texts

2014-09-01

EDIT #45, Michael Fitzgerald, 2008

“Part sinister, part seductive, these pictures slake our thirst for seeing the workings of the world, and ourselves, in all their grainy unguardedness. With Connew’s photography, the act of looking is part of a larger unraveling—of turning life inside out and slowly bringing it into complex focus.”

UNGUARDED MOMENTS:

the photographs of Bruce Connew

CONNEW IS RARELY occupied by leisure. Coalminers, pot black-camouflaged guerrillas, muttonmbirders and Indian-Fijian sugar cane cutters—all have come into the orbit of this New Zealand documentary photographer’s ever-alert gaze. Appropriately, we were brought together through work—in Apia for a TIME magazine assignment in 2005. Our quarry was a Samoan fa’afafine nightclub performer called ‘Blondie’, and given the island languorous atmosphere, the urge to exoticize the Polynesian practice of boys raised as girls seemed irresistible. Connew did the opposite, stripping Blondie back to her daily tasks of tending to her travel agency, caring for extended family or aiga, and playing bingo each Saturday night to raise money for her local church. Blondie emerged three-dimensionally from Connew’s fly-on-the-wall photography, asking to be defined by her actions rather than the rudiments of biology. The term ‘working it’ might carry connotations of ‘Blow Up’-style fashion photography, but for Connew it is a way of bringing his subjects into focus by pushing through to an unguarded moment of truth.

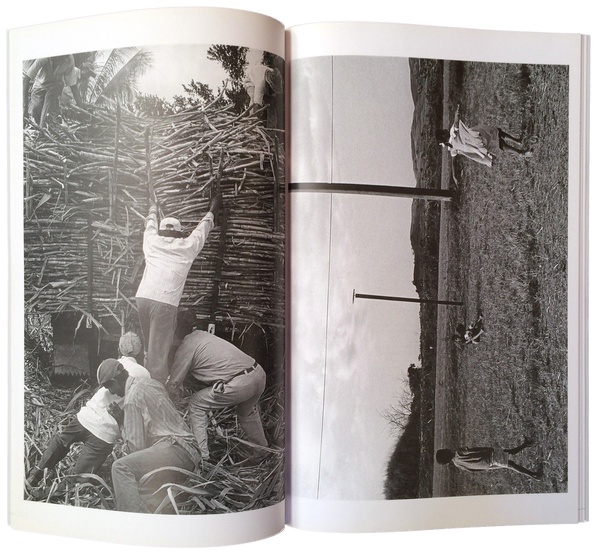

For much of this decade Connew has focussed on the Indian-Fijian sugar cane cutters of Vatiyaka, a valley settlement in the west of Fiji’s biggest island of Viti Levu. The resulting exhibition and book ‘Stopover’ (University of Hawai’i Press and Victoria University Press) makes visible the secret history of this ethnic minority who came to the South Pacific as indentured labourers in 1879. But as much as documenting a certain place in time, ‘Stopover’ makes manifest the notion of displacement. Forbidden from owning land their 10-acre plots by Fiji’s indigenous majority, the sugar cane harvesting gangs Connew photographs are but uncertain shadows across the landscape, their rights to citizenship made tenuous by a succession of coups that have gripped the country since 1987. ‘Stopover’ traces their subsequent diaspora to such cities as Sydney, Vancouver and Auckland, and asks the question, What defines a population as belonging to this patch of earth rather than that? Across seven visits to Vatiyaka, Connew searches for what fixes them to Fiji, and what, ultimately sets them free.

There is, of course, faith—predominately Hinduism—and Connew quietly observes their communal ceremonies of feasting, cleansing and calls to prayer. Most of all there’s work. Through the sugar cane fields’ successive sowing, harvesting and burning, Connew’s beautiful black and white prints enact a different kind of ritual or rite of passage—a stripping back or scarification of the landscape that seeks home through the sometimes Sisyphus-like feat of labour. There is also the haunting sense that a deeper belonging—at least in this forgotten valley—eludes them. Connew never labours the point: in late afternoon, an old man reaches to close his window shutter; on the edge of a field, a girl breaks away to hold out her arms, antenna-like, in the wind; a young bride, bound for married life in California, waits pensively for her groom. With a novelists eye, Connew hints at larger social forces that carry along these lives as if in a current, and which the sugar cane fields of Vatiyaka can’t possibly hope to contain. As ‘Mr Arjun’, a story by Fijian historian Brij V. Lal which accompanies the book, eloquently puts it, these are frequent flyer families: ‘A hundred years ago, our forbears had arrived in Fiji, ordinary folk from rural India, shouldering their little bundles and leaving for some place they had not heard of before but keen to make a new start. A hundred years later, the children and grandchildren are on the move again: the same insecurity, the same anxiety about their fate.’

