texts

2014-08-26

‘Muttonbirds—part of a story’, Dean Tiemi Te Au, 2004

“It’s a beautiful place, Taukihepa, without all the politics, sitting down there at the bottom of New Zealand with its muttonbirds and early histories.”

She arranged a meeting in a cafe. Dean brought along his young daughter, Kahutatara, who remained a picture of patience for two hours while he took me through his crumpled Maori Land Court succession order, line by line, and talked at length about Taukihepa, a muttonbird island just off the south-west coast of Stewart Island, and a birding area there he called Heretatua. We talked too about the muttonbirds’ long haul from near the Arctic Circle to burrows in the dark, peat soils of the muttonbird islands. Females lay one egg in the same burrow every year, he told me, which I thought astonishing, given the distance of their journey. He also said they were hopeless at landing, crashing through the canopy and thumping to the ground. He stood up and held his arms out like wings and gently shook his narrow frame to show me how the birds recovered for several minutes before waddling off to their burrows. He said over twenty million of them arrived in New Zealand each year. Much of this was very new to me. He explained that his entry to muttonbirding had not been straightforward, but that’s his story to tell.

To prove that you are a descendant, the regulations say, you must present your whakapapa to the Maori Land Court. It turns out that not everyone has. What follows is part of an elaborate and sometimes unfortunate story.

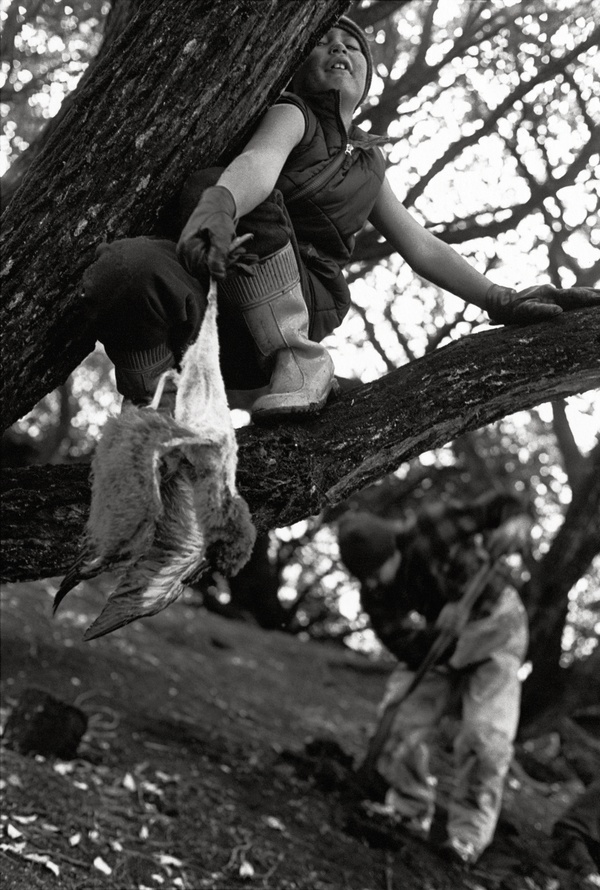

For six days in November two years back, Dean and I, along with a couple of friends to help cover launch costs, motored around some of the muttonbird islands and up to Preservation Inlet in search of the vast flocks of muttonbirds fishing at sea that Dean had described. Along with numerous smaller groups, we came across two flocks numbering tens, if not hundreds of thousands of muttonbirds. Each time, the spectacle was out of this world. The following year Dean invited me to Taukihepa to photograph him and two of his sons, Dean and younger brother Tiemi, muttonbirding on Heretatua. They had been on the island two weeks when I arrived with Catherine, my wife. Our stay was brief. It turned out, according to The Titi (Muttonbird) Regulations 1978, that we should not have been there and Dean was prosecuted by the Department of Conservation and recently fined $100. According to the same regulations, which are administered by the Department of Conservation, to go muttonbirding on beneficial islands you must be a descendant of the original owners of Stewart Island. To prove that you are a descendant, the regulations say, you must present your whakapapa to the Maori Land Court. It turns out that not everyone has. What follows is part of an elaborate and sometimes unfortunate story.

The following oral history is the text for ‘Muttonbirds—part of a story’. It is from a series of interviews in 2003 by Bruce Connew with Dean Tiemi Te Au.

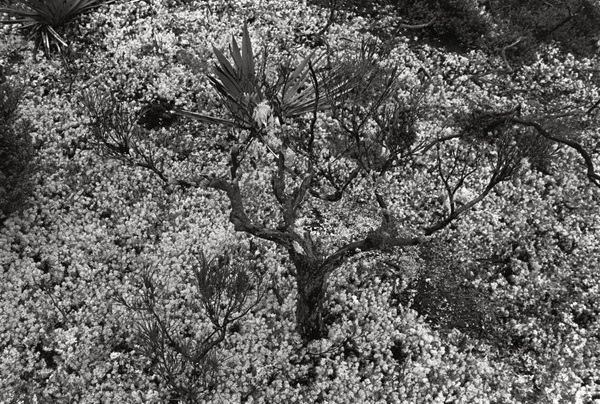

IT'S A BEAUTIFUL PLACE, Taukihepa, without all the politics, sitting down there at the bottom of New Zealand with its muttonbirds and early histories. I’ve been told the island used to be a happy place. Singing and laughing. Families would team up on Puketakohe, Heretatua, Timaru, Potted Head, and work the ground together. Seems a long time ago now. Back then, you caught only the birds you could work, and that means handwork, hand process. Preserve them in kelp bags. They didn’t have modernisation. Today, they have plucking machines! Money, money, money!

My family, Te Au, who are direct descendents of the original owners of Stewart Island, the ariki line of Kati Mamoe, got lost, pushed aside in the nineteenth century, and have struggled ever since. My dad paid the price with alcoholism, and his dad before him. There’ve been a lot of unpleasantries. You see, when the Maori wars went down, and Maori were decimated, it became difficult to work out who was who. Every man and his dog was jumping up, claiming this and that. Confused whakapapa. Only over the last few years have Maori worked on who really is who in Maoridom. The lineages are becoming clearer.

Taukihepa is one of the most unique, pristine places in the world—very few people get to enjoy such a place, so my five children are very privileged. And what I’m trying to do, in a Maori way, is to ensure that my kids don’t have the same problems my line have had. If it means I must die for these things, then that’s how it must be. I know no other way. I’ll fight to the end. You see, my generation, my brothers and sisters, we don’t really align much, but you’ll find my children’s generation and my sister’s kids, and all the others, they’re, like, tight, they get on better. They’re cousins, but they’re like true brothers. They love each other.

These past few years, I should not have had to fight others of my family and tribe for my rightful interests in the way that I have. Really, the onus should have been on others to sort out the difficulties. But they left it to me, put me in the hot seat, where the struggle has all but drained me emotionally, physically, spiritually. I’ve had to harden up. A war of attrition.

