reviews

2021-04-26

‘A Vocabulary’ review, Ewan Morris

... ‘A Vocabulary’ review by historian, Ewan Morris, PastWord, 26 April 2021

Bruce Connew, A Vocabulary

Yesterday was Anzac Day, and across Aotearoa New Zealand, people gathered to commemorate at memorials to New Zealand’s involvement in overseas wars. Many other memorials across the country, however, were created to remember the wars that took place within Aotearoa between Māori and the forces of the settler state in the nineteenth century. In a recent exhibition and book, the photographer Bruce Connew focuses his camera and our attention on these other war memorials.

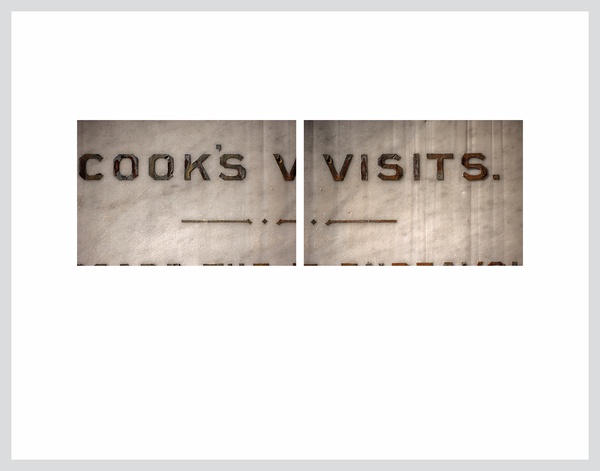

The photographs in the book start with monuments to the period before, and around the time of, the Treaty of Waitangi. An early image simply reads ‘Cook’s visits’ (2)*, subverting the valorisation of Captain Cook (and its mirror image, demonisation) by reducing him to the level of a relatively fleeting visitor. Instead of picturing a glorious ‘discoverer’, the viewer might think instead of a hapless tourist on a ‘Cook’s tour’ (‘a rapid tour of many places’).

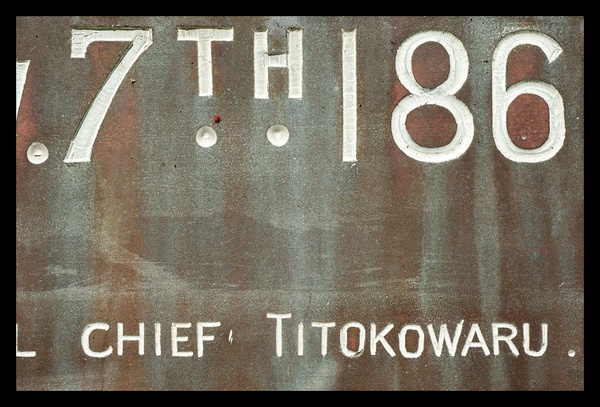

The bulk of the book, however, deals with memorials to the New Zealand Wars, mostly (but not exclusively) erected by and to Pākehā. Here, in panel after panel, the rhetoric of Empire is laid out. Māori defending their land are ‘rebels’ who commit ‘murder’. Pākehā soldiers are ‘brave men’ who ‘fell gallantly’, and it is they, not Māori, who are described as fighting for ‘their country’ or for ‘New Zealand’. British and colonial troops have their names, ranks and regiments recorded, while their opponents mostly appear as undifferentiated ‘Maori tribes’.

There is another perspective in the book, however, undercutting the homogenisation of Māori in the photographed memorials. Each image has a caption which provides information not only about the memorial itself, but also about those who took part on both sides in the battle the memorial commemorates. Here, just as Pākehā troops have their commanders and regiments listed, so too Māori (whether fighting alongside or against British and colonial forces) are given the dignity of having their rangatira and iwi named.

