publications

2014-10-06

Street wise, ART NEWS NZ, Winter 2003

“ART NEWS NZ looks at three photographers who have worked in a documentary style. Their work is strongly narrative and sometimes highly politicised.”

Street Wise

IN AN ARTICLE about Fiona Clark’s exhibition ‘Go Girl’, published in ‘Art New Zealand’, Peter Wells comments that “the art world, for all its commitment to originality, is as narrow in its adherence to fashion as the average suburban hairdresser”.

Ironically, though we might laugh at the accuracy of his observation, Clark explains that in gay parlance the term “hairdresser” refers to a gay man. Many male hairdressers are in fact gay, she says.

Clark’s groundbreaking photographs, taken when she was 20, document the gay, lesbian and trans gender scene in Auckland City in the 1970s. In 1975 two of her photos of transvestites dancing were included in a major photographic survey, ‘The Active Eye’, touring the country. The photos, from her series ‘Dance Party’, caused an orgy of moral outrage and a media typhoon. In the name of “decency”, the mayor of New Plymouth stripped Clark’s images from the show when it appeared at the Govett Brewster. By the time it reached the Auckland City Art Gallery, the exhibition was cancelled. That it caused such a furore—the biggest controversy in New Zealand’s photographic history—is a measure perhaps of how attitudes have changed. Or have they?

Clark plans to tour ‘Go Girl’, which includes the original 1970s series and recent photographs and videos of some of the surviving subjects, but she has received no public gallery support. The show will open in Sydney at Mori Gallery on 14 June.

It took Clark five years to get ‘Go Girl’ up and running and the show opened at the Govett Brewster late last year. This was the first time the 1970s photographs had all been seen together. There was a moving powhiri, in which the kaumatua reclaimed the subjects of Clark’s photos, many of whom have died since the photos were taken.

Fittingly, transsexual Member of Parliament, Georgina Beyer, opened the exhibition and wrote a testimonial to assist Clark in touring the show: “Fiona’s perspective on this subject is raw, glamorous, upfront and does not attempt to avoid the reality of the lives of its subjects.

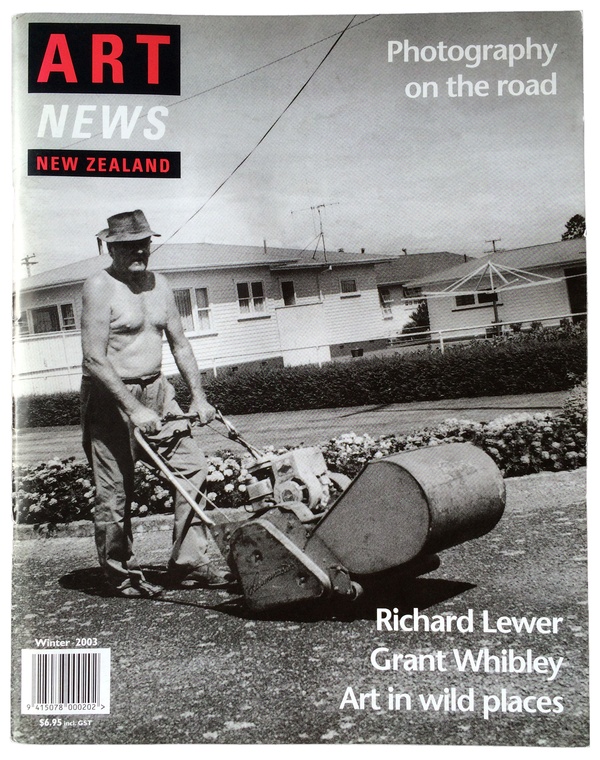

PETER BLACK’S ‘Real Fiction’, a survey show of photographs taken over the last 30 years, was curated by Greg O’Brien for City Gallery, Wellington, and will travel around the country.

In the exhibition title Black acknowledges the murky line between reality and fiction in his photographs, his interest in unravelling photography’s conundrum—the fact that on one hand the camera never lies and on the other, it always lies.

