texts

2014-08-28

‘Muttonbirds—part of a story’, Greg O’Brien, November 2005

“A vast underground rumbles beneath Bruce Connew’s photography. Over the past three decades, his images have often depicted acts of digging down into the earth.”

DUG IN, DUG OUT

‘Muttonbirds—part of a story’ by Bruce Connew with Dean Tiemi Te Au

A vast underground rumbles beneath Bruce Connew’s photography. Over the past three decades, his images have often depicted acts of digging down into the earth. Trenches and dug-outs run through his photo-essay about a Burmese ‘secret war’ which was published as On the way to an ambush (Victoria University Press: 1999); elsewhere he has photographed the turned and planted fields of Fiji; and the 1981 series ‘Beyond the Pale’ documented that archetypal underground figure, the West Coast coal miner.

Not only is Connew fascinated by processes of working the land—taking Jean Mohr rather than Sebastião Salgado as the model—he is a particularly astute observer of the act of breaking open the surface of the earth.

In Connew’s ‘Muttonbirds’ we find ourselves staring into a plot of land that has been broken open by birds. The site at the centre of the series—the island of Taukihepa, off the south-west coast of Stewart Island—is pock-marked with the entrances to underground nests. Even before the arrival of the shovel and wire wielding muttonbirders, it is a porous landscape.

And, like the surface of the island, the surrounding sky and sea are also pitted with flecks of blackness: the shapes of birds flying. While muttonbirds are known for their shambolic crash-landings around nesting sites, in flight they are supremely organized and graceful—a fact dwelt upon by Connew’s camera. ‘There is an elegance about them’, he observes. ‘Like Indians in a street in Delhi, they don’t bump into each other.’

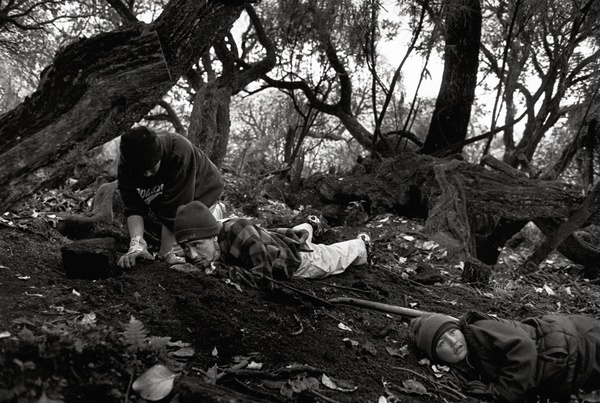

A sequence of thirty photographs, the photo-essay follows these migratory birds to their nesting grounds. It also follows the seasonal migration of the muttonbirders who ‘harvest’ them. Taukihepa is an unfamiliar and disconcerting environment. Muttonbirding, as presented here, is Māori customary practice with Swandris, tee shirts, cross-trainers and ski-gloves on. In the shadowy gloom of a coastal area, we witness a strangely inverted process where, rather than looking skywards, hunters reach down into the earth to extract the birds from their nests.

Like infantrymen, the muttonbirders hug the ground.

Muttonbirding is an uncompromising and unglamorous business. In one photograph, a boy kills a bird in the traditional manner, using his teeth; later in the sequence a muttonbird chick, dead and already plucked, is shelved in the branches of a nearby tree. Like infantrymen, the muttonbirders hug the ground. Whereas ‘On the way to an ambush’ was characterised by images of the isolated limbs of sleeping or crouching soldiers, their bodies concealed in trenches or just beyond the camera frame, ‘Muttonbirds’ reverses that equation and has the arms of the muttonbirders vanish inside the earth, leaving their heads and bodies visible.

‘Muttonbirds—part of a story’ is co-authored by Dean Tiemi Te Au, who invited Connew down to the island. In their book, Te Au tells his life story—an absorbing but distressing tale which can be thought of as one panel of a diptych; Connew’s photo-essay being the other. Both ‘stories’ lead us inexorably towards the island and the issues that lie at the heart of it. Taukihepa remains a site of struggle—not only between the elements, birds and humans, but also between different hapu. Land claims on the island are currently being contested and, in the course of producing these images, Connew was evicted from the island—Te Au and his two sons left with him in protest.

“When a sequence starts, the images are ahead of my understanding. To complete a sequence I must use images which are behind me… Camera and Eye are together a time machine with which the mind and human being can do the same kind of violence to Time and Space as dreams.”[1]

While the sequence of images on the Gallery wall is the same as in the book, the Gallery environment provides the more immediate account of the argument of the ‘essay’; with its juxtapositions of earth and sea, darkness and light, and the shift between the adult birds wheeling above the ocean and the chicks awaiting their fate back on the muddy slopes. The photographic narrative moves eloquently between images of entrapment and freedom.

