publications

1987-10-01

SOUTH AFRICA review, Art New Zealand #44, Spring 1987

A review of SOUTH AFRICA,

Riemke Ensing

Bruce Connew and Vernon Wright

Hodder & Stoughton, Auckland 1987

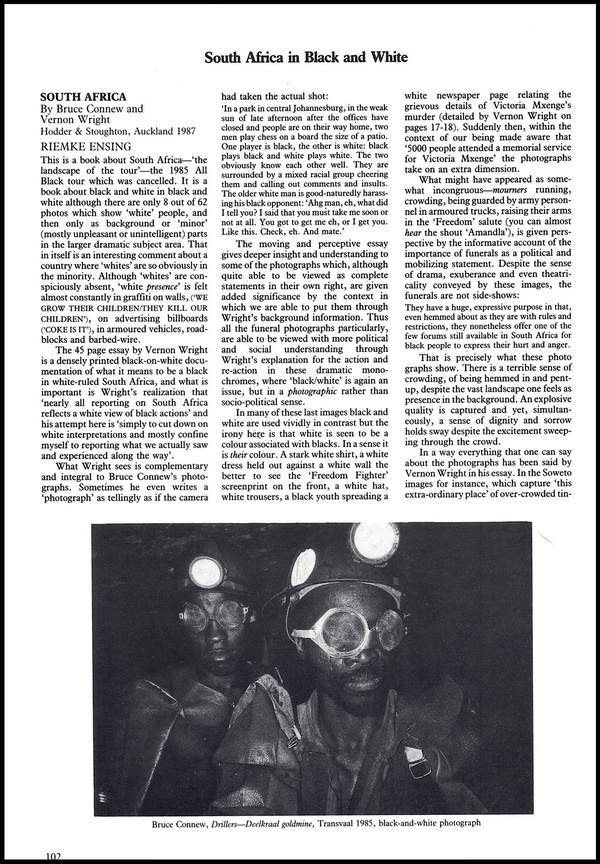

This is a book about South Africa—‘the landscape of the tour’-the 1985 All Black tour which was cancelled. It is a book about black and white in black and white although there are only 8 out of 62 photos which show ‘white’ people, and then only as background or ‘minor’ (mostly unpleasant or unintelligent) parts in the larger dramatic subject area. That in itself is an interesting comment about a country where 'whites' are so obviously in the minority. Although ‘whites’ are con-spiciously absent, ‘white presence’ is felt almost constantly in graffiti on walls, (‘WE GROW THEIR CHILDREN/THEY KILL OUR CHILDREN’), on advertising billboards (‘COKE IS IT’), in armoured vehicles, roadblocks and barbed-wire.

The 45-page essay by Vernon Wright is a densely printed black-on-white documentation of what it means to be a black in white-ruled South Africa, and what is important is Wright’s realization that ‘nearly all reporting on South Africa reflects a white view of black actions' and his attempt here is simply to cut down on white interpretations and mostly confine myself to reporting what we actually saw and experienced along the way’.

What Wright sees is complementary and integral to Bruce Connew’s photographs. Sometimes he even writes a‘photograph’ as tellingly as if the camera had taken the actual shot:

‘In a park in central Johannesburg, in the weak sun of late afternoon after the offices have closed and people are on their way home, two men play chess on a board the size of a patio. One player is black, the other is white: black plays black and white plays white. The two obviously know each other well. They are surrounded by a mixed racial group cheering them and calling out comments and insults. The older white man is good-naturedly harassing his black opponent: ‘Ahg man, eh, what did I tell you? I said that you must take me soon or not at all. You got to get me eh, or l get you. Like this. Check, eh. And mate.’

The moving and perceptive essay gives deeper insight and understanding to some of the photographs which, although quite able to be viewed as complete statements in their own right, are given added significance by the context in which we are able to put them through Wright’s background information. Thus all the funeral photographs particularly, are able to be viewed with more political and social understanding through Wright's explanation for the action and re-action in these dramatic mono-chromes, where ‘black/white’ is again an issue, but in a photographic rather than socio-political sense.

In many of these last images black and white are used vividly in contrast but the irony here is that white is seen to be a colour associated with blacks. In a sense it is their colour. A stark white shirt, a white dress held out against a white wall the better to see the ‘Freedom Fighter’ screenprint on the front, a white hat, white trousers, a black youth spreading a white newspaper page relating the grievous details of Victoria Mxenge's murder (detailed by Vernon Wright on pages 17-18). Suddenly then, within the context of our being made aware that ‘5000 people attended a memorial service for Victoria Mxenge’ the photographs take on an extra dimension.

What might have appeared as somewhat incongruous—mourners running, crowding, being guarded by army personnel in armoured trucks, raising their arms in the ‘Freedom’ salute (you can almost hear the shout ‘Amandla’), is given perspective by the informative account of the importance of funerals as a political and mobilizing statement. Despite the sense of drama, exuberance and even theatricality conveyed by these images, the funerals are not side-shows:

‘They have a huge, expressive purpose in that, even hemmed about as they are with rules and restrictions, they nonetheless offer one of the few forums still available in South Africa for black people to express their hurt and anger.’

That is precisely what these photo graphs show. There is a terrible sense of crowding, of being hemmed in and pent-up, despite the vast landscape one feels as presence in the background. An explosive quality is captured and yet, simultaneously, a sense of dignity and sorrow holds sway despite the excitement sweeping through the crowd.