It hasn’t been easy piecing together my whakapapa. It’s been a real puzzle, like a jigsaw. I used to go from my mother’s line, because that’s all I ever knew. But, really, I’m a Te Au, and carry the Te Au name. When I was in Hastings once, where I was brought up, I said to my mum, “Why should I pursue the Russell line when I’m a Te Au? Don’t you think I should go back to the Te Au that’s stronger.” You see, my mum has Russell blood. On top of that, way back, Pene Te Au, my great-grandfather, married Emma Russell. So, my mum and dad both have Russell blood. My mum said, “You’re just as much Russell as Te Au.” But I figured, why should I go down the Russell line, when I’m a Te Au? I’m the Te Au line, yet, after succeeding to my father’s interests through the Maori Land Court, the lands they first tried to give me on Taukihepa were Russell, down the southern end. That was 2001, and now, 2004, the same battle grinds on, argument after argument, threat after threat. My marae is Murihiku, but we—my dad’s family—are more western. We have affiliations and ties with Murihiku but we’re more Fiordland. We didn’t have maraes, we had caves and grass huts. There wasn’t the marae you see there today in Invercargill. My tipuna were living in caves up to 1830, 1840. My turangawaewae is the Titi Islands and I’m very proud of that fact.

When you look at my mother’s side, my grandfather was a paramount chief. Tuwharetoa and Kahungunu. My grandmother’s side, Tainui and Te Arawa. They were the main lines. In Maoridom, an ariki married an ariki. They never really went down a class. That was something that put me on to my Te Au whakapapa. As well, Takitimu, which was the ariki waka and one of the original canoes to put ashore on this land, to end up where it did at the Waiau river mouth, and for the Te Au family there to be the kaitiaki, the guardians, that also told me. When I thought about these things, it would send shivers up my spine. Ever since I was a kid, I knew we were living like dogs, yet I felt we came from better. I don’t know. It was a gut feeling, just knowing. Maybe it was catching parts of conversations the way you do as a kid. You can’t quite work them out, but details stick, waiting to be resurrected.

When I was about six, I recall, it was all set that we, the whole family—mother, brothers, sisters—were going muttonbirding with my dad. Dad had sometimes talked about these mystery islands. Great excitement. But the night before, he went to the pub and the next day none of us were going. We had packed all our gear. It was a big adventure for us and it never eventuated. Maybe it was the difficulties down there, the pressures, because it’s been going on a long time. His dad had the same pressure. I honestly think a lot of the bad stuff at home was related to what was happening down there. He had his world stripped, my dad. It’s had a detrimental effect. His family before him were alienated and isolated. It’s been really frustrating. A hundred and fifty years, and it’s been imprinted on successive generations. Since then, it’s just been alcoholism.

Ruapuke, one of the muttonbird islands, was where the Treaty of Waitangi was signed for that area. What an occasion that must have been—colour and ceremony out there in the wild waters of Foveaux Strait. What I do know is that the ariki line, my ancestor Te Wae Wae, did not sign the Treaty, and who could blame him given what happened after. To commemorate the 150th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty in 1990, Ngai Tahu were inviting all the tribe’s families to Ruapuke while at the same time asking for signatures from those who were heads of the tribe to allow negotiations to begin for some sort of settlement with the Crown. Looking back now, you’d have to think that’s a cute twist. For a settlement, Ngai Tahu wanted to negotiate on behalf of Kati Mamoe who, back in the bad days, had married strategically with Ngai Tahu to save their bacon. I had got an invitation from Ngai Tahu to go down to Ruapuke. Well, invitations went to our whole family, and I thought, I’ll go and see my dad’s side. I was the only one from our family who took the opportunity to go down. My dad didn’t take it up, nor any of my brothers and sisters.

Now, it’s worth remembering that, at this stage, I’d pretty well given up on my Maori self, thoughts of whakapapa, even muttonbirds, and had been upto no good for some time. The invitation came as a bit of a surprise, and it made me trawl back over some of that Maori stuff I’d tucked away. I grabbed my partner and our three kids and off we went. I knew we had to arrive at Bluff Wharf on a certain day, and when we did we came across this Maori woman striding along the wharf.

“Excuse me, do you know where any of these Maoris are, going over to Ruapuke Island.”

“Who are you, boy.”

“I’m Dean Te Au.”

As soon as I said that, she said, “Hang on a minute, just wait here,” and went running, screaming to the rest of these Maoris. “Te Au on board.” They all came over—big hugs. The boat was full, but they just went, “You, you, you, off—you on.” From that point on I started to get this feeling these people are throwing the red carpet. What have I done to deserve this?

We got halfway to Ruapuke, and my partner said, “Your family must be something special down here. There must be something about your family.” Because it was just red carpet.

“Have you ever had oysters straight out of the sea.” someone asked me. The next thing I know, I’m sitting there and about eight women are surrounding me with knives, feeding me oysters one after the other. On the island it was the same. I don’t know, it was just never having known the people, never having been there before.

When I went, I felt like I was a nobody, but when I got there they didn’t treat me like a nobody, they treated me like a king. It was all new to me. Meeting the family, being on Ruapuke, was just awesome.

When I went, I felt like I was a nobody, but when I got there they didn’t treat me like a nobody, they treated me like a king. It was all new to me. Meeting the family, being on Ruapuke, was just awesome.

I talked to my uncle, George Te Au, about where my family lands were. I’d last met Uncle George ten years before in Invercargill while on a martial arts tour down south. My father and George were first cousins, their fathers were brothers. George was head of Kati Mamoe at that time. “It’s not Murihiku,” he said, “it’s the western side. You’re over there. Fiordland. You’ve got more lands over there.” I remember him pointing over to Fiordland. Yet, he’s a Te Au, so I said, “Why aren’t you over there.” It was kind of hard to work out. Ratimira, George’s grandfather, and Pene Te Au, my great-grandfather, were half-brothers. Ratimira is of Te Au’s second marriage, and Pene was of the first marriage. I think that’s where the problem for my family’s line has come from.

Oh, a lot of things happened on that island that time—the events, the aroha, certain little things. The old people, some who’ve died since, whispering to me, “These islands are your turangawaewae.” Don McKinnon, the government representative, and Tipene O’Regan, the Ngai Tahu representative, saying, “Boy, we want to negotiate with the Crown, we need your signature. The governor-general, Sir Paul Reeves, was there too. Tipene asked whether I had ever thought about wearing a Maori moko, “Because you look like our old chief, a reincarnation.” Tipene’s mother is a Te Au. When we used to see my dad and him together, you’d have thought they were half-brothers. There were these boulders on Ruapuke, and Tipene told me and my son to stand on them, and said that the highest-ranking chief stands on this rock. I was twenty-five. Who am I? crossed my mind.

I agreed to sign, to go into negotiations, but in the end, a few years later, I refused to sign the settlement. I remember when it came in the post. Even though I am Ngai Tahu, my position is strongly with Kati Mamoe. I saw that I’d be giving up articles one and two of the Treaty, and accepting article three. I’d give up rangatiratanga, my land and histories and resources. There were 500 of Ngai Tahu who refused to accept it, mostly Kati Mamoe and Waitaha because they knew they were separate identitities. As I said on television outside Parliament, how can you have one brother inside signing and another outside protesting and say that this settlement is for the whole tribe? It was a small but important protest of Waitaha and Kati Mamoe. They did a full-on haka on the steps of Parliament. I believed the Crown was paying up for old injustices but were creating new ones. Repeating history. As well, Ngai Tahu, I honestly believed, were going for a crumb and selling out future generations. But at that time, I couldn’t really speak because dad was still alive. My whakapapa was still his. It was up to him to speak up. But, in the end, he didn’t. It was too close. He didn’t have the fight left in him. Burnt out. We should have been involved more in the process. Kati Mamoe should have had an equal right to claim. Kati Mamoe were different, and the Waitaha people too. Hoodwinked. The wool pulled over our eyes.

