reviews

2014-08-27

Muttonbirds—part of a story in TIME, Pacific edition, 21 November 2005

As City Gallery Wellington curator Gregory O’Brien has put it, “he is a particularly astute observer of the act of breaking open the surface of the earth.”

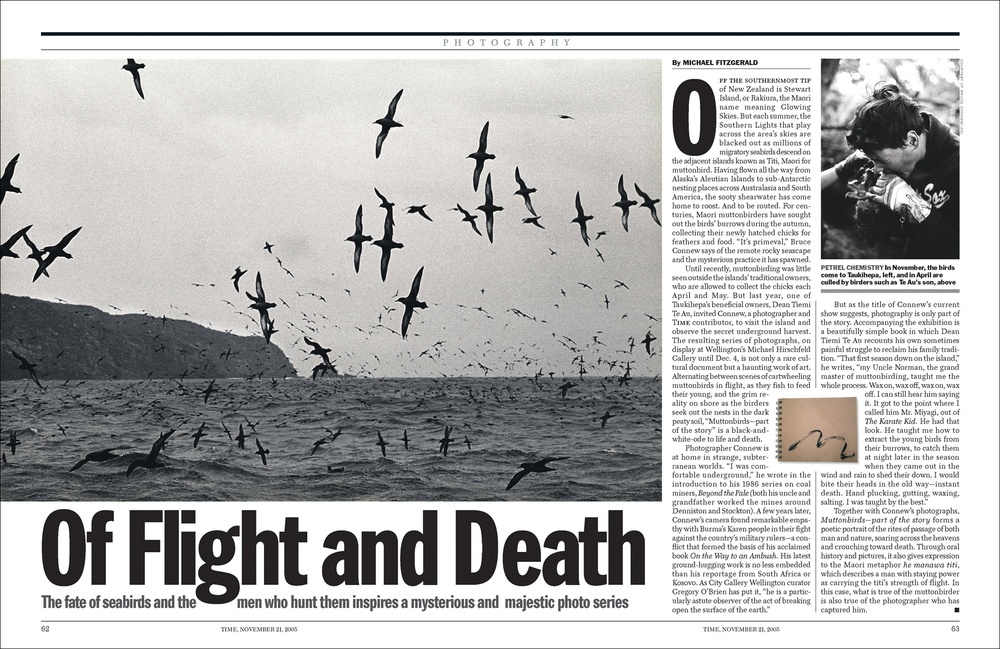

Off the southernmost tip of New Zealand is Stewart Island, or Rakiura, the Maori name meaning Glowing Skies. But each summer, the Southern Lights that play across the area’s skies are blacked out as millions of migratory seabirds descend on the adjacent islands known as Titi, Maori for muttonbird. Having flown all the way from Alaska’s Aleutian Islands to sub-Antarctic nesting places across Australasia and South America, the sooty shearwater has come home to roost. And to be routed.

For centuries, Maori muttonbirders have sought out the birds’ burrows during the autumn, collecting their newly hatched chicks for feathers and food. “It’s primeval,” Bruce Connew says of the remote rocky seascape and the mysterious practice it has spawned.

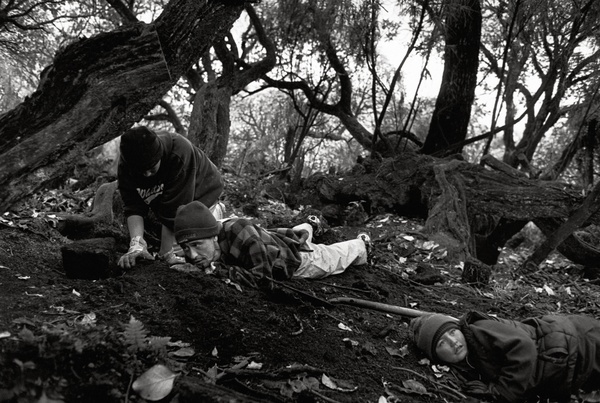

Until recently, muttonbirding was little seen outside the islands’ traditional owners, who are allowed to collect the chicks each April and May. But last year, one of Taukihepa’s beneficial owners, Dean Tiemi Te Au, invited Connew, a photographer and Time contributor, to visit the island and observe the secret underground harvest. The resulting series of photographs, on display at Wellington’s Michael Hirschfeld Gallery until Dec. 4, is not only a rare cultural document but a haunting work of art. Alternating between scenes of cartwheeling muttonbirds in flight, as they fish to feed their young, and the grim reality on shore as the birders seek out the nests in the dark peaty soil, ‘Muttonbirds—part of the story’ is a black-and-white ode to life and death.

Photographer Connew is at home in strange, subterranean worlds. “I was comfortable underground,” he wrote in the introduction to his 1986 series on coal miners, ‘Beyond the Pale’ (both his uncle and grandfather worked the mines around Denniston and Stockton). A few years later, Connew’s camera found remarkable empathy with Burma’s Karen people in their fight against the country’s military rulers—a conflict that formed the basis of his acclaimed book ‘On the way to an ambush’. His latest ground-hugging work is no less embedded than his reportage from South Africa or Kosovo. As City Gallery Wellington curator Gregory O’Brien has put it, “he is a particularly astute observer of the act of breaking open the surface of the earth.”

Together with Connew’s photographs, ‘Muttonbirds—part of a story’ forms a poetic portrait of the rites of passage of both man and nature, soaring across the heavens and crouching toward death.

But as the title of Connew’s current show suggests, photography is only part of the story. Accompanying the exhibition is a beautifully simple book in which Dean Tiemi Te Au recounts his own sometimes painful struggle to reclaim his family tradition. “That first season down on the island,” he writes, “my Uncle Norman, the grand master of muttonbirding, taught me the whole process. Wax on, wax off, wax on, wax off. I can still hear him saying it. It got to the point where I called him Mr. Miyagi, out of The Karate Kid. He had that look. He taught me how to extract the young birds from their burrows, to catch them at night later in the season when they came out in the wind and rain to shed their down. I would bite their heads in the old way—instant death. Hand plucking, gutting, waxing, salting. I was taught by the best.”

Together with Connew’s photographs, ‘Muttonbirds—part of a story’ forms a poetic portrait of the rites of passage of both man and nature, soaring across the heavens and crouching toward death. Through oral history and pictures, it also gives expression to the Maori metaphor he manawa titi, which describes a man with staying power as carrying the titi’s strength of flight. In this case, what is true of the muttonbirder is also true of the photographer who has captured him.

MICHAEL FITZGERALD / 11.2005