Some memorial inscriptions appear in full, or close to it, but the most thought-provoking are the carefully-selected fragments of text. At times these are almost perversely fragmentary. I’ve described the memorial in Whanganui to Te Keepa Te Rangihiwinui as ‘New Zealand’s wordiest memorial’, but Connew’s photographs (e.g. 280-281) show only a few words from the detailed accounts of battles that appear on bronze panels near the base of the monument . An image from another memorial (88) seems to be part of an obscure mathematical puzzle: ‘L 27th 24 ½ Y’.

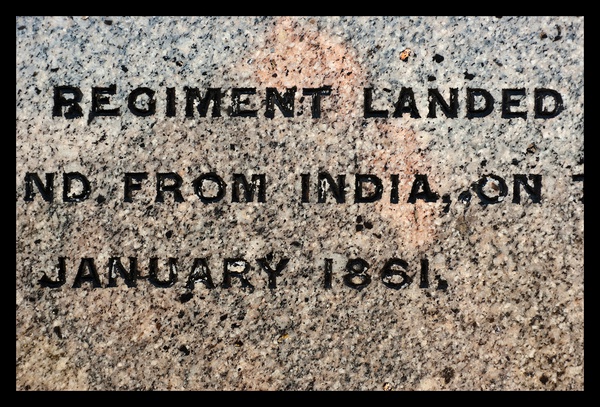

Some images remind us that Māori were at war with a global empire: ‘Empress of India’ (4); ‘regiment landed from India’ (76); ‘Crimean War’ (151). Others highlight hazards other than enemy fire: ‘accidentally shot by a comrade’ (23); ‘lost at sea’ (84), ‘all drowned’ (218).

The words Connew has focused on can also make us think about memory itself. We can read the words ‘who lost’ (187) and add a question mark, asking ourselves who were the winners and losers of these battles, and of the wars as a whole. Words from another memorial have been arranged to read ‘Maori War were not known’ (152). We could interpret this as suggesting that too few New Zealanders have known about the history of the New Zealand Wars, or that Pākehā have not understood Māori perspectives on those wars.

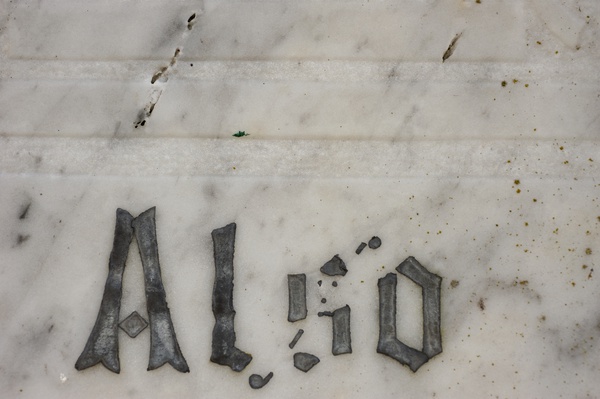

One image consists only of ‘&’ (39), while two others read simply ‘Also’ (165, 244). These suggestions of some other words about to follow could make us think about the words and stories that are absent from these memorials. Like most war memorials, they largely ignore the impact of war on non-combatants, including soldiers’ families, so it is striking when the memorialised men are placed in the context of a family: ‘also his wife’ (139); ‘somebodys sons’ (221). Above all, the impact of the wars on Māori, the loss of lives, livelihoods and land, is nowhere to be found in most of these texts.