“One idea of post modernism is that there’s no reality left in the world—everything is either media driven or can be changed by the viewer—I think that’s true. We’ve learned over the years that everything is a construct. Certainly I was playing with these ideas with the composite photos, which include 32 photos in each frame.”

Born in Christchurch in 1948, Black belongs to an illustrious generation of photographers – Laurence Aberhart, Fiona Clark, Bruce Connew, Bruce Foster, Anne Noble and Peter Peryer. He studied photography at Wellington Polytechnic, freelanced during the late 1970s and, in 1982, showed ‘Fifty Photographs’ at the National Art Gallery—the first solo exhibition by a contemporary New Zealand photographer to be held by that institution.

Much of Black’s work is shot in black and white and has a narrative element. He prefers black and white because of its dreamlike quality and the element of nostalgia people associate with it. For him black and white photos speak more directly to the subconscious than colour.

“There’s a longing or a recognition associated with black and white photos. I’ve heard it said that we dream in black and white,” he says.

In his photographs ordinary moments in daily life appear surreal, prompting us to look again in order to figure out what is going on. He sees the world as a ready-made vehicle for image making and is always pushing his art in new directions. Though his interests remain similar, his working methods vary greatly between each project.

“I use different methods to get results. There’s no point in carrying something on and just being good at it. Some people expect a certain type of photo from me but they have to get used to the idea that it will always be slightly different.”

The 1980s series, ‘Moving Pictures’, for instance, was shot from a moving vehicle and details a ropy utopia of people waiting at bus stops, sheep by the side of the road, and barns in the countryside. Scrawled across the sides of these buildings are the words “Twiggy needs grubbing” and “Oblivion”.

Text on street signs, models in shop windows, and other people’s artworks, often feature in his photographs—the amateurish street sign on a wall in Petone, which says: “Always getting better”. With his typical playful and reflexive approach Black photographed that because he thought, “it was time I got better at what I was doing.”

Each series of photographs takes about two years to complete and Black likes to work in series so he can put photos together in a sequence.

“I’m a storyteller and I’m using photography. All the stories, all the sequences and all the bodies of work have a beginning, a middle and an end.”

One subject often provides impetus for the next.

“Quite often I stumble across something on a proof sheet and it leads me on to another body of work. I don’t take that many photos—I find it difficult to take photos that interest me; I’m hardly ever satisfied.”

In one series he shot photographs from the hip, giving up control so he would be surprised.

“You actually get a lot of good photos that way—it might appear that I would take more photos and just wait for chance or serendipity to give me a good result, but it wasn’t like that. I got more good photos using that method than I did by using the camera on a tripod. I found it surprising.”

Unlike Clark, who always identifies the subject and the date in her captions, Black’s photographs of people are less specific.

“I’m very careful with captions not to give people’s names. It’s not really meant to be a portrait of them. Some photographers, like Richard Avedon, note down the name and the time of day. My photographs are more like self-portraits—I’m not trying to say this is actually how the people are. They are only that way in that split second. I’m not trying to say I know them or that it’s a true story about them.” Street photography is the hardest thing he’s done.

“You have to be ready to react and looking very, very hard—harder than you would ever do normally. And looking hard and concentrating hard is the most tiring thing I’ve ever done in my life. You spend just a couple of hours on the street looking that hard and feeling that much, and being aware of so much – your body can’t actually take it. Your mind is working overtime and you walk home and you’re drained. Not many people do that kind of photography because it’s the hardest way of getting good photographs. It’s hard to know what you want; it’s hard being amongst the flux of everything going on; and it’s hard physically and mentally. There are much easier ways of taking photographs and getting better results than that.”

Will he continue to do it? “I think I will because I just see things that are so wonderful and nobody else is doing it—I just feel someone should be. It hurts me when I walk past something and I don’t have my camera. I might see three wonderful women standing talking, and the light is so beautiful; they look wonderful. Maybe they’re in their best clothes because they’ve come to town. If I haven’t got my camera and I don’t take it, I feel a little twinge—I’ve missed it, it’s never going to be like that again. It’s not going to be like that the next second when I look back. It’s only like that for one split second—they’re going to move slightly, the light is going to change, anything could happen. And I feel a twinge of regret.”