Going to Ruapuke in 1990, wanting to find out more about who I was, kicked me out of crime, but it didn’t last long. No, I got back into it. The Notorious Mongrel Mob. You know, I was tattooed at ten years of age. Charlie Walford, the president of the Notorious Mongrel Mob, drew this design on my hand and asked if I wanted it tattooed. “It’s a Maori fishing net,” he said, “and if you put it on, whatever your hand touches, it’s yours.” I had a lot to do with the Notorious Mongrel Mob when I was younger, in Hastings and, later, nationwide. Oh yeah, I was a rebel with a cause, a little terror.

I was born 22 February 1965. From my birth certificate, my mother is Tanira Hemana Te Rohu Te Au, nee Kani, and my father, Kevin Jon James Te Au, from Invercargill, Colac Bay. My dad would shear every day, but drink at the end of every night. He was one of the best shearers of his time, but the majority of the money he made went on alcohol and party, party, party. That’s all I remember of my old man when I was younger: party, party, party. I remember the big parties all right. Five-day parties with a tent out the back of our house. We crammed into a double-storeyed State House unit in central Hastings. A lot of Once Were Warriors stuff going on. All his mates were Mongrel Mob. I can remember when I was little, armed cops kicking open the front door and fighting with my old man. They’d park outside for days on end waiting for him to sneak home. I had this heavy toy pistol at the time, and I can still see myself whacking one of the cops on the head, yelling at him to leave my dad alone. He was always in and out of jail. That’s why I never used to see him. I only saw him for two and a half years of my life. Alcohol, abuse, domestic violence was just about everywhere in Maori society around this time. Where there’s poverty there seems to be crime. Not that I understood these things when I was younger. You were just brought up in it. My old lady was trying to keep the family together. Eight kids. There was plenty of money on booze and cigarettes, and none on food. She was always out in the gardens, my mother, working in orchards, full-on seasonal, just earning money. Just to keep food on the table.

When I think of it now, I sort of had more freedom with my dad, and could do things with him my mother wouldn’t allow. He let me smoke cigarettes. He was anti-marijuana though. So I aligned myself with him. I could stay up at night on the weekends, serve beer for him and all his mates, run to the shop, get cigarettes and keep the change. I remember a lot of that. Yes, me and my older brother used to be the barmen. As we got older, a lot of that stuff took its toll, more on my brother than me. Fights and arguments. Every night it used to go on, and my brother was the one who had to try and stop it all, bear the brunt, become the father figure. He had to pool-cue my old man around the head, beat him, whack him with baseball bats, spades, flagons, you name it, to defend and protect my mother who used to cop it all the time, as well as the younger kids. It affected him. It affected the whole family. What happened in our younger lives, it’s not really something we can solve.

We left the ugliness of that State House unit when I was seven. My great-grandmother had died, and my mother was gifted her house and land in Pakipaki, about eight kilometres south of Hastings, where the lime works is. My mother still lives out there. We moved out to the country, to a big old house, a mansion almost, built in 1931 by my great-grandfather, Wi Te Kani, with acres of land. Sort of an estate. The last sheet of iron went on the roof as the great Napier earthquake struck, I’ve been told. All eight brothers and sisters—big grounds, plenty of room to play, run round in. A reprieve, even if my old man’s baggage did come with him when he sometimes turned up. Mostly he wasn’t allowed.

We went to the Pakipaki School there, a bilingual school. Years later, the school sang “Te Hokinga Mai’ on the return of the Te Maori exhibition from the United States. Even though we had lived in that lowest scene, there were a lot of times, out at Pakipaki especially, that are good memories, like going fishing, diving, getting our own food—those were the good things I remember. Most weekends, the whole family would be out on the coast or in the rivers collecting our own food: paua, crayfish, mussels, fish, pipi, watercress, puha, the lot. My brother and I nearly drowned once at the Haumoana river mouth. My dad had waded across the mouth at low tide to set a fishing net on the other side and given us strict instructions not to follow, just to wait. Of course, we didn’t completely listen. We waited fifteen minutes as the tide was coming in, and headed after him. A big wave came and under we went. My brother, who was older, managed to right himself but I stayed under. A mate of my dad’s, Ronny Wepa, reached in and saved me. I was drowning.

I was a little rebel at that time, seven going on eight, a little shitbag. Uncontrollable. I used to scoot up in the holidays to stay with my grandmother’s sister, Raukawa, in Matata, north of Whakatane. Her younger brother, Tini Fraser, would pick me up in his automatic Chrysler Valiant, a flash car then, and drive me to her place. We’d go different ways on different holidays: Waikaremoana, Taupo, Murupara to Reporoa, by-passing Taupo. I remember one time was when Mona Blades disappeared. It was the number one news. I’d live with Raukawa in the school holidays, Christmas, May, August. Somehow that’s where I always ended up. I’d go on my own, but there’d be some of my cousins there too. We were kids being kids — open playground everywhere. Damming up creeks, making our own pools, it was so hot up there in the summer. Into the bush, catching birds, shooting off the slug gun, even the shotgun. Play place!

Back in Hastings was play place too, but that’d end up in mischief and trouble. Boredom. We’d get together in a group and do the little rascal things. Pinching out of shops. I got caught first when I was four, my cousin and me. Finally, I ended up in the Youth Court. No surprise. Predictable. The court, very seriously, set me under the full-time care of Raukawa. I was eight, and I went to live with her for two years. It was strange at first, leaving family, but then like anything I just kind of flopped into it and realised that this lady was what I’d been looking for. She was old school. My cousin Clyde, who was at high school, and me, we didn’t have to do housework, dishes or cooking, weren’t even allowed to take a plate from the table to the bench. We were outside. Our job was to bring in food, chop wood, feed the pigs, mow the lawns and bring home food. We were told if we didn’t find a feed, not to bother coming home. So if the beach was foul, we’d head to the river or the bush and get what we could. We were our own supervisors. It was a freedom. Yeah, Raukawa, she was the star of my life. She had no husband and no men, but there were four teenage girls living in the house — her daughters, and two others she adopted, including the niece of her sister.

From the day I went to live with her, she taught me how to get my own food. About the only things we needed to buy were butter and sugar. She had all the knowledge of the old ways—catching and collecting her own food, surviving. Two years in a row with Raukawa, I grew big kumara patches. Her way was like this: whatever I grew or whatever I caught, I had to get it for the old people. Every day I had to knock on some old person’s door and gift them a fish, or an eel, or whitebait, or something. In return, they’d give me some Maori bread, apples, kumara plants for my garden—a barter system. It was my whole lifestyle for two years. One of the most enjoyable things.

