texts

2014-08-19

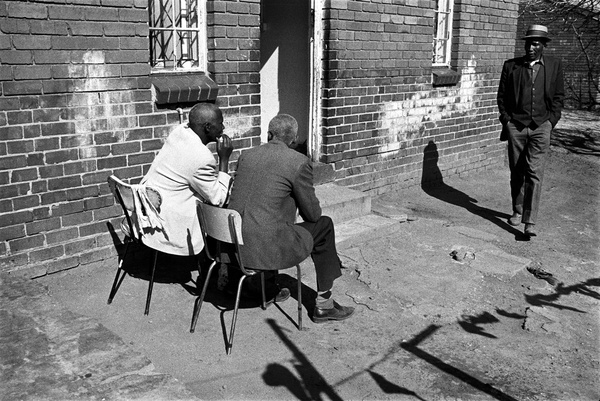

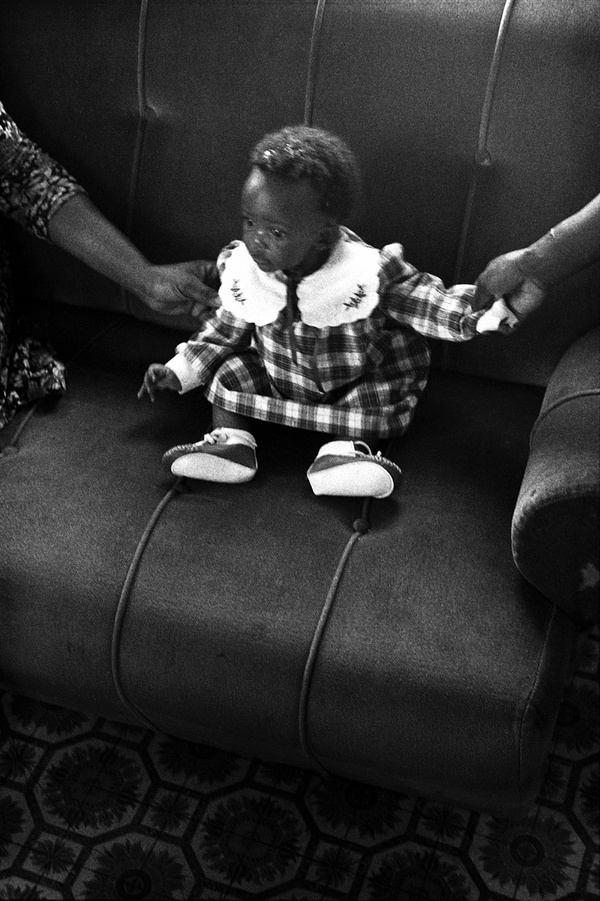

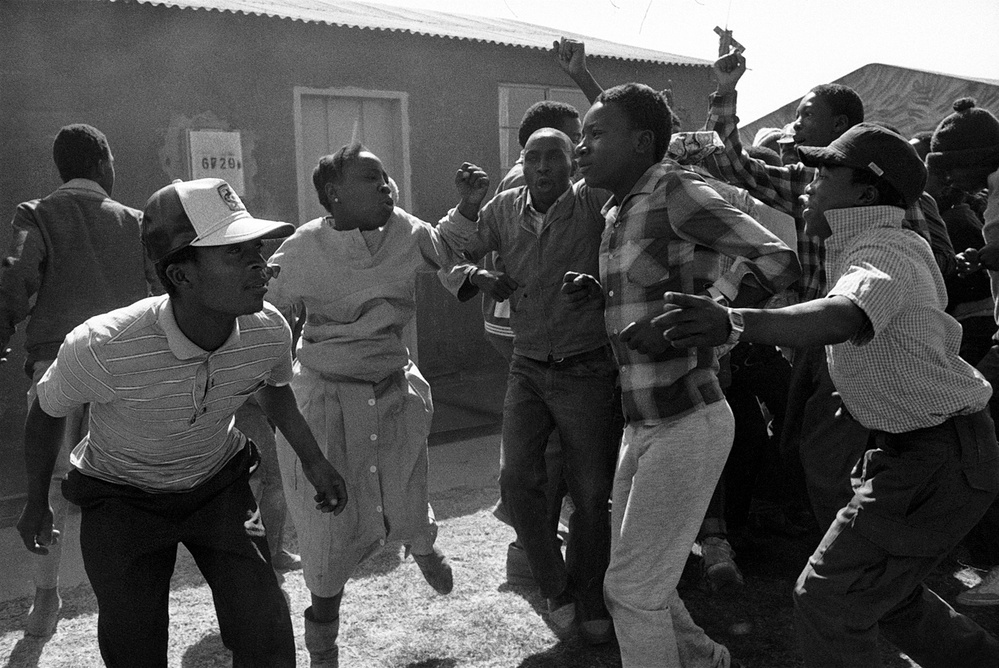

‘South Africa’, Vernon Wright, 1987

“A few yards away from the man at the organ, on the same verandah, a tall white man is being stabbed.”

ON A WIDE HOTEL verandah in Durban a man sits at an electronic organ and plays a tune from the 1940s. It is sundowner time, that hiatus between afternoon and evening during which settlers—in the colonial tradition—sit with their drinks and watch the sun flare across the navy blue sky before disappearing. Before Africa returns to blackness. The devices to keep the night at bay are fragile: electric lights disappear into the blackness after a few steps away from them. The interior of cars offer a sort of security. It is illusory, but it is better than nothing. I know a man who has been fighting the African sundown every night for twenty-five years, resisting his daily death with the ritual of the sundowner.

A few yards away from the man at the organ, on the same verandah, a tall white man is being stabbed. The coloured lights along the Durban waterfront have been switched on and across the wide street the seaside mardi gras is closing down for the night. There is a steady stream of traffic finding its way along the Marine Parade to the northern beach suburbs. Two black youths in brightly coloured shirts stand behind the stricken white man. One of them has a short-bladed knife which he plunges in and out of the man’s back. Then they both turn and flee down a side street and into the night.

By the time I draw abreast of the scene the wounded man is being held upright by other patrons. A black waiter in a red jacket and fez with a black tassle has appeared with a mop and is already cleaning up the spilled blood. In the distance comes the wail of an ambulance siren. Action and reaction occur with remarkable speed. The stabbed man doesn’t know whether to allow himself to be carried or whether to walk unaided to the ambulance. He walks, staggering slightly, an ambulance man on each side of him, his arms pulled tightly in against his sides, forcing his shoulder-blades back to help staunch the flow of blood.

