texts

2015-01-28

The Waters of Life, September 1998

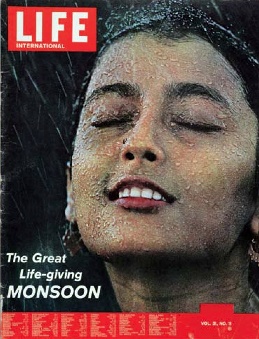

Aparna Sen, when fourteen, was the ‘monsoon girl’ in New Zealand and Magnum photographer Brian Brake’s famous 1961 photo-essay that appeared in Life, Paris Match, Queen and Epoca.

On the way to Aparna Sen’s apartment (she’s a big shot, says the hotel clerk), past the very British Victoria Memorial, past Calcutta’s zoological gardens, the horticultural gardens, and down Alipore Road, an unrelentingly congested road—as is any road or footpath in Calcutta—there stands a concrete, plastered wall about half a kilometre long, with a parapet of broken glass, rusty nails and old barbed wire. It’s an unpretentious wall, just two metres off the road, clearly visible, and protecting I’m not sure what. In the time it took to drive by, I counted eight men urinating against it. Seven hours later, on the way back, I counted five. Two days after this, off to Sen’s again, I counted three there, and four back. The waters of life. In the period between these two journeys, the Calcutta Municipal Corporation launched Operation Piddle. By the end of the first day, 155 men (no women) had been nobbled for peeing in public, and that was the count in only two of the main inner city streets.

But all the reasons she’s saying don’t come are the very reasons why I must go. She is, after all, the ’monsoon girl’.

The week before, Sen had faxed warning me not to come, Calcutta was drowning, sloshing to a halt, marooned in the worst monsoon rains since the early 70s. Just up the way, in Bangladesh, twenty-five million people were homeless. Her dentist had telephoned, cancelling her appointment saying his assistants had been unable to make it in. It was a calamity. But all the reasons she’s saying don’t come are the very reasons why I must go. She is, after all, the ‘monsoon girl’.

The sensuously virginal, and rain-spattered face of Aparna Sen, this girl on the cusp of womanhood, inclined heavenwards, became, certainly for a Western audience, the very badge of the monsoon, its evocation: the gift of fertility, romance and rapture, the waters of life - and death. Brian Brake, New Zealander, Magnum photographer, friend of Cartier-Bresson, and deceased, unexpectedly and tragically, since 1988, photographed her thirty-eight years ago, when she was fourteen, for his ubiquitous photo-essay on the monsoon, published through 1961 in Life magazine, Paris Match, Queen and Epoca; spreads that, in 1965, the Museum of Modern Art in New York included in an exhibition. Life made the photograph the cover of their international edition, and reversed it to accommodate the Life logo in the top left corner. Jawaharlal Nehru raved, wondering how Brake “got to know India so well.”

Alas, for all the cheering and foot stamping that has greeted Brake’s essay, the jeering, the inevitable jeering, hasn’t quietened down. For as long as I can remember, the sword of Damocles has hung over the portrait of Sen’s rain-spattered face, the essay’s keynote image. What were its circumstances? How did Brake do it? Did he cheat? And should we care? Apparently, people do, as if knowledge of its circumstance will provide some greater truth. Come on! Photographs have been photographers’ fictions forever: selectively framed, edited, sequenced, juxtaposed, re-structured to fit an idea; not some chronological, literal run of events, this nonsense of objectivity. That this notion continues to baffle some audiences, perplexed by the fact that even their own baggage alters the truth of an image, only suggests the insidiousness of the truth industry.

Anyway, for what it’s worth, in Sen’s words, this is how Brake did it. And you’ve got to laugh. “He took me up to the terrace, had me wear a red sari in the way a village girl does, and asked me to wear a green stud in my nose. To be helpful, I said let me wear a red one to match, and he said no—he was so decisive, rather brusque—I think a green one. It was stuck to my nose with glue, because my nose wasn’t pierced. Someone had a large watering can, and they poured water over me. It was really a very simple affair. It took maybe half an hour.”

Brake had borrowed the tomboyish Sen from the set of Samapti, her first movie, directed by Indian film demigod, Satyajit Ray, one from his trilogy, Teen Kanya (Three Daughters), based on the stories of Bengali cultural hero, Rabindranath Tagore (in 1913, he won the Nobel prize), and for release in May 1961, to celebrate the centenary of Tagore’s birth. In one year, the monsoon girl was splashed all over the US, and everywhere else Life magazine found a newsagent’s shelf (and in the 60’s that was everywhere), as well as Europe and the United Kingdom. Then, as a dazzling discovery in Ray’s movie, she had film offers gushing in from about the world. All were deflected with a flick of her mother’s Japanese fan, including one from the great man Ray himself; school, school, school.