When the dragline was cleaning out the creeks and drains around the Tawera river mouth and other places nearby, Raukawa would give me 100 sacks to collect eels in. The dragline would scoop out the drain to help it flow better and dump the debris up on the bank. I’d clamber over the piles in my shorts and gumboots, wet and dirty, collecting the big eels and throwing the little ones back. Days on end I’d do this. One sack a family. I remember Raukawa had an arrangement with the headmaster of Matata School. If the tide came in at, say, ten o’clock and it was whitebaiting season, she’d pull up outside and I was allowed to leave school and go fishing. I’d sit at my school desk watching the clock: one hour and I’m out of here. Perfect. She was seventy-seven when she died. Back when I lived with her she would have been about fifty. She died in 2002, while I was on the island. I didn’t know until I got off. No one told me. It upset me that I didn’t go to her funeral, that no one let me know. She was my mum. I used to call her my mum.

I do remember when I was younger, before going to school, we got taught a lot of Maori language, but at school we started losing it. I had a lot of Maori culture when I was younger. You’d be sitting around the house and all the old people would be talking in Maori. My grandfather, Te Rohu Te Heu Heu Te Kani, always spoke Maori. Very rarely would you hear him speaking English. He talked to me about whakapapa too because he could connect, he had the knowledge. Whakapapa started coming up when we were young, at home, on the marae, everywhere. We’d be hearing it all the time. Te Kani had been an instructor with the Maori Battalion. He used to parade and drill us in all the Maori war dances and stuff. I got a good martial arts training when I was younger too, starting with him on the marae. Kapa haka, taiaha, patu, poi, all the old arts. His sister, Bena Strongman, has taught a lot of people taiaha too. We’d go on Houngarea marae and have to practise and practise and practise All the young ones, boys and girls both. Over and over, until you got it right. Correct breathing too.

My grandfather taught me martial arts, Raukawa taught me how to survive and live off the land and the sea, and my father taught me to be a rebel.

Now that I see it, the old people would scan the ranks and they’d see certain things in individuals, quality traits. They cut a track for me, the old people, but I always went off it. Sometimes you’ve got to learn the hard way. What they taught me then, though, is a lifesaver for times like now. It’s come out a few times in my life. I’ve tried to get back on track, but I haven’t been strong enough to stay there. The old people wanted me alcohol free, drug free—you know, all things Maori. They maintain that it affects your whole well-being. A lot of them were steeped in the old ways and were bitterly disappointed with me. But at the same time, mine is a Maori way too. You won’t learn to swim sitting on the waka. You have to immerse yourself in the real world, take the hard knocks. I look at what they taught me and it was to survive. What I’m trying to say is, they gave me a bag of knowledge that I’ll carry around with me for the rest of my life. Knowledge that will ensure my survival, whatever I do, wherever I go. They were giving me the old gifts, mainly based around food and food-gathering, to ensure that I’d pass them on to my children.

I must have driven them crazy. I just did my own thing. I remember at ten years of age, I would jump on a bus in Hastings and come down to Wellington to live with the drag queens and tranvestites. I’d just turn up at their flats in Cuba Street. It was the Carmen days, and Chrissy Witoko. They looked after me. It used to be hard-case when Carmen was running for mayor—1977—walking down the street, a little twelve-year-old by that time and two six-foot drag queens. I was going round licking up posters and drinking in the nightclubs. I was my own boss. I would be there a couple of months, maybe three, and then back to Hastings for a week, and then on a bus and back to Wellington. You see, when I was ten most of my friends were thirty—they were adults.

Even when I went to secondary school my age was out of step. I’d been shifted up quickly through primary school, so I was only ten, just about to turn eleven, when I went to Hastings Boys High. I hadn’t even reached puberty. I was always picked on—I was the little fella at school. I couldn’t relate to my mother any more because of the way I had lived with Raukawa. I did my own thing. So, yeah, I just sort of wagged for a couple of years at high school. I remember my mum getting my fourth form report. I’d only been at school six days of the year but she didn’t know. They were all trying to get me back to school. My older brother used to drag me down to the bus stop, but the moment he took his eyes off me I was gone. We still get on, though, my older brother and me.

You know, I was only thirteen years and nine months the day I was to sit School Certificate, but I never sat it. Te Kani, my grandfather, turned up just before school and had a talk with me out on the grounds. He figured that everyone was doing School Certificate but no one was doing Maori training. He wanted me to leave and come back to Houngarea marae to live. That’s my home marae in Hastings, and the connection between Kahungunu, Tuwharetoa, and Te Arawa and Tainui. They’re all one big family. I didn’t need much arm-twisting. I was out of there right then. It was all part of finishing my moko Maori. I’d mow the marae lawns, do the cooking, set up for funerals and make sure the meetinghouse was prepared—that all the mattresses and blankets were out. Learning how to do the hangi. If there was a function, or anything happening, say a funeral, that was my job, to be down there in the morning.

I went to the marae for a year and a half, until I was fifteen. It was my home. My mates would come after school and we’d eat there. Sleep there too. Play bull rush, tag, running around at night with torches, shanghai fights, good mischief stuff. They’d get up and catch the bus to school from right outside. It was the centre of the community, the marae. They had a PEP scheme there at the same time. An uncle who had won a big sum in the Golden Kiwi, as it was then, donated a lump to the marae for building a combination tennis/basketball/netball court. The marae had fundraised through Housie, cards and hangi every weekend—everyone would be there—to build a new kitchen and dining hall, the wharekai, to plant trees and renovate the carvings on the meetinghouse. A full restoration programme. Whenever I go past now, I say to whoever I’m with that I helped plant those trees. The PEP workers—there were a good ten of them—would each give me ten bucks a week because I’d help them with their work, doing things like driving the tractor, making smoko, going down the shop, just helping with whatever.

The one steady thing in my early life, I suppose, was my martial arts training. It played a big part later. Without it, I reckon I’d be dead now. My mum ran a youth club she’d set up when I was at primary school, down on Houngarea marae, in the dining hall, although in summer we’d be outside, even down the beach doing martial arts training in the water. Every Tuesday. Then it changed to Monday and Wednesday, and then every day as we got older. It’s where I got back into the martial arts my grandfather had taught me and the others as little kids on the same marae. There were something like 200 of us at the beginning, but in the end, by the time I was fifteen, it was just me and my brother, Grant, at our instructor’s house, out in his garage. That was Charlie Walford, the president of the Notorious Mongrel Mob who I mentioned earlier. He’d been president of the Filthy Few. He died last year in a car accident. Charlie took us under his wing. He’d just got out of jail at the time my mother had started the youth club. She had helped him with his parole. He was a third dan black belt in martial arts, and started teaching us. To teach was part of getting him back into the community. He had been a New Zealand heavyweight and super-heavyweight champion — a big, strong man, tattooed everywhere, full-suited. Over six-foot, twenty-four stone. Not many people would want to get in his way. He taught us to take a hiding because, as he would say, if you know how to take a hiding, you’ll know how to give one. If I could take a hiding off him—and I did—I could take a hiding off anyone. When I was thirteen, I ended up moving in with Charlie on the weekends, staying with him. He was sort of like a father figure. We did Chinese martial arts for a year, but felt it was too soft for us, so changed to Japanese. Charlie brought in well-known instructors, such as Soli Percel, John Tahu from Wellington, Marty Stirling, John Marshall. Most of these guys were, or had been, New Zealand champs. We affiliated ourselves with Japanese Koku Shin Kai martial arts but later changed to Whanake Rangataua, Maori martial arts. I remember later touring all over the country.