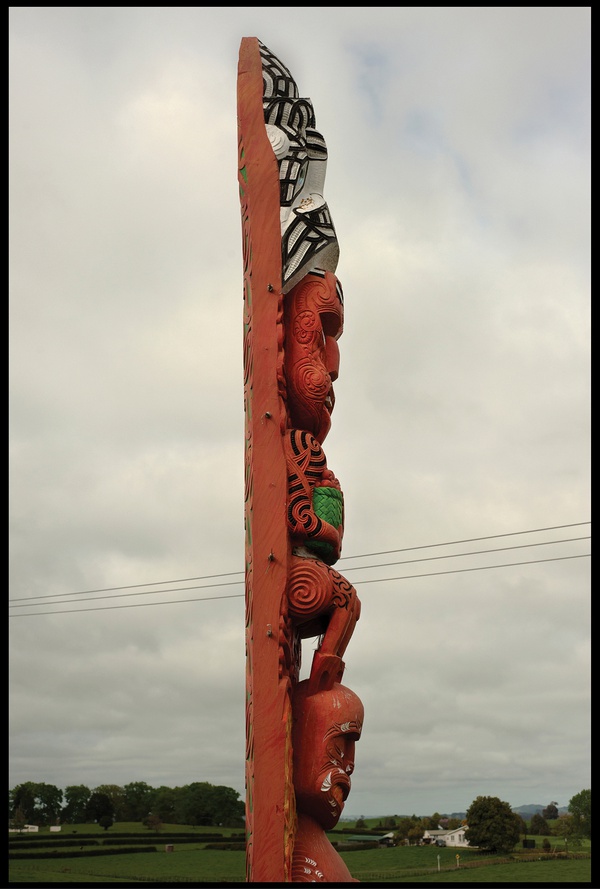

Perhaps in an effort to provide some balance to the overwhelmingly Pākehā narratives presented on the colonial memorials, Connew includes a few photographs of pou whakamaumahara (commemorative poles) erected by Māori at battle sites in recent years. While the increasing use of pou whakamaumahara to commemorate the New Zealand Wars is an interesting and important development, I’m not convinced it was the right decision to include them here. The strength of Connew’s project is its focus on text. All the other images in the book focus exclusively on the memorials’ inscriptions: there are no photos of statues, crosses or other sculptural elements that appear on some of these monuments. Certainly, whakairo (Māori carving) has its own vocabulary, but so does Pākehā sculpture. Including pictures of Māori commemorative sculpture in an otherwise text-focused project risks stereotyping Māori as people of the image and Pākehā as people of the word, a dichotomy that oversimplifies both cultures.

Instead of including the pou whakamaumahara, it would have been better to have included more of the texts of newer memorials that present Māori views of the wars. A few of these are included in the book: the memorial at Te Tarata (205), for example, which pulls no punches in its use of words like ‘tragically’, ‘slaughtered’ and ‘confiscation’; or the bilingual Ruakituri memorial (268), with a Māori text that tells a sharply different story from that in the English version. Even some older memorials can tell a Māori story: I would have liked Connew to have photographed the panel in Māori on the memorial to Te Keepa Te Rangihiwinui, which was written by Te Keepa’s sister and sets out their whakapapa.

The text on most of the memorials in these photographs is remarkably clear, and they generally seem to have been photographed in good light. In some cases, however, shadows and marks of age obscure the words. In two pictures of the memorial to Sir Donald McLean (51, 212), a shadow creeps across the stone, as though to suggest the way in which the reputations of men like McLean, once held up as Pākehā heroes, have become shadowed by their roles in the dispossession of Māori.

Jock Phillips, in his history of New Zealand war memorials, refers to memorials to the New Zealand Wars as ‘an essay in Pākehā-Māori relationships’. Connew’s A Vocabulary has remixed and rewritten that essay, helping us to see these memorial texts with fresh eyes. Having visited many of these memorials, I can say that most are unlovely creations, their blandness belying the brutality of war and confiscation. Yet somehow, Connew has made them appear both strangely beautiful, and beautifully strange.

*Bracketed numbers refer to image numbers in the book.

References

Bruce Connew, A Vocabulary, Vapour Momenta Books, 2021.

‘Māori Monument or Pākehā Propaganda? The Memorial to Keepa Te Rangihiwinui, Whanganui’, in Annabel Cooper, Lachy Paterson and Angela Wanhalla (eds), The Lives of Colonial Objects, Dunedin, Otago University Press, 2015, pp. 230-235.

Jock Phillips, To the Memory: New Zealand’s War Memorials, Nelson, Potton and Burton, 2016, ch. 1.

EWAN MORRIS / 04.2021