texts

2014-09-19

The Waiting War, Vernon Wright, January 1985

New Zealand’s nearest neighbour, the French colony of New Caledonia, is in a state of unrest . . . New Zealand Listener magazine

THE WAITING WAR

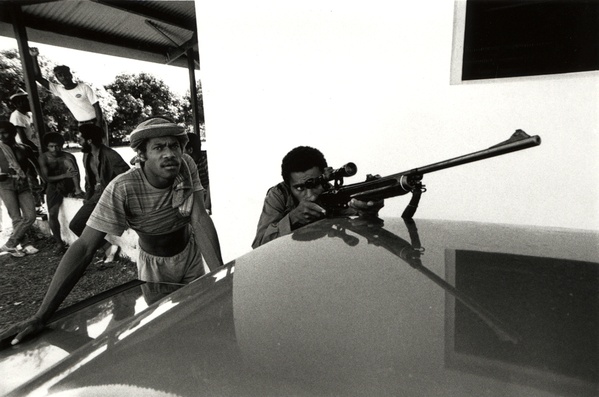

THE MAN sitting on the shady verandah shields his eyes with one hand and with the other points to a nearby ridge. Another man dressed in shorts, a camouflage jacket and a wide headband knotted on one side with the ends falling down to his shoulders, picks up a rifle and peers through the telescopic sight. He grunts an affirmation:

“Caldoches.”

“How many?”

“Three. At least three. Maybe more.”

It is a potentially serious situation. If the figures far away on the ridge are indeed caldoches (New Caledonians of French descent), and if they are armed—and it is assumed they will be— then their target will almost certainly be these Melanesians now looking up at them.

It is puzzling, however. Even though the figures are close on five kilometres away they must know they will be spotted on up on a ridge. And even though this is not exactly a war—not yet—people are still being killed, and if you are carrying weapons with murderous intent you don’t expose yourself to your target, who is also armed, without a very good reason.So what are they up to?

If they are armed caldoches then in a way they represent the biggest threat of all to these members of the Kanak Socialist Liberation Front (FLNKS) watching them, bigger even than the French, who of course have the firepower to obliterate anyone they care to, and who for that reason, and because of international opinion, do not use it. But vigilantes are different. Motivated by a belief in their rights, as indeed are these Kanaks, they are prepared to use random violence.

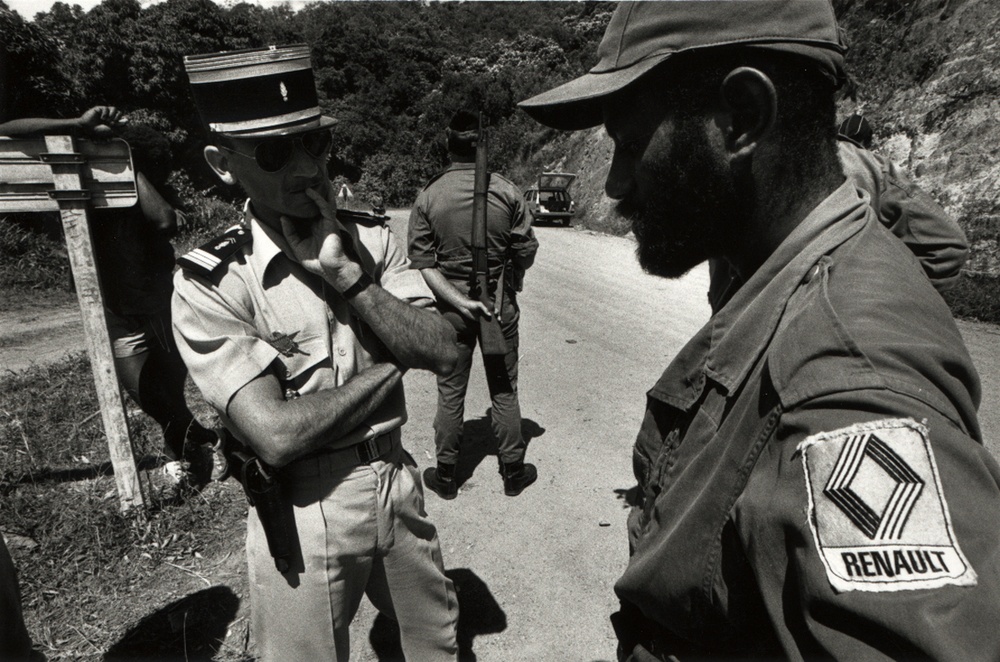

The second roadblock is a major social event. Not only are their French soldiers checking cars for weapons and liquor, but there are also Kanaks of the FLNKS checking on the French checkers, making sure they do their job properly.

THE DANGER posed by vigilantes is one reason the FLNKS maintain roadblocks in this area, around the town of Thio on the east coast of New Caledonia, some 126 kilometres away from Noumea.