By her mid-twenties Aparna Sen was Bengal’s most famous film star; money, money, money. Lowbrow, commercial cinema that drove her daft (the hotel clerk wanted to know why she had had her broken tooth repaired, he had fallen in love with it), and, inevitably, to writing and directing for “the kind of cinema I believe in.”

You must understand this was a well-connected family. Her father, Chidananda Das Gupta, an exceptionally bright and agreeable man (“one of my closest friends”), became Ray’s biographer, and who, with Ray, founded the Calcutta Film Society in 1947, which, after the film censorship of the British Raj, helped open the floodgates to movies from here, there, and everywhere. As a child Aparna Sen had her sensibilities shaped by Battle Potemkin, the Russian classic, flickering at night on the verandah wall, the films of Ingmar Bergman, Akira Kurosawa, and a house-guest in Jean Renoir. From Renoir’s knee, at age three, she asked, why is your face so red? Answer: “I’ve had too many chillies.”

But, back to the photograph. “I felt I was just a model, a prop. I did what I was asked to do. Nothing more, or less. This photograph, it’s amazing the way it conveys a great deal more than went into it. In a way, it’s so like Ray; Ray is the master of the close-up. In one close shot, there would be so much information, emotional and physical. The same with this photograph. The drops of water, the texture of the skin, the expression on the face, all of it. Brake said, ‘Feel the rain on your face.’ He said no more than that. You see, in India, a young girl with the first rain ... the first rain is known to be good for you, there is a tradition of getting wet in the first shower of the monsoon. After all the heat, the first shower is so welcome. And there is a beautiful smell of wet earth; you find it in a lot of literature and poetry, the smell of the earth getting wet. It’s a lovely, strange, sensual smell. And I think that sense of smell comes through in the photograph. I had no idea Brake was an important photographer, or that the photograph would come on the cover of Life. I just thought it was somebody wanting to photograph me, and creating rain, it’s a monsoon photograph, oh, very well. So I thought, what do I feel when it rains on my face? Usually, I like it. It wasn’t, oh God ... So, I just enjoyed it.”

There were two watering cans,” Sen explains. “While someone filled one, an assistant of Ray’s, standing on a chair, poured from the other.

Brake sent the magazine “to the monsoon girl”. “I thought that was so sweet. I love being called the monsoon girl. When my parents showed me the magazine, it was a bit of a surprise, and I didn’t like the way I looked. I looked more twenty-eight, than fourteen, and I was all teeth. I didn’t like myself at all. And then Bansi, Ray’s art director, he said, ‘Oh, go on, you’re not better looking than this’, so I shut up after that, of course. I now like it.” “There were two watering cans,” Sen explains. “While someone filled one, an assistant of Ray’s, standing on a chair, poured from the other.”

Then there’s the semi-autobiographical content of Paroma (1985), her second movie as writer/director. “Semi-autobiographical?” she snaps. “What gave you that idea? Paroma’s was a quest for her identity. I’ve never had any problems with mine!”

But wait a minute. A Life magazine photographer comes to India, during the monsoon, to photograph a woman, with whom he has an affair, and whose water-spattered face becomes a fullpage spread in the magazine. There is enough detail here to reel in the events of thirty-eight years ago, I would have thought.

“Oh, I see what you mean. Nobody has ever mentioned this before. You’re absolutely right. These things may be subconscious, but I was not aware of that connection until today. You see, because I have been married, divorced and remarried (and divorced and remarried again), many people think that is what Paroma is about, in fact, a film about adultery, and nothing else. The loss of identity matters very little to them. Yet, that is what interests me. It's like saying Lady Chatterley’s Lover is only about an adulterous affair with a game keeper, and not about the class system. So many people have said Paroma is autobiographical. I was reacting to that. I wanted a little more credit for my imagination. Everything is not autobiographical.”