It was professional martial arts that got me down south for the first time when I was fifteen. On tour. That’s when I first met Uncle George Te Au—he came to watch us fight in a pub in Invercargill. Took photos and gave us a feed at home, I remember. I had left Hastings and come down to Wellington, to Alicetown, to train at Marty Stirling’s gym for about six months. I had my blackbelt by that time. Charlie Walford was still in Hastings, but we’d hook up every now and then at tournaments. It was Marty who took us down south. He went to some sort of welfare organisation and got a grant—about $10,000—for pulling us off the streets. He bought a trailer with the money and we headed south with a portable gym and boxing ring. I was already Hawkes Bay and North Island champ for my division, and Marty put a challenge out to the whole of the South Island. There was only one taker, a Maori fella named Wiki who my brother, Grant, thrashed in Invercargill. We’d do demonstrations at tournaments most times and I can still hear the crowd wince as Marty—who was as big as Charlie—leapt up and came down full force on my midriff. I was much smaller than the eight-and-a-half stone I am nowdays, but I was like a rock. He round-house kicked me to the head at one venue and sent me over the top rope and out of the ring. We’d set up our boxing ring in pubs like the Waikiwi in Invercargill, and at the freezing works—we’d train running round the Riverton race course. We even fought in a jam-packed nightclub in Queenstown. Oh, the response that me and my brother got from Maori down there! We went to Southdown in Mataura and Ocean Beach freezing works at Bluff, and when I mentioned our name the Maori there were just, “Ooooooh’. Word would go all over: They’re Te Au, they’re Te Au, they’re Te Au. It was like it was later on Ruapuke. Me and my older brother were just treated like kings. There was something about it. Made me think.

My brother and I ended up in Wellington after the tour, in Brooklyn living with my sister and her partner. We all moved to Porirua after a while and out there shit hit the fan. Porirua was turned into a police state. I couldn’t walk up the street without being stopped four times and frisked. Riot squads, armed offenders, drug squads, smashed windows, kicked-in doors. I was already involved with the gangs. I had become a professional shoplifter. Running drugs from Auckland. Everything. I’ve seen things you would never believe, all marred by violence. Knives and guns. Yeah, seen it all. It’s interesting to me now how you can pull the wool over your own eyes. But that’s how it was for me then. If I hadn’t had my martial arts skills, I wouldn’t be here now. A lot of that training, when I was younger, was survival. It didn’t matter whether it was fishing or martial arts, it helped me through every stage. I figured it was my martial arts training, the discipline, that gave me a sixth sense — I could read the play long before it was happening, whether in a knife fight or something as simple as shoplifting.

I had a lot of guys looking after me, though. They were more or less like shields. Something about my background. They knew about my mother’s side and my father’s side, the whole lot. Even here everyone was older than me. I always seemed to have an escort wherever I went, all around the country to different chapters: King Country, Napier, Hastings, Auckland. They’d escort me in a convoy from Hastings and drop us off at King Country and they’d take us up to Auckland. It all related to my dad’s connections, I think, when he was younger, and mine too as they grew.

Setting out on my crime lifestyle I had wanted to get away from all my Maori stuff—the marae, funerals, any part of the culture. And, of course, that’s when I went right off the rails.

But I started falling out with some of the guys over the years—not the Mob, just some guys. Greed and drugs, serious drugs, going overboard, that sort of stuff. Needles. I never was a user myself. I hated the needles. I hooked up with some very heavy criminals through that time. Like an organised crime crew. There was a lot of it but it’s hard to sort of rewind the clock and focus on a particular moment. Maybe the shades are down.

Finally, I moved away from it all. It was going nowhere. It got to the point where I just wanted to opt out. After what I’d seen, enough was enough. But you don’t walk that easy. It’s a lifestyle, and changes take place over time. It’s not something that just switches on and switches off. To try to be hard on every decision. It takes a long time to reconstruct yourself.

Setting out on my crime lifestyle I had wanted to get away from all my Maori stuff—the marae, funerals, any part of the culture. And, of course, that’s when I went right off the rails. I didn’t start picking up the Maori stuff again until after my car accident in Wanganui—good following bad, although that was difficult to see at the time. I was well drunk and drove straight over a roundabout. Car turned on its side sliding towards a petrol station. When the car came to a stop I could have reached out and touched the pump. Too close. The accident landed me paralysed in bed for about six months. I had to be carried to the shower, the toilet, anywhere I wanted to go. I was with my partner in Titahi Bay, off and on, helping look after my eldest son while they all looked after me — my partner, her cousins, her brother, her mother and aunties. They were very good to me—tender, loving care. It took me years to actually walk by myself. Not so good, but being in bed gave me plenty of time to reflect on my life. A turning point.

It’s strange how things connect. When I got better, I ended up in a battle with ACC who’d tried to wipe my claim. They tried to say I never had a car accident, that I was making it up. I’d been going to specialists for three years! They’d wiped my claim off the computer. I had a five-year battle with them. Psychological warfare—seems to crop up a bit in my life. It’s too complicated here to explain the details of how they tried to hoodwink me, but eventually I was able to catch them out. The way I did that was through the police who’d arrested me after the accident and taken me first up to a doctor’s surgery. I tracked down the doctor who had a record of my visit that morning, as well as a record of the ACC payment for the visit. Bingo! I was paid out $27,000 for disability, pain and suffering. On top of that, the judge recommended an ex gratia payment as a matter of justice. But I’ve seen nothing of it. That’s coming up seven years now, and nothing.

As part of all this strife, I went to see John Miller, a law lecturer at Victoria University in Wellington, an expert in accident compensation. I’d wanted to talk to him about my ex gratia payment, some advice on an appropriate figure. When I showed him the case I’d got up against ACC and won, he wanted to use it as a precedent in a case he was presenting in the High Court the following week. He looked at what I had and said, “Dean, you don’t need a lawyer, you’re the guru,” and asked whether he could use my file—court decisions, correspondence, appeals, everything associated with my claim. He said, too, after looking at all my notes, “My fella, you see that door. Right now, walk straight in there and signup for university.” A week later, I was in lectures. I didn’t believe it. Incredible. I didn’t believe I could get in. That was 1996. I took up politics, history and sociology. He took his case to court and got a $263 million settlement for 500 ACC claimants. That’s more money than Ngai Tahu got!

For a Maori, then, going to university was like going to another planet and surfing with the aliens—jumping the fence, jumping the waka. I was buzzing that first day, a new world. You know, all my friends were just doing the same thing they’d been doing ten, twenty years before. This is what I’d been able to reflect on when I was laid up in bed. Coming to university changed all that for me. It was a vehicle to get me out. That’s why I came to education. It took me away from where I was. I had no support from anyone, not even my family. Yeah, even my family thought I was mad. There were a lot of things happening at that time—oh yeah, a lot of things. ACC, Ngai Tahu claim, family trouble, personal strife. So, I wanted to get an education, to learn how to deal with problems, to make sense of what I couldn’t understand, what I was going through.