The roadblocks or checkpoints on the road to Thio have a kind of logic about them which, as with all things political in this country, is extraordinarily complex. There are three major roadblocks. The first and outermost is manned by French soldiers. They wish to know who travellers are, where they are going, and why. Since they are travelling into a “Kanak-held” area the car must be searched for liquor, because liquor is now forbidden outside of Noumea. In “native” areas. But two bottles of wine in the food box do not qualify as liquor, naturellement!

The second roadblock is a major social event. Not only are their French soldiers checking cars for weapons and liquor, but there are also Kanaks of the FLNKS checking on the French checkers, making sure they do their job properly. Their fear is that the French might turn a blind eye to caldoches taking their “personal” weapons into the area. They also want to make sure the Kanak travellers do not get too hard a time from these metropolitan French troops.

One Kanak stands on a high bluff overlooking the roadblock, shouting instructions and comments to his friends on the road, who are armed with sticks and grubbers in contrast to the machine pistols of the French. He also has a walkie-talkie to alert Kanaks at the third roadblock which cars they shouls stop and check again.

There is a constant, half-bantering dialogue between the two groups of checkers. The Kanaks remark that it is not possible for them to get work outside the tribe. A gendarme complains that if the Kanaks throw him out and back to France they will not be able to play petanque together.

And there is a third group here—a group of two reporters and three photographers from a Paris-based news agency. They’ve been here for a fortnight or so, cruising the roadblocks between Noumea and Thio, waiting (hoping?) for trouble. And they have little doubt as to where they are.

“Est-ce que vous etes venus de France?”

“Ici c’est la France ... nous venons de la metropole.”

(“Have you come from France?” “This is France ... we are from the mainland.”)

It is very hot. The heat rises from the road and a thin layer of dust settles on the sweaty brows of these actors. It is 32 C and relative humidity is around 75 per cent. Occasionally a truck carrying household possessions of a caldoches or colon (settler) family passes through on its way to Noumea, the family evacuating while it can, and reminding the checkers and observers at the roadblocks of the seriousness of the situation.

There is a third checkpoint a few kilometres before Thio, an impromptu one set up by Kanaks—just to make sure. Production of a pass issued by the FLNKS office in Noumea is enough to persuade the sniper lying hidden in the bushes just off the road to lower his rifle.

The French gardes mobiles recently found seven rifles in the car of the caldoches mayor of Thio, and reported their find to the FLNKS. To that extent both the troops and Kanaks, although on different sides of the fence, have a shared goal in attempting to stop or reduce the violence. For all that, the French troops do not take kindly to FLNKS rifles either, so when a French troop-carrier roars into view at this roadblock the marksman and his friends take to their heels.

THIS “pas d’armes” is carried on and around Thio itself. About 200 members of the gardes mobiles are stationed in the town and from their barracks they run routine patrols in an armoured personnel carrier. Not that there is much need to. Thio is all but deserted by the caldoche and colon families that lived there, most of them associated in some way with the nickel mining industry which form 99 per cent of the value of New Caledonia’s exports. Out on the road past the private tennis courts and the closed stores inviting Diners Club and American Express lies the hostel of the Societe Le Nickel, which more than any other building represents the desertion of Thio. Outside sit two abandoned vehicles, a Peugeot and a Land-Rover; upstairs the ropes sag on the amateur boxing club’s ring, head guards and gloves lie in the dust and a leaking tap has flooded the washroom.

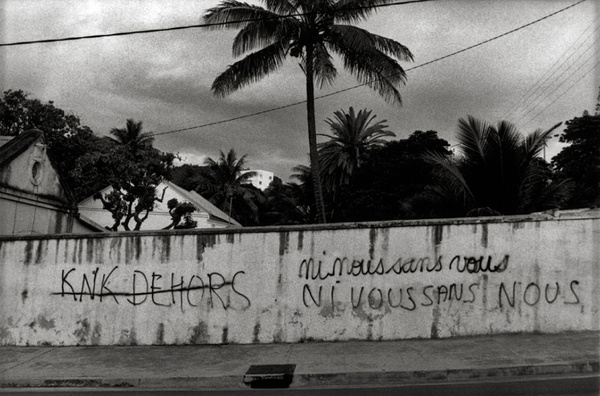

While French soldiers patrol the empty streets of Thio, the area around the town is in the hands of the FLNKS. The traveller must go through Kanak barricades to both enter and leave the area, which has been “reclaimed” by Kanaks from caldoches and colons and from the French state. Land is at the centre of the problems in New Caledonia: it is a symbol of the oppression that Melanesians have been subjected to under French rule, and the reclaiming and repossession of land, sometimes violently but more often with harassment and implied violence, is a reclaiming of sovereignty.