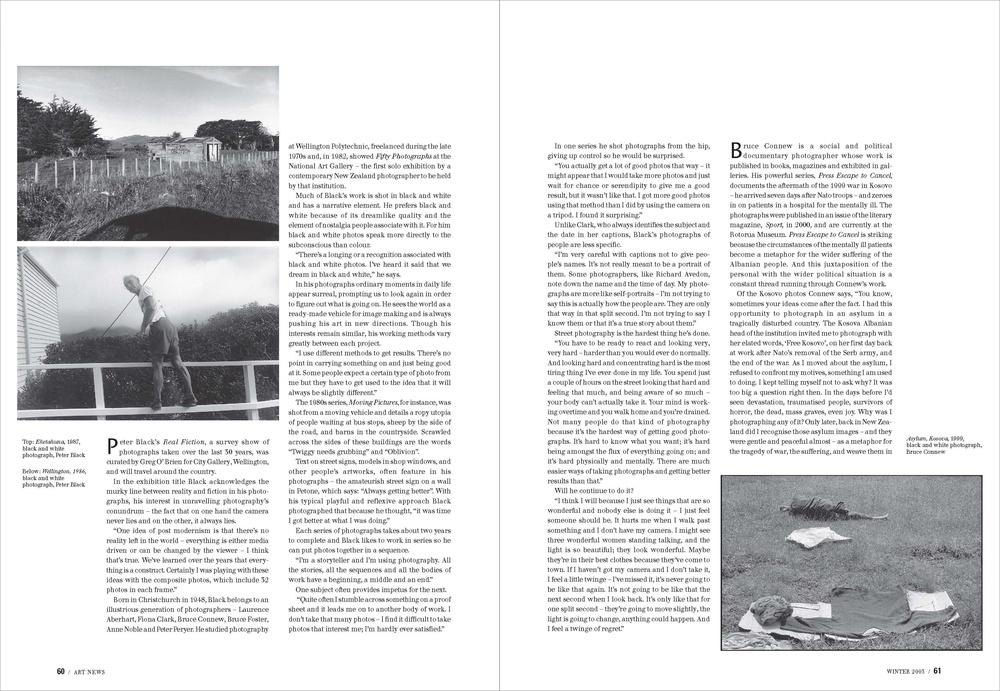

BRUCE CONNEW is a social and political documentary photographer whose work is published in books, magazines and exhibited in galleries. His powerful series, ‘Press Escape to Cancel’, documents the aftermath of the 1999 war in Kosovo—he arrived seven days after Nato troops—and zeroes in on patients in a hospital for the mentally ill. The photographs were published in an issue of the literary magazine, ‘Sport’, in 2000, and are currently at the Rotorua Museum. ‘Press Escape to Cancel’ is striking because the circumstances of the mentally ill patients become a metaphor for the wider suffering of the Albanian people. And this juxtaposition of the personal with the wider political situation is a constant thread running through Connew’s work.

Of the Kosovo photos Connew says, “You know, sometimes your ideas come after the fact. I had this opportunity to photograph in an asylum in a tragically disturbed country. The Kosovar Albanian head of the institution invited me to photograph with her elated words, ‘Free Kosova’, on her first day back at work after Nato’s removal of the Serb army, and the end of the war. As I moved about the asylum, I refused to confront my motives, something I am used to doing. I kept telling myself not to ask why? It was too big a question right then. In the days before I’d seen devastation, traumatised people, survivors of horror, the dead, mass graves, even joy. Why was I photographing any of it? Only later, back in New Zealand did I recognise those asylum images—and they were gentle and peaceful almost—as a metaphor for the tragedy of war, the suffering, and weave them in and out of the others I had taken through that time.”