An antique gramophone from Ray’s Samapti, turned up twenty-one years later in her first, and intensely venerated, writer/director endeavour, 36 Chowringhee Lane (1981). An unconscious reference? “Yes.” It’s how she writes her scripts too. “You see the thing is, the creative process is unconscious; it’s not an intellectual process.” 36 Chowringhee Lane began (in a hotel room, when she was miserable with acting) as a couple of pages, a short story that looked more like a screenplay. “I talked about it a lot with friends and, as I talked, the details grew. It was not as if I thought about them, and composed them in my head. My last script (August 1998), I wrote in a week ... I dictated it.”

But, back to the photograph, and Brake’s monsoon. “This is a romantic view, certainly. But, in India, the monsoon is romantic. I know it’s fraught with difficulty, but in literature, in painting, culturally, it is romantic, sensuous. A season where lovers meet, and if they can’t, there’s the pain of separation. I can’t begin to tell you how much has been written about the monsoon. Tagore has scores of songs. Other poets, too, and a great deal of Sanskrit literature. A whole lot of Rajput paintings depict the monsoon.”

I mention The Grand Trunk Road, a book by the remarkable Indian photographer, Raghubir Singh, (he lives in Paris) with its uncompromising facts of Indian life, absurdly poetic juxtapositions, the monsoon as destroyer rather than libidinous metaphor.

“That is there, too. That is a reality, too. But it doesn’t invalidate the other. Raghubir is very contemporary. Whereas Brian Brake and, particularly, Cartier-Bresson (in 1936, Cartier-Bresson appeared as a young curate in Jean Renoir’s film, A Day in the Country), were much, much earlier. Parts of India exist in the 21st century, and parts still in the 15th. So, it is very difficult to come to any conclusion quickly. Since 1980, there’s been tremendous change. India was in it’s own little world until telecommunications - Mrs Ghandi said there will be a television in every home—and now there is cable television, so many satellite channels where you get the BBC, Chinese television, Australian, French, everything under the sun.” As if to muddle any presumption, the Indian writer R.P. Gupta wrote (in 1988) that a Calcuttan street dweller of twenty-five years had never heard of Mother Teresa.

Aparna Sen’s face, at fifty-two, is a refined and elegant picture with its classical curves mimicking those of the fourteen-year-old in both Samapti and Brake’s photograph. Her face is fatter now, Sen says, but, for a moment, she tightens at the lips, and changes tack. “Why always go along with an ism?” In this instance, feminism, which, after her movies (all deal with issues concerning women), comes as something of a surprise, and must have caught off guard those feminists in India who, particularly after Paroma, saw her as a new voice. Sananda, the prosperous, middle-class, Bengali women’s magazine that Sen has edited for twelve years, since Paroma, would have doubled the surprise. “What’s wrong with cookery, what’s wrong with beauty?” Bourgeois, she was told. “You know, a lot of feminists are very silly. I’ll tell you why. Because they are always preaching to the initiated.” What they write is being read only by feminists, she reasons. “So what is that achieving? It has some archival value and some news value, but what else is it achieving?”

In the inaugural issue of Sananda, she says, gathering her sari, her lips full again, there was a debate on the label “housewife”.

In the inaugural issue of Sananda, she says, gathering her sari, her lips full again, there was a debate on the label “housewife”. “We quoted a letter from a sixty-year-old woman, and one day I want to make a film about this.” The woman wrote, saying she had married at seventeen, and had worked in the family home every day since, and now at sixty-years-old, she wants to go on a pilgrimage. “It’s not important where I go, but I want to go away by myself, and I am not being allowed to do that. Everyone says, no, you can’t go on your own. My husband says you can’t go on your own. My children say you can’t go on your own, my daughters, my sons-in-law, my grandchildren, they all say, you can’t go on your own. And I say I want to go, but I don’t have any money that’s mine.”

Sen finishes the story: “There’s no money that belongs to her, specifically. She may have a joint account with her husband, or there may be an account in her name, but she is not free to take the money.” It’s an Aparna Sen movie, no question, a plum story, and where Sen expects you to find her feminism.

She accompanies me across the building’s eighth floor landing to the lift, and apologises for having less than I had hoped for on Brian Brake. I try to reassure her. Then I shake her gentle but resolute hand, and grin all the way to the ground. What must she think (and I didn’t ask), someone coming all this way to follow up on a photograph taken so long ago? She didn’t know that Brake had died.

Back in New Zealand, on the way home from Wellington airport, I count Aparna Sen’s rainspattered face more than twenty times on Te Papa Tongarewa, Museum of New Zealand posters pasted in the streets, high, low, and all over the place. The Museum has resurrected the photo-essay as an exhibition.

BRUCE CONNEW / 10.1998