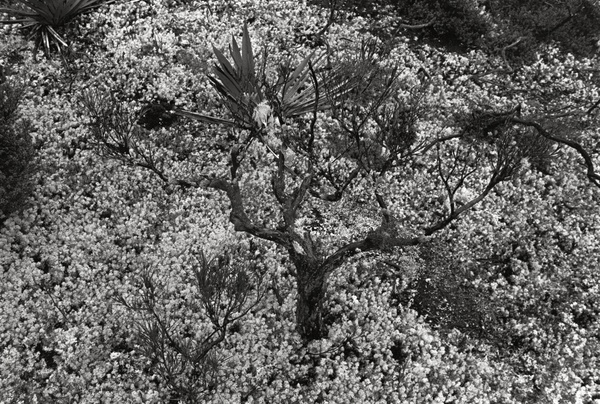

Aware of the loudly-ringing symbolism of boats, voyages, islands, birds and the hunting of birds—as in Coleridge’s ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’(1797-98)—Connew adopts a manner which is pointedly undemonstrative and plain. In the final three images, the birds recede into the distance—they are departing or else the photographer is traveling away from them. As a fade-out, it is almost cinematic. But Connew would never allow the closure you would expect of a ‘good movie’. He is a teller of unfinished stories, of unresolved plots. We are offered only segments: an approach from the sea, a stand of trees, a rectangle of soil. These fragments make up the parts, and the ‘part of a story’, denoted in the exhibition’s subtitle. The whole story remains inscrutable and inconclusive.

The half-darkness which dominates the land-based images in the photo-essay mirrors the complex and oblique issues of entitlement, acknowledgement and ownership that smolder in the depths of these photographs. If Connew admires the labour and commitment of the muttonbirders, his images could never be described as celebratory. This is a subantarctic narrative rather than a subtropical one. And the matter-of-factness of these photographs is itself a part of a strategy to disrupt a number of photographic conventions. As pieces of bird photography they are evasive and ungainly. As far as landscapes go, they are anti-scenic, with Connew appearing content to line up a few horizons seen through a fuzz of bird-activity, some trees and not much else. If, in one image, we see tiny flowers like constellations on the black soil, Connew’s exposures generally seem to encourage the encroaching blackness—a darkness which cauterizes alluring texture or detail. This is a low rather than a high adventure.

“When a sequence starts, the images are ahead of my understanding. To complete a sequence I must use images which are behind me… Camera and Eye are together a time machine with which the mind and human being can do the same kind of violence to Time and Space as dreams.”[1]

While the sequence of images on the Gallery wall is the same as in the book, the Gallery environment provides the more immediate account of the argument of the ‘essay’; with its juxtapositions of earth and sea, darkness and light, and the shift between the adult birds wheeling above the ocean and the chicks awaiting their fate back on the muddy slopes. The photographic narrative moves eloquently between images of entrapment and freedom.

Aware of the loudly-ringing symbolism of boats, voyages, islands, birds and the hunting of birds—as in Coleridge’s ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’(1797-98)—Connew adopts a manner which is pointedly undemonstrative and plain. In the final three images, the birds recede into the distance—they are departing or else the photographer is traveling away from them. As a fade-out, it is almost cinematic. But Connew would never allow the closure you would expect of a ‘good movie’. He is a teller of unfinished stories, of unresolved plots. We are offered only segments: an approach from the sea, a stand of trees, a rectangle of soil. These fragments make up the parts, and the ‘part of a story’, denoted in the exhibition’s subtitle. The whole story remains inscrutable and inconclusive.

The half-darkness which dominates the land-based images in the photo-essay mirrors the complex and oblique issues of entitlement, acknowledgement and ownership that smolder in the depths of these photographs. If Connew admires the labour and commitment of the muttonbirders, his images could never be described as celebratory. This is a subantarctic narrative rather than a subtropical one. And the matter-of-factness of these photographs is itself a part of a strategy to disrupt a number of photographic conventions. As pieces of bird photography they are evasive and ungainly. As far as landscapes go, they are anti-scenic, with Connew appearing content to line up a few horizons seen through a fuzz of bird-activity, some trees and not much else. If, in one image, we see tiny flowers like constellations on the black soil, Connew’s exposures generally seem to encourage the encroaching blackness—a darkness which cauterizes alluring texture or detail. This is a low rather than a high adventure.

Finally, we are left somewhere between the static electricity of the birds wheeling above the frayed ocean-surface— these flying ticks and crosses—and the slow, damp labour of history and culture. ‘Muttonbirds’ has now also become a part of the photographer’s story—a new chapter, shot surprisingly close to home, but which revisits many of the themes Connew has explored elsewhere in the world: the relationship of humanity to nature, the ways in which territories are contested, and the complexities of life both within and between cultures.

[1] Minor White, ‘mirrors, messages, manifestations’, New York: Aperture, 1969, p. 67.

GREGORY O’BRIEN / 11.2005