reviews

2014-08-27

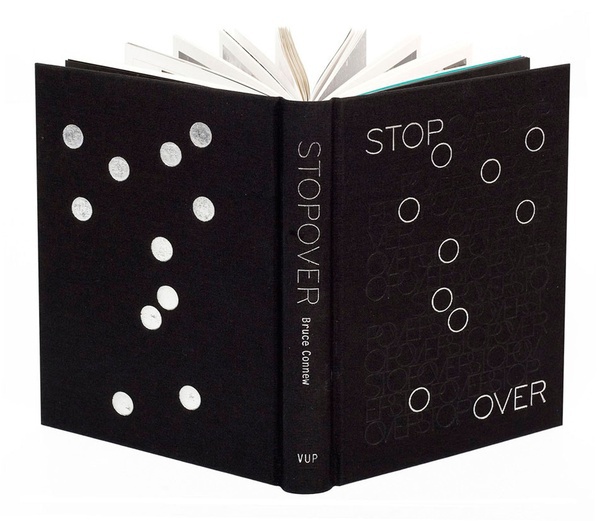

‘Stopover’, TIME, Pacific edition, 24 September 2007

Only one ethnic Indian has become Prime Minister of Fiji. He was promptly deposed.

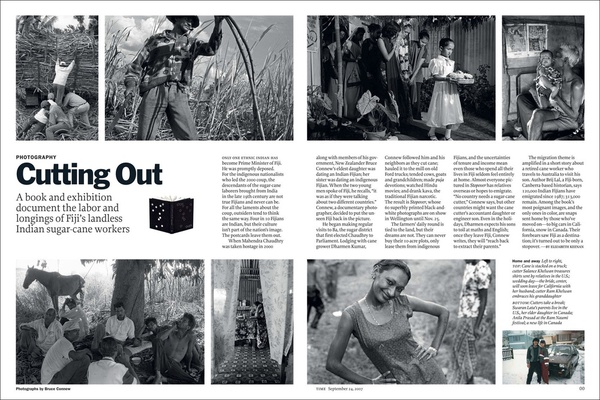

ONLY ONE ETHNIC INDIAN HAS become Prime Minister of Fiji. He was promptly deposed. For the indigenous nationalists who led the 2000 coup, the descendants of the sugar-cane laborers brought from India in the late 19th century are not true Fijians and never can be. For all the laments about the coup, outsiders tend to think the same way.

Four in 10 Fijians are Indian, but their culture isn’t part of the nation’s image. The postcards leave them out.

When Mahendra Chaudhry was taken hostage in 2000 along with members of his government, New Zealander Bruce Connew’s eldest daughter was dating an Indian-Fijian; her sister was dating an indigenous Fijian. When the two young men spoke of Fiji, he recalls, “it was as if they were talking about two different countries.” Connew, a documentary photographer, decided to put the unseen Fiji back in the picture.

He began making regular visits to Ba, the sugar district that first elected Chaudhry to Parliament. Lodging with cane grower Dharmen Kumar, Connew followed him and his neighbors as they cut cane; hauled it to the mill on old Ford trucks; tended cows, goats and grandchildren; made puja devotions; watched Hindu movies; and drank kava, the traditional Fijian narcotic. The result is Stopover, whose 60 superbly printed black-and-white photographs are on show in Wellington until Nov. 25.

Almost everyone pictured in ‘Stopover’ has relatives overseas or hopes to emigrate.

The farmers’ daily round is tied to the land, but their dreams are not. They can never buy their 10-acre plots, only lease them from indigenous Fijians, and the uncertainties of tenure and income mean even those who spend all their lives in Fiji seldom feel entirely at home. Almost everyone pictured in Stopover has relatives overseas or hopes to emigrate. “No country needs a sugar-cane cutter,” Connew says, but other countries might want the cane cutter’s accountant daughter or engineer son. Even in the holidays, Dharmen expects his sons to toil at maths and English; once they leave Fiji, Connew writes, they will “reach back to extract their parents.”

The migration theme is amplified in a short story about a retired cane worker who travels to Australia to visit his son. Author Brij Lal, a Fiji-born, Canberra-based historian, says 120,000 Indian Fijians have emigrated since 1987; 313,000 remain. Among the book’s most poignant images, and the only ones in color, are snaps sent home by those who’ve moved on—to big cars in California, snow in Canada. Their forebears saw Fiji as a destination; it’s turned out to be only a stopover.

ELIZABETH KEENAN / 09.2007