Did he live or die? I search the papers the following day but there is no mention of the incident.

Did he live or die? I search the papers the following day but there is no mention of the incident. After the ambulance leaves, a small knot of white people gathers on the pavement to discuss the incident. One of the men approaches me and says it is just as well for the two kaffirs that he hadn’t been there when they were doing their stabbing. Another remarks that it is time we stop treating them with kid gloves. The group vow that they can put an end to all this, given guns and permission. I don’t reckon they can, but I don’t say so.

The stabbing we have just seen on the verandah was probably just plain criminal rather than political—a minor statistic in this normally placid, hedonistic city where some seventy people have died violently during the past couple of weeks.

That night, a few blocks away in the town hall, the State President, P.W. Botha, was to make a major speech to the National Party Congress. The speech has been previewed like perhaps no other in modern South African history. The President was expected to announce major structural changes to the system of apartheid, and perhaps even to pave the way for its eventual abolition. In a series of confidential briefings, Foreign Minister Pik Botha has told foreign journalists and government representatives during a visit to Europe that the segregated homelands would be dismantled if their inhabitants wished them to be and reintegrated into the South African state. There would be common and equal citizenship for all blacks in the central political process.

The prospect of such change had electrified the English-language press, and throughout the world, it seemed, a complete turnabout in South African Government policy was expected. ‘Newsweek’ magazine, for example, based a cover story on the expected reforms. And when he got up to speak that night President Botha was heard live on television not only in South Africa but around the world.