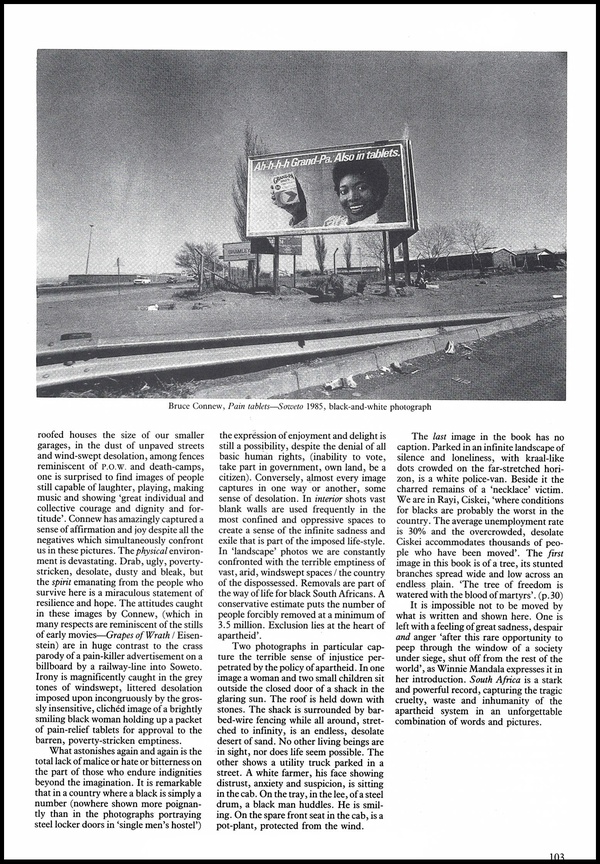

In a way everything that one can say about the photographs has been said by Vernon Wright in his essay. In the Soweto images for instance, which capture ‘this extraordinary place’ of over-crowded tin-roofed houses the size of our smaller garages, in the dust of unpaved streets and wind-swept desolation, among fences reminiscent of P.O.W. and death-camps, one is surprised to find images of people still capable of laughter, playing, making music and showing ‘great individual and collective courage and dignity and for-titude’. Connew has amazingly captured a sense of affirmation and joy despite all the negatives which simultaneously confront us in these pictures. The physical environment is devastating. Drab, ugly, poverty-stricken, desolate, dusty and bleak, but the spirit emanating from the people who survive here is a miraculous statement of resilience and hope. The attitudes caught in these images by Connew, (which in many respects are reminiscent of the stills of early movies—Grapes of Wrath / Eisenstein) are in huge contrast to the crass parody of a pain-killer advertisement on a billboard by a railway-line into Soweto. Irony is magnificently caught in the grey tones of windswept, littered desolation imposed upon incongruously by the grossly insensitive, clichéd image of a brightly smiling black woman holding up a packet of pain-relief tablets for approval to the barren, poverty-stricken emptiness.

What astonishes again and again is the total lack of malice or hate or bitterness on the part of those who endure indignities beyond the imagination. It is remarkable that in a country where a black is simply a number (nowhere shown more poignantly than in the photographs portraying steel locker doors in ‘single men’s hostel’) the expression of enjoyment and delight is still a possibility, despite the denial of all basic human rights, (inability to vote, take part in government, own land, be a citizen). Conversely, almost every image captures in one way or another, some sense of desolation. In interior shots vast blank walls are used frequently in the most confined and oppressive spaces to create a sense of infinite sadness and exile that is part of the imposed life-style. In ‘landscape’ photos we are confronted with the terrible emptiness of vast, arid, windswept spaces / the country of the dispossessed. Removals are part of the way of life for black South Africans. ‘A conservative estimate puts the number of people forcibly removed at a minimum of 3.5 million. Exclusion lies at the heart of apartheid’.

Two photographs in particular capture the terrible sense of injustice perpetrated by the policy of apartheid. In one image a woman and two small children sit outside the closed door of a shack in the glaring sun. The roof is held down with stones. The shack is surrounded by bed-wire fencing while all around, stretched to infinity, is an endless, desolate desert of sand. No other living beings are in sight, nor does life seem possible. The other shows a utility truck parked in a street. A white farmer, his face showing distrust, anxiety and suspicion, is sitting in the cab. On the tray, in the lee, of a steel drum, a black man huddles. He is smiling. On the spare front seat in the cab, is a pot-plant, protected from the wind.

The last image in the book has no caption. Parked in an infinite landscape of silence and loneliness, with kraal-like dots crowded on the far-stretched horizon, is a white police-van. beside it the charred remains of a ‘necklace’ victim. We are in Rayi, Ciskei, ‘where conditions for blacks are probably the worst in the country. The average unemployment rate is 30% and the overcrowded, desolate Ciskei accommodates thousands of people who have been moved’. The first image in this book is of a tree, its stunted branches spread wide and low across an endless plain. ‘The tree of freedom is watered with the blood of martyrs’. (p.30)

It is impossible not to be moved by what is written and shown here. One is left with a feeling of great sadness, despair and anger ‘after this rare opportunity to peep through the window of a society under seige, shut off from the rest of the world’, as Winnie Mandala expresses it in her introduction. South Africa is a stark and powerful record, capturing the tragic cruelty, waste and inhumanity of the apartheid system in an unforgettable combination of words and pictures.

RIEMKE ENSING / 10.1987