With any series by Bruce Connew, the photographs are only part of the story. Just as ‘Stopover’ explores a wider narrative of cross-generational Pacific migration, so his previous book and exhibition photographed Maori muttonbirding as a stepping-off point to examine more personal issues of self-discovery and identity. In ‘Muttonbirds—part of the story’ (Vapour Moneta Books, 2004), Connew followed a former gang member of the infamous Mongrel Mob as he sought to re-establish his whakapapa or genealogy, and his custodial right to collect sooty shearwater chicks each April and May off the southernmost tip of New Zealand. subtly and seamlessly, Connew parallel’s the life and death quest of the mutton bird as it nests on Taukihepa’s dark peaty soils, with that of Dean Tiemi Te Au and his two sons, who are trained to bite the heads of the young birds as they are pulled from their burrows. Primeval life lessons are played out here, mortality writ large, with the swarming dark skies contrasted against the boys’ more meditative subterranean searchings.

In 1989, Connew found an even more unlikely and personal identification with his subject matter when he travelled to Burma to document the 40-year struggle of the Karen people, an ethnic minority seeking autonomy from Rangoon—a ‘rag-tag army in jandals’ Connew writes in the resulting book ‘On the way to an ambush’ (Victoria University Press, 1999), ‘fighting from the trenches in the hills of Burma’s eastern border region.’ Evading land mines and near-death from malaria in this forgotten war in the jungle, Connew somehow finds himself. The photographer’s skillful wrestling with the claustrophobia of trench warfare echoes his own dark reckoning following the death of Barbara, the mother of his first three children, in a car accident two years previously. Faced with the killing of a Karen comrade, struck in the back by a rocket while fetching water from a river, Connew reaches epiphany: ‘At that moment—and I accepted it was for me alone—these two quite separate deaths entwined.’ At this point, we realise, Connew’s photographs are much more than random shots taken in an unknown war, but the playing out of an intensely-felt personal quest. As former editor of the influential British photography Magazine ‘Creative Camera’ , the late Peter Turner noted of Ambush: ‘Bruce Connew’s book is at once about being witness to human beastliness, being a photographer, and being Bruce Connew.’

The same couldn’t be said of his latest series of work, ‘I Saw You’ (Vapour Momenta Books, 2007)—or so it would seem at first glance. The backdrop here is neither war nor heavy industry or a culturally-contested site, but a carpark near Connew’s former Wellington home, which the photographer stalked with long lens through the veil of double-glazing for 12 months. Having based a photographic career on negotiating the diplomatic dropping of people’s guards, it’s fascinating to watch Connew move, unmediated, through the blurred lives of these nameless subjects. The resulting jewel-like miniatures, exhibited at Wellington’s Mary Newton Gallery through July and August 2007, are both private moments in public spaces, and heat-seeking devices measuring the degrees of personal exposure, as well as the emotional curtains we put up to protect our hooded identity. These are scenes of surveillance—a girl adjusts her swimming costume, a middle-aged couple kiss, a young man appears to urinate in the bushes—prettified by the pastels of impressionism.

Even in leisure, Connew would seem to say, we are working. As are these ever-active images which, in the end, are as much about the camera’s ‘I’ as ‘You’, ultimately turning their gaze on the photographer himself: What exactly are his motives? Who or what is he searching for? Part sinister, part seductive, these pictures slake our thirst for seeing the workings of the world, and ourselves, in all their grainy unguardedness. With Connew’s photography, the act of looking is part of a larger unraveling—of turning life inside out and slowly bringing it into complex focus.

MICHAEL FITZGERALD / 04.2008