It was a real culture shock. I didn’t know what a question was. Didn’t know what a full-stop was. Didn’t know what an essay was—didn’t know how to write an essay. Yet that first year I had to write forty-eight essays, all in long-hand. I was computer illiterate. I had been given a computer but no one showed me how to switch it on. I used it as a noticeboard, sticking stickies on it. I’d taken on three disciplines and it was sort of real stressful—most stressful time of my life actually, that first year. Having to turn up to class, to study and think, after where I’d been. In the end, I failed my history and sociology papers—but I did pass political science. I was rapt and decided to stay in. Getting through that first year in politics . . . I just continued. It took a lot, though, a lot of mistakes and start again, make mistakes, start again, but I got through it. Education was a way to move on. Without it, I’d probably be in jail or, as I’ve said before, dead.

From the beginning of 1996, the more I worked on my education, the clearer things became, particularly in my Maori world—getting back to my Maori stuff. With my dad, he’d lost his whakapapa, or rather it seemed others had lost it for him. Oh, he knew who he was, he knew what he had, but he went along with other people saying who was who in the Te Au line. He tried to tell us early on, but at that time we couldn’t believe my dad in anything because he was an alcoholic. He used to say, “I’ve got these islands down there.” He told us where they were, and what they were. But back then I’d just sit there going, “Bullshit, you old c. . t.” Tell him straight to his face: “The old man’s talking shit again.” He’d swear black and blue, but seeing is believing and we hadn’t seen so we never believed. Seeing the way he was living, his lifestyle, you’d never think someone like him had something like that. Yet he was right.

These issues wouldn’t go away, they just kept cropping up one way or another,causing fights and arguments in the family. Ngai Tahu had sent out a book around settlement time with a list of ancestors who were alive in 1848. If you could whakapapa back to one of these ancestors you could register as a member of the Ngai Tahu Trust Board. You needed to send your birth certificate and whakapapa. I knew of Te Wae Wae in my line, of course, and I could whakapapa back to him, but I wasn’t clear on the line before him. I wrote to the Maori Land Court asking for documentation relating to the whakapapa registered in 1848 by my great-great-great-grandfather, Te Wae Wae. And amazingly it arrived. They sent it. The ariki line. I grabbed it and gave it to my dad. “This is our lineage here, this is who’s who.” Yeah, it was exciting because that was the first time my dad had given me credit. I had pointed out something to him that he didn’t already know. I actually had to get my dad’s whakapapa for him. After that, he apologised to me, said that here was proof of what I’d been arguing and fighting about over the whakapapa. He realised I wasn’t loopy like everyone else was making out, that I wasn’t making these things up.

When I read it, I started thinking about it, and thought, Yeah, someone down there—down south—at some stage or other has fiddled with it to suit their own agenda. The whakapapa I’d been given down there, every time I looked at it, my gut feeling was, This isn’t right. When I got Te Wae Wae’s 1848 one from the Maori Land Court, the true one, it proved that it had been changed around, changed to suit others. And now I was angry. I felt we as a family had been shafted and no one was doing anything about it.

My last talk with my dad . . . I got sick of him not doing anything about his interests in the muttonbird islands. “Are you going to do it.” And he said, No. When I asked him why, he didn’t really have an answer. It was the last argument we had. We had a fight. I kicked him in the stomach over it. I felt he was useless. I told him to die, move out of the doorway—it’s a hard thing to say to your father—and let me carry on with the fight. He died two months later, but the week before he died he drove down to Wellington on his own, looking for me everywhere. I didn’t know that he was looking for me. I’d had no contact with the family because of all the trouble. My ex-partner searched round the pubs for me the night he’d gone into hospital back in Hastings. She found me in Bar Bodega at eleven that night. I spoke to her outside through the window of her car. She said he was in hospital and would update me in the morning. It was a still night, calm after a storm, but right at that moment a whirlwind spun around me, a sign, and I said, “Don’t bother, he’s dead.” And he was. So I never got to see him. I never got the chance to apologise. I feel bad about that.

My dad died 26 July 2000. The funeral was in Pakipaki at the marae, and in the bright winter sunshine of that late morning, a group of around fifty Mongrel Mob members, family too, friends and relatives, did two of the most fiercesome and awesome haka you could ever wish to see. To send him off. You could hear them for miles. You see, my dad had been clean for over seventeen years and had been running a Maori drug and alcohol rehabilitation service. He ran a halfway house for released prisoners too. He helped a lot of people clean up. He had gathered a lot of respect over his last years. Me? I didn’t shed any tears. I told my sisters when they crowded around the coffin inside the meetinghouse that he was just a shell in his coffin. At the cemetery up on the hill behind my mum’s house, the pall bearers—me, my brothers and some cousins—put the coffin alongside the grave, and as the priest started to pray, I said, “He’s dead, let’s get this over and done with, just put him in the hole’. Down he went. I began shovelling dirt on to him, and then jumped down to pat the earth firm with my feet. It wouldn’t be for another year, down on the island, that the tears would come for him. It was then that I gave my dad the respect he deserved.

A whole bunch of relatives had come up for the funeral from down south. At the end of it, as everyone was leaving, an uncle and aunt got my brothers and sisters and me together out the back of the marae, and invited us down to see the mysterious muttonbird islands and to stay with them on Taukihepa during the season the following year. The season runs from 1 April until the birds fly off heading north to the edges of the Arctic around the middle of May. I still hadn’t been there, so this was a big thing. Everyone seemed keen but in the end my sister’s boy and me were the only ones that went.

But there was still the matter of my father’s interests. To transfer Maori interests such as these from father to children, you must use your whakapapa at the Maori Land Court to prove succession through an ancestor who is an orginal Maori owner of Stewart Island. My mum—maybe she sensed trouble ahead—said, “Let’s get this in place,” and we applied to succeed. It took six months before the Court was ready for us. In the meantime, my seven brothers and sisters were putting together a whanau trust to group their interests and wanted me to be part of it. I got a phone call from my sister the day before we were due in court to get up to Hastings. They’d had a meeting and formed a whanau trust and wanted me to sign into it. Straight away on the phone I said no. I had a gut feeling. A whanau trust? If I signed my interest into that trust it would mean I’d be a spectator for the next three years. The trust would manage and control my interests. You see, my mission is my children’s interests, and right here already they needed protecting.

I was in Wellington and hitchhiked straight up to my mum’s in Pakipaki and we, my brothers and sisters there, argued and argued because I refused to sign. A whanau trust, no matter how many members, would only be allocated, one birding area. I figured they were limiting themselves before they’d even begun. The next day, while all the others went in cars to town, I hitchhiked in and an amazing thing happened. I was walking down the road leading to the main highway and bumped into two friends of my dad standing on the corner behind the marae, Mongrel Mob members. They said that they were aware of the problems I was having with the family and that my dad wanted me to stand up for my own rights. I felt as if these guys had talked with my dad before he died, as if they knew his wishes. We were speaking the same language. It was a weird fluke that meeting, but it gave me strength. In Court, I asked Judge Wainwright if I could take my own entitlement outright, to extract my rights, to have my succession separate from the whanau trust. And she agreed it wasn’t a problem. Today it’s clearly marked on the Court’s succession documents. But as soon as we walked out of the Court, a big family fight went down.