We watch the broadcast in the television lounge of the Empress Hotel. Downstairs the main bar is filling up with young white revelers more interested in a visiting rock group than in Botha, and soon the hotel vibrates to the thud of an electric band.

The President hints that influx control, one of the most hated of the apartheid laws, could be on the way out. He is ready to negotiate a new constitutional dispensation to include blacks, but he rules out universal franchise and he vetoes suggestions of a fourth chamber in the tri-cameral Parliament. He dismisses completely the possibility of an unconditional release from prison of Nelson Mandela. And he warns, “Our readiness to negotiate should not be mistaken for weakness. Don’t push us too far, for your own sakes.”

In the doorway of the lounge a black waiter watches Mr Botha intently, his shoulders hunched and jutting forward. An out-of-town white couple discuss their journey home, pausing occasionally to glance at the screen. Downstairs in the bar the rich young Durbanites have become very drunk, very quickly.

They lurch through and beyond each other, engaged in gauche, passionless sexual negotiation. In the news, when President Botha has finished speaking, we learn that ‘The Cosby Show’ is South Africa’s favourite television programme.

We are in South Africa because of the rugby tour. In New Zealand the debate about apartheid, expressed around the issue of whether we should send a national rugby team to play with those who practise it, has polarised New Zealand more than any other issue in the country’s recent history. This debate, accompanied by street marches, demonstrations and violence when tour times come around, has continued for a quarter of a century, with no solution. Its protaganists have vilified each other, taken to each other with clubs, fists and stones. The Government of the day has sent in flying squads of police with military backup against its own citizens. Elderly, respectable citizens and young people alike, protesting the nature of the relationship with the white South African community, have been injured and jailed.

The prospect of travelling to South Africa in 1985 to be there at the same time as a New Zealand rugby team raised a number of problems. On moral issues the media in New Zealand tend to lead from the rear. They and the politicians generally content themselves with a few vague denunciations of apartheid and leave it at that. Their sentences begin with: “We don’t believe in apartheid, but . . . . ”

Apartheid seems to produce a cowering in the New Zealand community (a relative perhaps of our cultural cringe?). As with the media, most people are happy enough to say they are against apartheid, and leave it at that. The fact that apartheid is such an important issue in New Zealand that it is able to effectively split families and friends and communities is not closely examined.

Newspapers and the broadcasting services scatter before the implications of this uniquely South African system. They tend to rely on notions of impartiality or balance or objectivity. It works this way: if someone makes a statement against apartheid then a defender of apartheid is called upon to offer a rebuttal. Such an approach is valid, but when it is constantly starved of context it becomes meaningless. Apartheid has been condemned in world forums by successive New Zealand governments for over twenty years for the reason that it is a travesty of almost everything we say we believe in. We believe in majority rule, we say we deplore structures of racial privilege, we speak out against economic deprivation, starvation, state terrorism, we speak out for freedom of movement, freedom of expression, freedom of assembly. All those things we say we believe in are inviolable rights of the individual. Apartheid is the most direct denial on earth of all those things, but for some inexplicable reason we find it necessary to qualify our disapproval by making excuses for it dressed up in mendacious language that has us offering “balance” or “engaging in meaningful dialogue”.

I am not saying that the proponents of apartheid should never be heard: they are heard very loudly in fact. They spend inestimable sums on being heard. Until recently they had official representation here. The free books they’ve given out in the thousands, all peddling that pervasive brand of reasonable-sounding propaganda, a judicious mixture of calculated truth and untruth, is on book shelves throughout the country, including in schools. And they have a high number of unofficial ambassadors and supportive organisations in New Zealand.

Equivocation towards apartheid has had the effect of paralysing journalistic responses to it. If the magical—and largely mythical—proposition of “balance” is left behind, then a journalist’s findings will have the effect of painting him or her into a corner. He or she will be labelled an anti-apartheid stirrer or pro-apartheid lackey. The name-calling obscures any genuine findings which the professional inquirer may come up with.