Kanaks, under various political groupings, the most recent of which is the FLNKS, have reoccupied a good deal of land in the adjoining districts of Canala and Thio, and the occupations around Thio are regarded as particularly important because it is the key to an area containing one third of the world’s known reserves of nickel.

Thus, while the Kanaks have dismantled barricades and roadblocks elsewhere in the country as a gesture of reconciliation during the negotiations for settlement being carried out by the French High Commissioner, Edgard Pisani, they will not abandon the occupations around Thio. That is their beachhead. If Pisani’s negotiations should fail and conflict develop more openly as a result, it is in Thio that trouble can most obviously be expected.

TO THE WATCHERS at the FLNKS headquarters on the outskirts of Thio, therefore, the appearance of a group of apparently armed people on a ridge overlooking their headquarters is an event to be taken seriously.

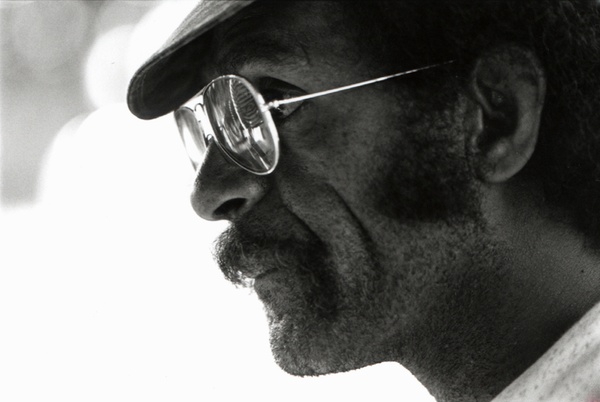

The Kanak leader at Thio is Eloi Machoro, an engaging, slightly self-conscious and angry former school teacher. Every revolution, it seems, throws up a “bad boy” for the international press, and as far as the conservative press of France is concerned, Eloi Machoro is it. It was Machoro whose photograph was splashed around the world as he put an axe through a ballot box in Canal a few months ago; it was Machoro, who, with another Kanak leader, made a highly publicised visit to Libya, although they would not say whether it was to seek support for the independence cause.

It was Machoro who succeeded Pierre Declercq as secretary-general of the moderate pro-independence Union Caledonienne when Declercq was killed in 1981*, and who declared in a speech in Canala at the time: “The reconquest of of New Caledonia will begin here. When we have cleaned up this area we will move on to Thio, La Foa and Boulapari. Each tribe must draw up a list of those [caldoche and colon] they want to leave. This is going to be a trial of strength. Everyone should know that we are prepared to use guns if necessary.” He has been as good as his word, and remarkably successful.

(*Declercq's death is generally, though not wholly, regarded as a political murder, and he is now thought of as the first “white martyr” of the independence movement. His death can be seen as a direct cause of the hardening of attitudes among those seeking independence.)

Machoro jumps into a (“liberated”) car and is driven off at high speed to try and survey the occupied ridge from the other side. His method of operation, he explains, is to approach a farmer, whether colon or caldoche, and attempt to persuade him to turn in his farm to the land office which, under recent land-reform legislation, would compensate the farmer and turn the land over to the Kanaks. (The Kankas would still not own the land, merely caretake it for the French state.) If the farmer agrees, and also wants to stay in the area, then the Kanaks are, says Machoro, happy for them to work together. Better that, he says, than for the farmer to have to leave with only his underpants!

“The problem is that with most of the colons, when we talked to them like that, they got out their rifles. But not all, not all. Just near here the tribe’s chief has a friend with whom they made an agreement. The colon went to see the land office, he kept a small piece of land for himself and sold the rest to the land office for the tribal chief. And he’s there at the present moment.

“The others nearby played tough—they got out their rifles, and now they’re no longer here.” Machoro points vaguely north. There’s one there called Bulle, and there’s another, called Santa Cross, he’s one of the really tough ones. We don’t see anymore of Bulle, he’s possibly in the village if he hasn’t taken his stuff and gone off to Noumea.

“The other—Santa Cross—that’s his vehicle there, the blue Toyota. We seized it, and we saw him crying on television, saying that he’s going to collect his things and leave. Lafleur (Jacques Lafleur, leader of the anti-independence RPCR) has asked him to stay and defend New Caledonia, but he says, ‘I’ve lost everything. What should I defend here? I’m leaving for France because I’ve got nothing left.’

“There’s another, at the bottom of the valley, called Lacrosse. Now Lacrosse and his sons refused the Kanak demands, and his cattle were chased and killed. Now he patrols his land with his horse and rifle, and when he sees Kanaks he fires at them. There’s a young Kanak up there they call Mbalto’s. Why Mbalto? Because Mbalto’s the name of a racehorse in Noumea who runs well, and the sons of Lacrosse called him Mbalto because each time they saw him and fired at him he ran like Mbalto. But now Lacrosse’s sons have taken off, gone, and when he wants to kill his cattle now he goes and ask the people of the tribe, because the people of the tribe have said to him, ‘You’re not to kill any more cattle, they’re ours’. So it is finished.”