Before my dad died, the whole family had been accusing me of making up the whakapapa trouble, that I was imagining it. It was like psychological warfare. But my dad recognised I was on the right track when I came up with his Te Wae Wae’s whakapapa. They tried to put me in the psychiatric bin, tried to get me committed. Can you believe that? I had to go for a psychiatric assessment at Porirua Hospital. There was nothing wrong with me, as it turned out, and that gave me strength too. A lot of things were going down at that time. There was a lot of meanness about, bad spirits. Yet all I was doing was standing up for my rights and interests and those of my children. Every time, they became heated arguments, real heated. I didn’t like what they were doing, always trying to hoodwink me.

Otaki, my eldest, the youngest Tiemi, and the middle one Deanie boy, who went the following season, started to understand what was going on after they’d been to the island. They started seeing it first hand — the arguing and the fighting. They’ve started understanding what’s going on. They’ve given me a lot of respect since. Today, they know I’m fighting for them, to ensure that what I have been given will come to them, without being sidelined or taken away. I want to establish their rights. It was never about establishing mine. It’s about establishing my children’s rights. And now they can see it for themselves—the greed, the power and control.

When you succeed through the Maori Land Court, you succeed to the whole island and other islands and land holdings—all your father’s rights and interests. But it is the Titi Islands Committee representing the tribe who will determine your birding area, your manu, on the island. It’s through the tribe that you will receive a permit to build on a manu, thereby determining your right to that territory. My dad told me when I was younger that there were five islands, Rakiura, Taukihepa, Poutama, Mokonui and Mokoiti, and I can clearly remember him telling me the names of two manu: Heretatua and Puwai. I remembered that name, Heretatua, and knew that it was Te Au. But when I first went down to the island, after the invitation from my uncle and auntie at my father’s funeral, everyone wanted me at Puwai, the Russell end of the island. But I wanted to pursue my Te Au interests. My great-grandmother was a Russell, and my great-grandfather a Te Au. The Russells had Puwai at the southern end of Taukihepa, and my great-grandfather had Heretatua at the northern end. When they married, he went down to stay with her at Puwai—that’s where they lived. But I knew about Heretatua, and it is Te Au.

Around five months after dad’s funeral, late November—the muttonbirds had flown in from the northern hemisphere to breed by then—our family took his spirit, the kawe mate, back to his tribe, to Murihiku marae. About fifty of the family went down in a convoy of vans. A convoy of argument! When a Maori dies and he is from an area other than where he’s been living, it is correct to take the kawe mate back to his own tribe, to where he came from, his roots. On this occasion, I was the eldest male of my dad’s family on the marae, and my mum pushed me forward to be the speaker on behalf of the family. I knew all the old people on the marae this day because over the years I had taken up their various invitations. I’d met them. I’d participated. I stood up in the meetinghouse, acknowledged the reception we had received, and said that it was an honour to bring my father’s kawe mate home to his people.

The kaumatua in turn stood in their dark suits with carved toko toko in hand and pressed home in speech after speech that I was to be given the duty to reassert the Te Au rights and interests that had been downtrodden for many years. I was to be the kaitiaki, the guardian. Others had tried but failed. I was given this purpose. When I stood to accept this role, this honour, with humility, I made it clear, there and then, that this responsibility would be carried out on behalf of our Te Au children and future generations.

I walked out into the storm and threw my arms towards the sky and shouted, “Speak to me,” and at that very moment thunder and lightning let loose. A Maori sign. I looked back to Auntie Marge and she smiled.

But not even that settled the arguments. We were there for five days and I was set upon from all sides. And the old people could see it and shook their heads. They had seen it all before. On the day we were leaving, sitting round a table in the dining room, I asked my Auntie Marge, George Te Au’s sister (she was the oldest living Te Au at the time), “How do I get to go muttonbirding? I want to go.” I was going for sure, but it was all new to me and I wanted details. I had in mind a lasting Te Au right to be there. This is only a couple of weeks or so before we went to the Maori Land Court. My dad’s sister was sitting right opposite me.

“Excuse me, Dean, you want to go muttonbirding.” There’s an edge to her voice. “Well, if you want to go muttonbirding, your dad got it from my dad, so you have to go through me.”

Everyone had their agendas. Normal, I suppose.

Auntie Marge, her fist went straight down on the table. “Boy, you don’t listen to her.”

She walked away, came back and gave me all this documentation, some of it about past injustices on the muttonbird islands, one of them back in 1917. “Look at this, boy. You don’t need to go to her, you have your own rights.”

And my aunties and my older sisters started arguing. It had been like this all the way down from up north. Here too on the marae all week. It just wouldn’t stop. I was sick of it and sick of them, always at me.

On the last day, I was pretty down and wondering whether I really wanted to be kaitiaki, whether I wanted this responsibility with all the strife. I told my Auntie Marge that I wanted to give it back, give back this job the old people had given me. I even asked how come they’d given me my dad’s mana in the first place when I’ve got older brothers and sisters? Shouldn’t it go to one of them? You see, as one leader dies, his mantle is passed to one of his descendants, one chosen by the extended family. The old people scan the ranks. They had wanted me to carry the burden. But with all this bad karma from my own kin, I’d had enough. As far as I was concerned, I told Auntie Marge, it could go to my other brothers and sisters.

Auntie Marge called everyone back into the meetinghouse. “We’re going to sort this out.” She was a slight, elderly lady, Auntie Marge, small but with a big heart and a heavy-duty will. She had a deep sense of correctness. She was a light in amongst all this madness. The old people said, “No, we’ve given the responsibility to Dean and as far as we’re concerned it’s to stay there now. All the problems you’ve had you’re not to take them out of this meetinghouse.” They said it’s full and final, that’s it, under Maori law.

We came out of that meetinghouse to head for the vans. We’d said our goodbyes to the tribe. As our group congregated on the verandah, rain and hail came down. Everyone sprinted for the vans. I stood there for a moment and thought, Yeah, bring it on. I walked out into the storm and threw my arms towards the sky and shouted, “Speak to me,” and at that very moment thunder and lightning let loose. A Maori sign. I looked back to Auntie Marge and she smiled.

My first encounter down south with muttonbirds was with my nephew, Cedric, who was about to turn sixteen. For the two weeks before heading to the island for the first time, we camped on the beaches around the southern coast never too far from Bluff. One late afternoon, after a day’s fishing off Bluff wharf, we bought some fish and chips and wandered across to the beach behind the Ocean Beach freezing works, as they were then. We lit a fire and while the two small cod we’d caught earlier cooked along with some paua, we were presented with a stunning two-hour extravaganza of muttonbird frenzy feeding less than 200 metres offshore—tens of thousands of birds. It was magic.

We’d provisioned up in Invercargill the day before we left out of Bluff on the catamaran. When we hit Stewart Island the birds were everywhere, all the way down to Taukihepa, sometimes in huge flocks skimming the water, rising with ease, then sweeping down in a constant rotation. You’d see birds flying on their own scouting for schooling fish. Somehow, they let others know and tens of thousands would arrive for the same sort of frenzy feeding we’d seen off the beach. From the moment the cat left the wharf, Cedric stood with the captain, holding on with both hands, while we were drinking down the back, and didn’t move from his spot. We took the east coast route in four-metre swells. As the cat rose and then slammed down, over and over again, Cedric would end in a squat, pull himself up and yell, “Awww, Uncle Dean, awesome.”