The prevarication also means that journalism in New Zealand cannot achieve the degree of excellence achieved by the world’s better newspapers, by reason of its reluctance to take a moral position. Thus, although the South African policy of apartheid has had a more direct effect on New Zealand society than possibly on any other outside southern Africa, the nature of the system has not, generally, been held up to tough public scrutiny by New Zealanders, despite all the sometimes excellent reportage that has gone on around it, especially around its disruption of rugby tours.

Polarisation of attitudes towards the issue raised the problem of how to cover the All Black tour. I decided eventually to look at the landscape of the tour rather than the tour itself. It meant following the tour itinerary but reporting on the communities through which the rugby pageant would be passing—following a kind of parallel path and perhaps never actually meeting with it. It may have been possible by such an approach to have caught a glimpse of why this foreign system has had the power to reach deep into the heart of the New Zealand community and have such a destructive effect on it.

The other reason for this method of coverage was that nearly all reporting on South Africa reflects a white view of black actions. No matter how sympathetic or how “balanced” it may be, it is still a white view leavened sometimes by remarks from a few black spokespeople. There is a whole set of implied cultural values in such reporting. Most foreign media in South Africa (and that is almost exclusively Western media) still tend to rely on a few white spokespeople to put the view of blacks, or they manage to cancel out the impact of their black reportage by qualifying it with comments from spokespeople for the white government. That is almost exactly the same thing as asking PR sanction for a journalistic inquiry.

What I hoped to do was simply to cut down on white interpretations of black actions and mostly confine myself to reporting what we actually saw and experienced along the way, rather than having it translated for me.

The ethnocentrism is to an extent inevitable, since blacks are unable to have a strong media voice. Most newspapers serving the black population tend to be off-shoots of white companies. The most notable liberal, even multi-racial, daily newspaper in South Africa, the ‘Rand Daily Mail’ was forced to close down in 1985, the victim of an allegedly purposeful squeeze on advertisers. (The Government openly expressed its pleasure at the closure.)

The squeeze purportedly came not directly on the advertisers but indirectly, via the ‘Mail’s’ owners and shareholders who said that the majority of the paper’s readers—blacks— were not worth aiming advertising at. Other newspapers are threatened by this. Proposed closures are described as being for economic reasons. Another example: in August 1985 the Anglo-American-owned Argus Company announced it was closing the 135-year-old ‘Friend’ in Bloemfontein (the only English newspaper and the only paper with a significant black readership in the area) and the ‘Sowetan Sunday Mirror’. A day later Argus said that it wished to retrench twenty-five percent of the staff of the ‘Cape Herald’, a twice-weekly paper aimed at Coloured readers in the Western Cape.

Anglo-American also owns South African Associated Newspapers, which published the ‘Rand Daily Mail’, and others including the ‘Cape Times’, which is reportedly under threat, and ‘Business Day’ which was established to lick up some of the cream left by the closure of the ‘Rand Daily Mail’ and which now, with a forthright editorial stance, is itself under threat.

The pressure against the press, however, has had a remarkable effect. There is a small, but vigorous and growing independent press, managed by journalists themselves, dedicated to increasing the flow of information throughout censorship-ridden South Africa.

What I hoped to do was simply to cut down on white interpretations of black actions and mostly confine myself to reporting what we actually saw and experienced along the way, rather than having it translated for me.

HOW COULD EVERYONE have been so wrong about Botha’s speech? That they were was evidence of an important fact in South African national life, and it sought to reinforce something I had been learning during our travels.

The major population divisions in South Africa are the Afrikaners, the English-speaking white South Africans, and those who are not white. There are of course scores of other differences, variations of race, colour, language and tribe—but no more so than in some other countries. The major dynamic in South African life is between those three groups. What is demonstrated time and again no matter how closely South Africans from those groups may associate from day to day, there is very little real intimacy between them. There is not even a great deal of factual knowledge about each other, although there is a lot of assumed knowledge.

It has its parallel in New Zealand with relationships between Maori and Pakeha. There is an easy familiarity in many places, the pub or the workplace most frequently, but real knowledge of each other is limited.

