texts

2014-08-21

‘Press Escape to Cancel’, SPORT 24, Summer 2000

“Three towels hung from a line that stretched the length of the bathroom. As I looked up from their bath, it crossed my mind that they may never see these towels again.”

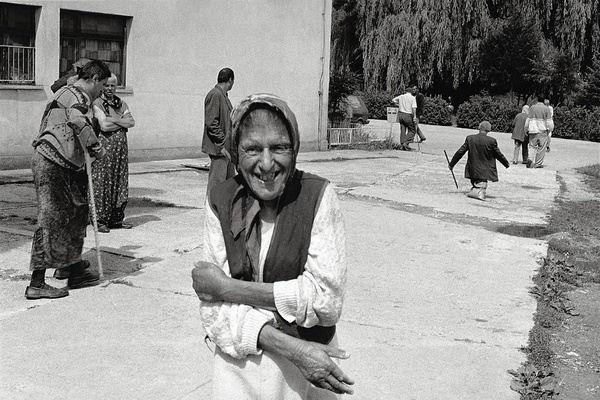

A MAN AND A WOMAN in a small red car reversed along the dirt berm towards me. I had been hitchhiking less than ten minutes. The previous evening, in Lazio’s bar, I had celebrated the Albanian Kosovars’ return with twelve men, including the man driving the small red car. He reminded me of this, because I didn’t recognise him. We established, in and out of gesticulations, and some English words, that his wife worked in a laboratory, or that’s what I thought we had established. When we reached their destination, I looked out the car window while gathering my overnight bag and camera, and observed, through a high wire fence, two men in pyjamas lying in long grass under a warming sun. In the way that photographers do, I took two quick photographs. On seeing me do this, the man from the small red car waved me towards the guarded entrance while his wife turned and grinned embracingly. I pointed to my camera, and then towards the entrance, and he laughed loudly, shouting, “Free Kosova!” She laughed heartily too. We were at Enti Special Hospital for the Mentally Ill. The wife was the doctor, and her husband was delivering her to her first day back since the bombing began.

Ismete Pajaziti, a teacher in Ferizaj, held up her wedding photograph from thirty years ago. Her eldest son sat alongside her. She said the Serbs had come, on April 11, to Radivozc village, where she and her family had sought safety. The Serbs demanded her husband cross himself, in a Christian way, and he couldn’t.

“Are you an Albanian?” “Yes.”

“Are you an Albanian?” “Yes.”

“Are you an Albanian?” “Yes.”

They shot him there and then.

A professor from Skopje’s university impatiently pulled a square of card from his wallet. We were enjoying Turkish coffee after lunch. The card listed the birth rates of Macedonia’s various ethnic groups. It was clear that the Albanian ethnic group was the most reproductive. He presented this evidence as plain proof of Macedonia’s Albanian “problem”.

Press Escape to Cancel, the title of this essay, is a repeating line from one of Jabir Derala’s love poems. Jabir is a Macedonian poet, writer and journalist. The other day, I asked him, amongst other things, to describe his ethnicity: “My father is mixed Albanian and Turkish. My mother is mixed Turkish, Croat (Dalmatian) and (a bit) Iraqi. My blood is probably even more mixed, but I don’t have time to explore it . . . it’s not a jarring question. I find it very exciting. But, not extraordinary, because we on the Balkans, as the rest of the world, have mixed blood more than we are ready to admit. Somewhere it’s a starting point for beautiful achievements, and somewhere it’s a reason for bloodshed . . . I was raised as a cosmopolitan, a citizen of the world, with love for people, regardless of their backgrounds. I am proud to be different. I am completely aware that it brings trouble very often. Almost always, when we mention Balkans (and, not only) . . . being different brought my father a bullet in the head in 1992 in Stolac. Killed by a Croat. Should I hate Croats, then?! I am a bit of a Croat (25%), too. So, I have to hate a part of myself.”

These photographs, quickly developing in the hands of the refugees, would be proof, in the absence of other identification that they were who they were.

The empty picture frame, hanging from the wall at the end of the bed, had contained a Kosova landscape, hand-stitched by Musa Kameri’s mother. Serbs had looted the picture. As well as the empty frame, Musa had found, beneath the shambles of his ransacked home, a packet of passport photographs of a Serb father and son, or whom we all took to be a father and son—the faces of the looters.

I spotted a UN worker with a Polaroid camera, darting in and out of the ranks of returning refugees at Macedonia’s Blace border crossing. He even climbed aboard buses waiting in the long queue, urging people off, so he could photograph them. These photographs, quickly developing in the hands of the refugees, would be proof, in the absence of other identification that they were who they were.

I stayed two nights in separate and abandoned Serb apartments. In the second, I had a bath, a splendid hot bath, and shaved in the same mirror last used by the absent owners. They had been gone several weeks, but had left everything, even curdled milk on the bench, as if they had expected to be back in the afternoon. Three towels hung from a line that stretched the length of the bathroom. As I looked up from their bath, it crossed my mind that they may never see these towels again.

BRUCE CONNEW /01.2000