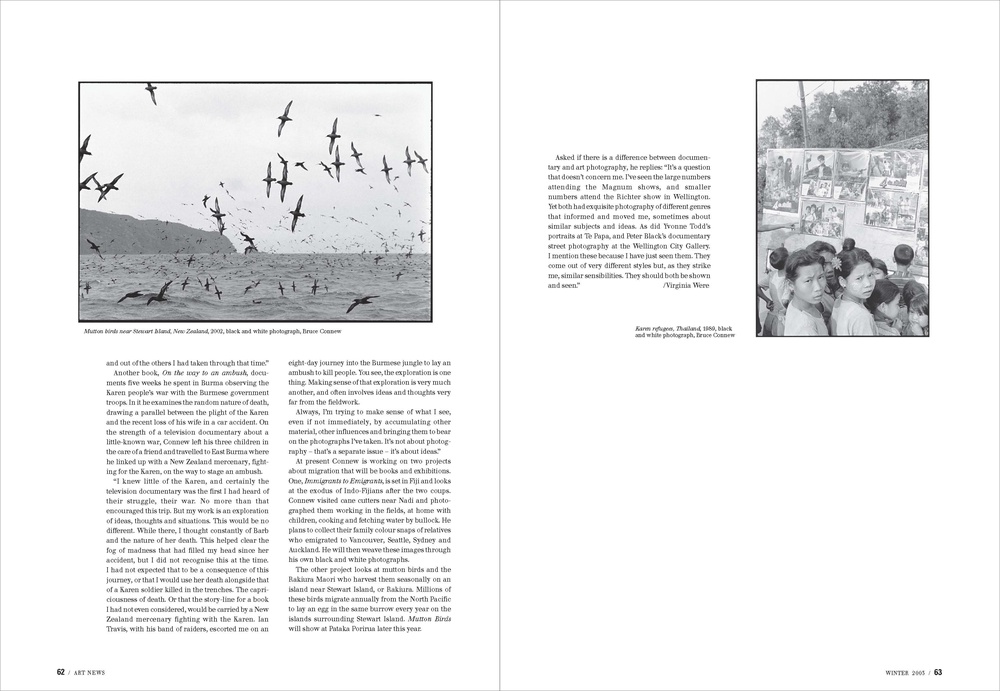

Another book, ‘On the way to an ambush’, documents five weeks he spent in Burma observing the Karen people’s war with the Burmese government troops. In it he examines the random nature of death, drawing a parallel between the plight of the Karen and the recent loss of his wife in a car accident. On the strength of a television documentary about a little-known war, Connew left his three children in the care of a friend and travelled to East Burma where he linked up with a New Zealand mercenary, fighting for the Karen, on the way to stage an ambush.

“I knew little of the Karen, and certainly the television documentary was the first I had heard of their struggle, their war. No more than that encouraged this trip. But my work is an exploration of ideas, thoughts and situations. This would be no different. While there, I thought constantly of Barb and the nature of her death. This helped clear the fog of madness that had filled my head since her accident, but I did not recognise this at the time. I had not expected that to be a consequence of this journey, or that I would use her death alongside that of a Karen soldier killed in the trenches. The capriciousness of death. Or that the story-line for a book I had not even considered, would be carried by a New Zealand mercenary fighting with the Karen. Ian Travis, with his band of raiders, escorted me on an eight-day journey into the Burmese jungle to lay an ambush to kill people. You see, the exploration is one thing. Making sense of that exploration is very much another, and often involves ideas and thoughts very far from the fieldwork.

Always, I’m trying to make sense of what I see, even if not immediately, by accumulating other material, other influences and bringing them to bear on the photographs I’ve taken. It’s not about photography—that’s a separate issue—it’s about ideas.”

At present Connew is working on two projects about migration that will be books and exhibitions. One, ‘Immigrants to Emigrants’ [‘Stopover’, 2007), is set in Fiji and looks at the exodus of Indo-Fijians after the two coups. Connew visited cane cutters near Nadi and photographed them working in the fields, at home with children, cooking and fetching water by bullock. He plans to collect their family colour snaps of relatives who emigrated to Vancouver, Seattle, Sydney and Auckland. He will then weave these images through his own black and white photographs.