The group which expected change from Botha, which demanded it and loudly anticipated it was the white English-speaking population, or sections of it. It is these people who in the South African context tend to reflect the kinds of cultural, liberal values of the centre-right which have their roots in Europe. Thus their expectations tend to rebound back and echo in similar cultural environments, Europe and North America for the most part, but in Australia and New Zealand as well. It was from these places that the loudest expressions of disappointment came at the President’s speech.

The same degree of expectation was not apparent within the black population. Indeed I had been learning in the preceding few weeks just how low were black expectations of white society. I had not spoken to a single black leader, journalist, businessman, worker, whatever, who held the slightest expectation that President Botha’s speech in Durban would change anything. On the other hand, one would think from reading the English-language press and its foreign counterparts, that the Second Coming was at hand. (Botha himself during the speech referred to a “crossing of the Rubicon”, and his speech became known, with some derision, as the Rubicon speech.)

One black leader who had some hope for the Botha speech, however, was Bishop Desmond Tutu. When I remarked on the fact to him later during a meeting in Johannesburg he quoted Alexander Pope: “Hope springs eternal. . . .”

Botha’s speech was in fact a turning point of a kind for Bishop Tutu. He was shocked by what he saw as its mean-spiritedness. “It was a party politician trying to please the party faithful to ensure they would not lose these coming by-elections.” The Bishop and the President had in the preceding couple of weeks been engaged in a kind of pas de deux over whether they would meet to discuss South Africa’s problems. The President would not agree to see the Bishop alone, but he would agree to see him as a member of a large delegation of church people who were becoming increasingly perturbed at the breakdown of order throughout the country. He set conditions however: Tutu must renounce violence and he must renounce civil disobedience.

The Bishop was able to comply with the first condition—it has been a test of his leadership on many occasions—but he could not meet the second: “I said look, not on your life. I mean, how then are we going to be able to campaign against this evil system non-violently if it is not by disobeying unjust laws? I said sorry, I can’t go.”

How do you have a dialogue, Tutu asked, with nine people in the church delegation and who knows how many on Botha’s side? “There is no engagement of minds, no dialogue. I was hoping that in a one-to-one situation we would be South African speaking to fellow South African, a Christian to a fellow Christian, and maybe a grandfather to another grandfather. And because we wouldn’t have an audience to be posturing to, maybe a Damascus road experience could have happened.”

The Bishop was reported in the press to have snubbed Botha (The Bishop and the President finally met in May 1986).

The President’s speech in Durban appeared to offer Tutu final confirmation that violent confrontation was inevitable. A central premise of the speech was of white military unassailability with its twice-repeated threat, “don’t push us too far”. As if, somehow, we all still live in a world where justice can be decided by firepower.

The Bishop sits in his shirtsleeves in his Bishopric in Johannesburg (Tutu is now Archbishop of Cape Town), where, technically, he has no legal right to live. Under the apartheid laws even the Bishop of Johannsburg is forbidden from living in downtown Johannesburg if he is black. Tutu pays scant regard to that law, he will not carry a pass and he does not ask permission to be where he is, although he does have a house in Orlando township in Soweto to which he repairs from time to time. Downstairs his waiting room in the Bishopric is filled with government and church representatives and journalists from around the world. His telephone rings: “Where are you calling from? Germany? I’m on skids here, you’ll have to talk quickly my friend. . . . ” He puts a hand over the mouthpiece, and presumably while listening to his German caller says: “P.W. [Botha] says that the policy is not apartheid, the policy is reform. What that means is that the guy who is strangling you is not strangling you as viciously as you thought he was.” On the wall of the study is a batik of the crucified Christ, a copy of the Sam Ervin Free Speech Award for 1985, and a photograph of more than 400 clerics, including Tutu, at the Lambeth Conference of 1978. On his desk lies a copy of Leonard Thompson’s ‘The Political Mythology of Apartheid’ and two volumes of ‘For God or Caesar’ by R.G. Clarke.

Paton writes that in the world in which he grew up one did not lie or cheat or feel contempt for people because they were black or poor or illiterate. Justice was something that had to be done. Fiat justitia et perea mundus. Let justice be done though the world perishes.

