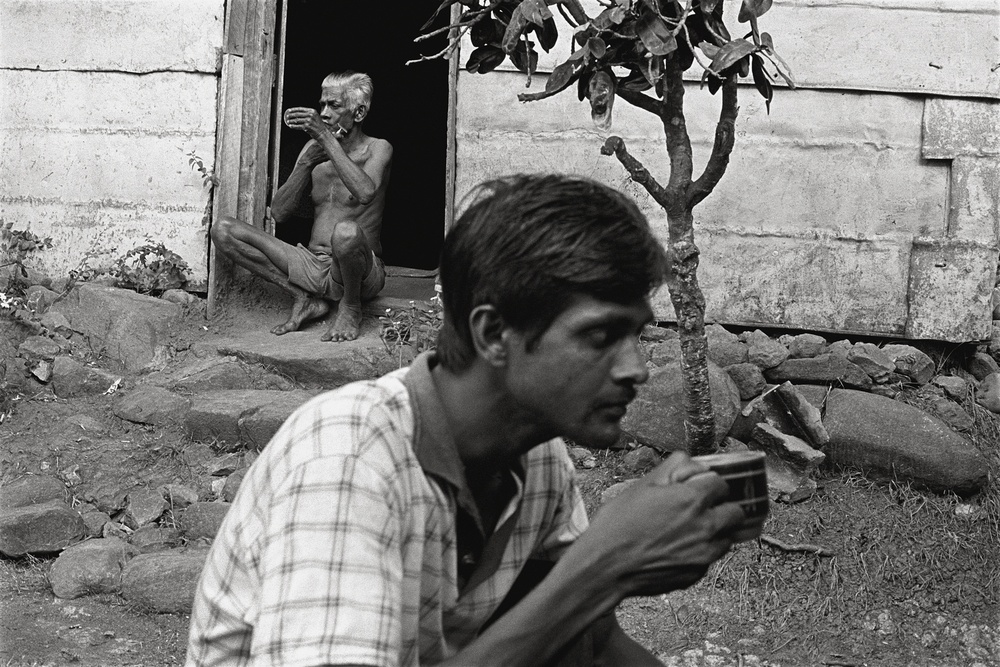

Canecutters at work in the fields, harvesting, loading cane trucks or relaxing under shades of trees all tell stories of a day in the life of a canecutter, its highs of achieving a day’s goal of a truck laden with cane, but too heavy to be pulled out of the fields, requiring manual labour to give it a push forward. Men lying bare chest on the grass with edges of the cane knife, a farmer’s hat and enamel drinking bowl showing in the photos give one a reality check on the “grounded” lifestyle in villages where people are usually one with nature. Women cooking in a communal environment, a man sipping tea from a cup with an elderly man sitting on the stone steps of his house, shaving his cheeks while looking into a small hand held mirror in the background, children glued to the TV while lying on a bed, all tell the stories of the time-held past and the modern present. The photo of the man shaving reminds me of one terrifying moment in my own childhood when I broke the only mirror my family had. It was about 2x2 cm in size with a red square frame. My dad had the most use for it as he shaved everyday. He had built a special shelf where the mirror sat as a permanent fixture in our home. He kept his shaving gear and brush on the side. All family members had to stand by the shelf whenever need arose for the mirror and that day I did the forbidden by removing the mirror from its position. When it slipped and broke, my mother wailed and slapped me on my head. Luckily, I salvaged a large broken piece which did the tricks until the next cane payment when my mother bought a new, larger mirror. Oh, how I wish I had brought my dad’s mirror with me to Australia!

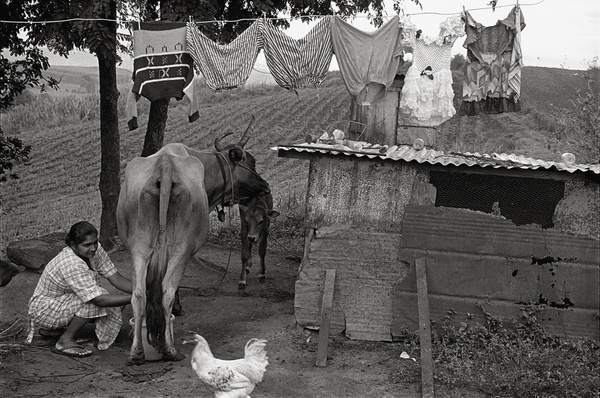

Photos of 90-year-old Sumintra Devi taking a nap, women milking cows, eating on a table decorated with a floral cloth, with a wall clock and modern kitchen gadgets lined on a shelf “dressed up” with decorative plastic sheets remind me of how my mother used to cut out old newspapers into designs and edgings to decorate the shelves where she kept her prized possessions such as drinking glass and a few dishes. She used them only when her brothers who were then studying in the US visited us. We had a small collection of enamel bowls and plates for daily use, sometimes taking turns when family members ate as there were so few for everyone to eat together. The photo of Anupa Devi, taken on August 29, 2003, a day before her wedding, opens another road in the life of the Fiji Indian journey. Many see marriage to overseas partners as a way out of the cycle of uncertainty in Fiji. This photo is followed by a whole section of coloured photos, taken by immediate families of those living in Vatiyaka, in their new homes in California, USA; Auckland, New Zealand; Honolulu, Hawaii, USA; Sydney, Australia; Vancouver, Canada and Calgary, Canada. All of these photos in overseas locations exuberate a certain degree of affluence, taken with backdrops of cars, plush sofas, shopping malls, men drinking beer while seated on what looks like leather chairs. The photo of a man in Canada, sleeping on his neatly made bed with a fan on the bedside table is in contrast to the realities for many of the photos from Vatiyaka where men take off their shirt to “cool off” after a hard day of work in the cane fields and sleep on the bare earth. This contrast has an excellent news value while telling the story of changing times.

A critique of the actual photos reveals that those taken overseas seem staged while Connew’s collection exhibits an air of naturalness and spontaneity. Indeed, all the photos in Connew’s collection reflect a story I can build on, about my own life as a Fiji Indian migrant. The common binding factor for all the photos, irrespective of place, is their connection to their roots, in Vatiyaka, Ba, Fiji. An essay by Professor Brij Lal of the Australian National University, who has become an international expert and voice on Fiji’s politics, himself a son of the land, is icing on the cake as the story resonates with thousands of Fiji Indians who are torn between two homes—motherland Fiji and adopted countries like Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the US. His story titled ‘Mr Arjun’, like the photos in Connew’s collection, takes the reader one full cycle through the highs and dips of migration and the personal loss that has taken a toll on many silent faces, especially the elderly. ‘Mr Arjun’ is Professor Lal’s paternal uncle whose life is rooted in tradition. Going to Australia to visit his son and his family for the first time, challenge him every step of the way, even with simple routines like washing himself with water, instead of using toilet paper, as this is what he was accustomed to. Without complaining he returns to Fiji, and dies a month later. Although Connew’s photos create a powerful imagery for those who are familiar with Fiji and its lifestyle, there would be a vacuum in the book without the story. The story and photos combine to present a compelling reality on Fiji and the damage toll from the coups and political unrest.

DR ASHA CHAND / 06.2008