Rounding the south cape of Stewart, my first site of Taukihepa made my heart race. It was like a powerful magnet pulling me into its spirit. Overwhelming. I took on Cedric’s excitement. But it was more. I was moved beyond words. Tears came to my eyes. My dad’s korero, what he’d tried to tell us. I was coming home.

That first season down on the island, my Uncle Norman, the grand master of muttonbirding, taught me the whole process. Wax on, wax off, wax on, wax off. I can still hear him saying it. It got to the point where I called him Mr Miyagi out of The Karate Kid. He had that look. He taught me how to extract the young birds from their burrows, to catch them at night later in the season when they came out in the wind and rain to shed their down. I would bite their heads in the old way—an instant death. Hand-plucking, gutting, waxing, salting. I was taught by the best. I wasn’t an expert by the end of the season but I had the basics. And I wanted to come back next year. The way it works, you have to be there for the first year, find a site, then the next year you get a permit from the Titi Islands Committee to build, and then that’s your birding area, your manu. There are twenty-two birding sites on the Taukihepa.

Uncle Norman and Auntie Carol walked me over to the committee chairman at Murderers Cove. I asked him whether I had a right to build, and then asked whether I could on Heretatua. He said, “Go for it.” It was getting late in the season and I still hadn’t been to Heretatua. Some birders were wanting me to build down the southern end where I’d been staying, the Russell manu, but that’s not what seemed right to me. In our first days down there, Cedric and I had wandered around the island getting lost and finding our way again—my way of getting to know the island. We did the mileage, although we hadn’t reached Heretatua. On one of these meanderings, I was challenged by some young birders. “Who do you think you are coming down here? Don’t think you’re going to build. We’ll burn your buildings.” These people weren’t beneficial owners, they didn’t have the right to challenge me. I had succeeded through the Maori Land Court by this stage. I was a beneficial owner.

Near the end of the season one of my aunties says, “Why don’t you go and find your section.” Some cousins heard on the radio that I was wanting to find Heretatua but didn’t know how to get there. So they came on the VHF and offered to come down and pick me up. They had to walk three hours, right down to Puwai, and then escorted me up to the ridge to Heretatua. The old people had said to me, “You’ll know, you’ll feel it.” When I arrived, I just felt it. This was the place. Heretatua. I knew. Home.

I went back to my auntie and said I’d found my manu, Heretatua. Things got a little crazy after this. It turns out others were wanting Heretatua. As well, I’d had an argument with another birder who threatened me over a birding track I’d cut. He wasn’t a beneficial owner. Everyone went crazy. Yelling and screaming. Threatening. “No, no, no, you can’t have Heretatua. You’ve got to go down over there, over there, that’s where you belong, the Russell manu.” They were meaning the southern end of the island. “No, I’m a Te Au,” I said, “I’ll go back to where the Te Aus originally were, Heretatua.” A big family fight, and it turned into one big hell of a mess. It just went mad. I was ordered off the island. They had ordered off a beneficial owner! I was given an hour to get off. I don’t think they realised I had succeeded through the Court. I was ropeable. As I left on the boat, I thought, I’ll take the hiding now but I’ll be back.

I found my way to my sister-in-law’s in Invercargill after the boat dropped me at Riverton wharf. She and I talked about what had happened, and from her house I wrote a letter to the Titi Islands Committee applying for a permit to build next year. I lodged it with the Department of Conservation in town, then flew back to Wellington to wait.

The next Titi Islands Committee meeting was a little under a year away. A long time to wait, a long time to stew—a long time for everyone to stew. I flew down from Wellington in February the following year for the permit day meeting at Murihiku marae. One of my aunties picked me up the next morning. I had only just walked into the meeting in the dining hall when I heard my name: “Is Dean Te Au here.” I was asked to come up and explain who I was and what I wanted. I told everyone that I was a direct descendant of the original owner of Rakiura, Stewart Island. I explained my whakapapa, that I had a succession order from the Maori Land Court, and I was on Taukihepa in 2001, had found a site, Heretatua, and wanted a permit to build.

I can still see the faces of the tribe, the muttonbird whanau, as I walked from the front of the hall that morning. There had been a prophecy in the tribe that the true owners would come back one day and eventually others would have to move over. Don’t get me wrong. I didn’t think for a moment that that related to me, but it was well-known throughout the tribe. Each row I walked past I could hear comments: “Don’t touch him, he’s head of the Mongrel Mob,” which I wasn’t; “He’s the owner, give it to him, he’s the ariki.” I’m not the ariki. That passed to my eldest brother when my dad died. But I’m of the ariki line and I’d been given a responsibity. I was nervous, you know, but I felt strong, correct. My family had been fighting this for years. I stood at the back of the hall for the debate, thinking, This is for my children. People stood up all over the hall saying that it belonged to them, or to give it to me, everything. It went on for an hour and a half. Some tried to put in the too-hard-basket, put it aside. But then, some of the aunties stood up and said, “We want to deal with it now, it’s been going on too long.” So they put it to a vote and Heretatua was given to me. The people gave it to me. I felt humble, but I also felt vindicated. I was made a supervisor too. You know, here I am, only just out of muttonbirding kindergarten, and they make me a supervisor. I got thrown in the deep end.

The thing about Heretatua is it’s exclusive, a palace. Everyone knows the best birds are there. But that’s not it, that’s not what it’s about for me—best birds, best money. Heretatua has got some sort of spiritual connection. In the old days, they’d say that the ariki lines could communicate with the ancestors, the gods, and this place has that feel. It’s powerful. It stirs emotions, and not always good emotions. But it’s a true treasure.

I took two boats down for the 2002 season, one for my six builders, and the other for my kitset sheds, including my sister’s, that were to be helicoptered off once we reached Taukihepa. It’s a rocky sea landing at Heretatua, and in the wrong wind it can be pretty wild. My partner, Debbie Ward, had poured a lot of money into helping me establish myself on Heretatua, and the tribe had put their faith in me. I wanted it to go well. Otaki and Tiemi were with me, which made me feel good, and my elder sister and her husband came too. We didn’t get on too well, my sister and me, over all the family issues, and on the island it didn’t improve between us, not from the moment we arrived. People thought they could push me around, treat me like a slave. On my own manu! A beneficial owner! You know, the best time down there was at the end of that season. Everyone had gone—that’s the rule—leaving only seven of us on: supervisors, committee. Me and Tiemi stayed and had the whole northern cape from Murderers Cove all the way round to Potted Head to ourselves for a whole week and a half. It was the best time, just me and Tiemi, my youngest. We were the last ones off the island that year.

2003, same story—others trying to gain control of Heretatua over my rights and interests. And now, as the next season approaches, they’re still trying. Even those who don’t have the right to succeed to Taukihepa. I may not have done a lot right in my life, I may not have been as humble as I should have been at times, and I may have made mistakes on the muttonbird islands, but I’ve succeeded to my father’s interests in the correct way and I’ve stood in front of the tribe in the correct way. I have my rightful interests and I will stand up for them. I want my children to get on with what it’s really about: muttonbirding, enjoying the world of their ancestors and the treasures they left.

DEAN TIEMI TE AU © 2004