The other project looks at muttonbirds and the Rakiura Maori who harvest them seasonally on an island near Stewart Island, or Rakiura. Millions of these birds migrate annually from the North Pacific to lay an egg in the same burrow every year on the islands surrounding Stewart Island. ‘Mutton Birds’ [‘Muttonbirds—part of a story’, 2004] will show at Pataka Porirua later this year.

Asked if there is a difference between documentary and art photography, he replies: “It’s a question that doesn’t concern me. I’ve seen the large numbers attending the Magnum shows, and smaller numbers attend the Richter show in Wellington. Yet both had exquisite photography of different genres that informed and moved me, sometimes about similar subjects and ideas. As did Yvonne Todd’s portraits at Te Papa, and Peter Black’s documentary street photography at the Wellington City Gallery. I mention these because I have just seen them. They come out of very different styles but, as they strike me, similar sensibilities. They should both be shown and seen.”

VIRGINIA WERE / 06.2003

“One of the measures of a civil society is when its minorities are included in the mainstream of arts, culture and heritage. I believe this exhibition contributes to this ideal,” she wrote.

Growing up as a lesbian in the macho culture of 1960s Inglewood wasn’t easy for Clark and when she moved to Auckland and then enrolled in Elam to study sculpture in 1972, her life really began. Her job at the Ca’Dora café, an all night coffee house in Queen Street, added to her new sense of belonging.

It was a time of ferment. Socially and politically things were swinging; Albert Park was a hangout for hippies and Vietnam protesters, marijuana was being smoked and Gay Lib was emerging—men were stashing women’s clothes in their bags and venturing out for an evening in drag. They couldn’t actually walk the streets in drag, says Clark, for fear of being harassed by the police or beaten up by the public.

As well as being arresting images, Clark’s photographs function as historical documents. They show us how some things have changed and some haven’t. The images, for instance, were originally eight by ten colour photos printed by Clark at Elam because if she sent them to a commercial lab they probably would have been stolen or destroyed. Now they are lavish 700mm by 1m digital Lambda prints.

And bravery within art institutions?

“I still think there is not enough bravery in New Zealand photography—people still dance around the edge politely. Part of me wanting to show the work was to say: ‘Just jump in there and do it; you’ve got to leave the circle of comfort.’”

This could well be Clark’s mantra as a photographer and it certainly applies to the people she has photographed with compassion and intelligence.

Clark comments, “It was a significant time for a lot of people because they were growing up. It was telling to find that though people had very few possessions, they had kept the photos. They all knew the photos were good, we just had to convince other people and that took a while. It’s a very slippery history, that people don’t acknowledge—and we don’t have that visual history.”

“The theatre restaurants in New Zealand changed our night life. But we don’t know who it was. Was it in Karangahape Road? Of course it was. And who were the people doing it? They were drag queens and kings. So people know these stories but they don’t have a space for any of that history.”

In a radio interview Kim Hill asked Clark a blunt question: “Are you a good photographer or are you a photographer who happened to be in the right place at the right time when nobody else was?”

Clark replied: “I am a good photographer.”

She then explained what makes a good photographer: “Because the work has lasted… It doesn’t matter if the image was from 1975—it’s still a beautiful image, it still works, it will still draw you to it.”

Apart from the gutsy, glamorous beauty of the images, one of the things that engages is their intimacy—the result of Clark’s ability to engage and gain the trust of her subjects. This is a strong feature of all her work—she takes an insider’s approach rather than looking in from the outside. And by doing this she tells her own story, taking photographs that are to some extent self-portraits.

Clark is primed to tell the stories of people living outside the mainstream. She has photographed people living with Aids, and documented her own experience of injury caused by a serious car accident.

Now she is organising a national tour for ‘Go Girl’and documenting the events surrounding Steven Wallace’s murder—she insists it was a murder—in Waitara, where she lives.