A few kilometres down the road the northern side of the ridge becomes visible, the car stops, Machoro and his driver meet up with others and examine the terrain through a telescope to decide the best route. The Kanaks are expecting an attack by local caldoche militia. This might be it, so there strategy is to get the caldoches first. Small groups of men set out, armed with a motley collection of mostly shotguns and smallbore hunting rifles, advancing up different spurs in a pincer movement to the top of the ridge.

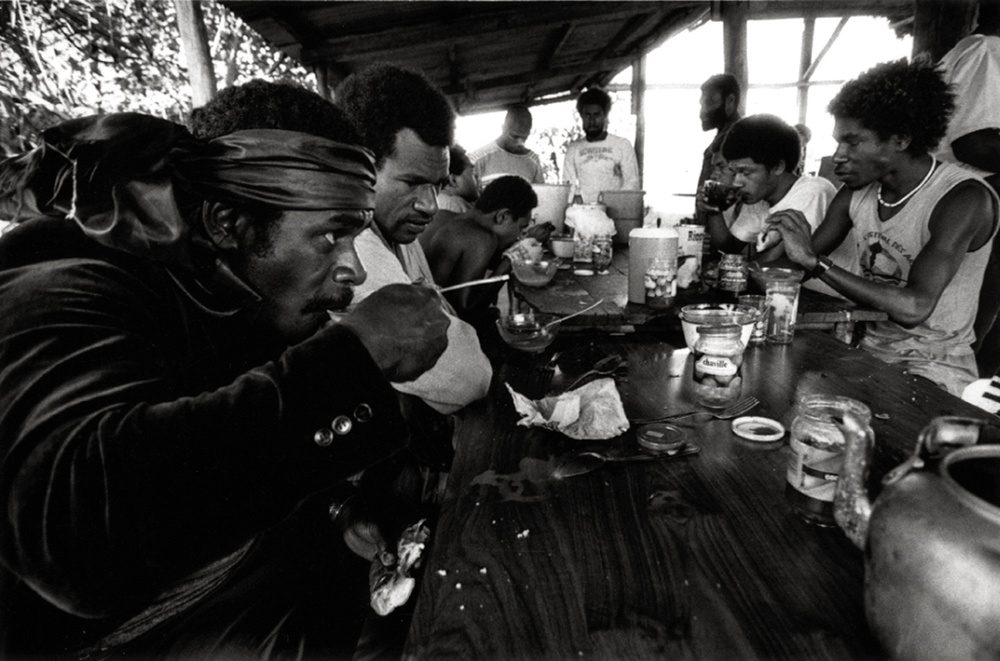

The FLNKS headquarters at Thio is manned on a rotation basis by about 60 Kanaks at a time. Most of them come from the Canala district to spend a week on duty in Thio, then they return home for two weeks before beginning their next tour of duty. The 60 divide into four teams to cover four different checkpoints, each tean spending six hours on six hours off.

The checkpoints watch for arms, liquor and “undesirable people”. Such people are let through, but usually only for very short periods. And who qualifies as undesirable? They are colon and “people responsible for economic control of the area—big business people who exploit the people of the area”. One who qualifies is M. Galliot, mayor of Thio and head of the extreme right-wing National Front. Like all right-wing people, according to the Kanaks, M. Galliot “had his own little militia”.

While some men climb the ridges and other man the checkpoints, the rest sprawl in the shade under mango trees. Women, who help on the barricades from time to time, tend the open-fire cooking area and prepare the next meal. It is a marae-like environment but with unmistakable French influence. Some sit with a bowl of cafe au lait and munch on a stick of bread, occasionally decorating the bread with pale French butter and rhubarb jam imported from from Paris. Others sit and read with interest an article on their activities in the magazine ‘Paris-Match’, all the more interested because they have never seen a journalist from ‘Paris-Match’ in the area.

It is a long waiting game now. The figures on the ridge turn out to be members of the gardes mobiles taking a new commander of the garrison at Thio on a tour of the area. The Kanak insurgents are for the moment, says Machoro, playing dead. They have given Edgard Pisani the two months he asked for, until late February, to come up with a solution, and in the meantime the function of the checkpoints is to stop trouble before it starts, and to hold on to the gains that have been made.

Whatever comes of Pisani‘s initiatives, for these people, here and now, there is no alternative to sovereign independence.

VERNON WRIGHT / 01.1985

(As this edition of the New Zealand Listener magazine was going to press news came through that Kanak leader Eloi Machoro and his lieutenant Marcel Nonaro had been killed in an exchange of shots with gendarmes.)