The theme of God or Caesar is Tutu’s motivating self-reference. He quotes as fluently from history as he does from the scriptures. The Afrikaners, he says, haven’t read history. He quotes Huxley: “We learn from history that we don’t learn from history.” And Botha, he says, should know “that anyone who seeks to take on the church—anyone—ends up biting the dust, ignominiously. Think of the Neros, come through to Hitler, the Amins, the Bokassas—all of those guys who at one time thought they were almost invincible . . . they wanted to control the church, and, poor people, they ended up being the flotsam and jetsam of history.”

From South Africa, amidst all the violence, deprivation of liberties and killing, the preoccupations of New Zealand with its rugby tour seem very small and far away and unimportant. Even so, Bishop Tutu is still moved to uncharacteristically harsh language when reviewing the tour possibility: it was “an obscenity” to be preoccupied with “gambolling on our sports fields at a time when our people are dying”, or, “Your Mr Blazey was able to say ‘well, the unrest is in the black townships’, as if that justified his being able to come. I actually found it nauseating.” His contempt was expressed as strongly when a group of rugby players left New Zealand furtively to play “rebel rugby” in South Africa during May and June 1986.

To black South Africans, the intended rugby tour was not a central event. “We have far more serious issues to deal with,” Tutu says. To white South Africans, however, to the Afrikaner community in particular, and to many white New Zealanders, the tour was of central importance.

It so happened that I was already in South Africa when the New Zealand Rugby Football Union, following a court injunction against it, accepted that the tour was no longer possible. The cancellation was a huge event in New Zealand of course, and for a day or two it was possibly the most significant event in the life of white South Africa as well. Certainly, and although people throughout South Africa were being killed, burned, bombed and blasted, newspaper headlines were preoccupied with the thwarting of the rugby tour. If anyone had been in any doubt before, the strength of that reaction should have alerted them to the political importance of the tour to white South Africa. And despite all proof to the contrary, the cancellation was widely regarded as a hostile political act by the New Zealand Government, notwithstanding the fact that political persuasion—including a rare, unanimous New Zealand Parliamentary resolution passed against the tour—had been conspicuous by its failure. It ignored too the fact of the New Zealand Prime Minister’s touring African front-line states a few months earlier with the message—courageous in the circumstances—that his Government would not act to stop the tour: it would bring pressure against it, as per the Gleneagles requirement, but would not stop it. People believe what they want to believe almost exclusive of reason, even integrity, and in New Zealand that has never been more true than during the debate over sporting contact with racially-selected South African sports teams.

The mistake of assuming that priorities are the same the world over bedevils debate constantly, including the tour debate. I remember my disappointment at a speech given in 1981 to the National Press Club in Wellington by James Reston of the ‘New York Times’, a man whose work I had long admired. It was the year of the tour of New Zealand by a South African rugby team, a tour which produced civic violence and recrimination probably unmatched in New Zealand’s modern history. In response to a question Reston remarked sarcastically that if all that America had to worry about was a rugby tour, then there wouldn’t be much for America to worry about. One of my minor idols had just toppled himself. It was hard to believe that he had missed the point so completely.

When I met Bishop Tutu in Johannesburg we agreed to avoid talking about the motivations that might underlie support for the tour as well as opposition to it. But it was not hard to accept that it had very little to do with rugby as such. It seemed to me then, and still does, that people who are happy to use rugby to express the qualities they admire about themselves, must also accept that they have granted the rugby symbol converse power—that is, to express qualities in themselves that are not admirable. You can’t have one without the other.

Perhaps the person whose outlook has helped clarify the tour debate in my mind more than most is South African write Alan Paton. The major dilemmas he sees in his work and national life range between what he calls the greater and lesser moralities. It is a process of choosing between courses that are right. Great issues are rarely a simple matter of right or wrong.

Paton writes that in the world in which he grew up one did not lie or cheat or feel contempt for people because they were black or poor or illiterate. Justice was something that had to be done. Fiat justitia et perea mundus. Let justice be done though the world perishes. The greatest offences were not murder or theft or adultery, but coldness and indifference, a lack of concern about what happens to others: “that callous quality that the English language expresses in inimitable fashion in ‘I’m all right Jack’.”

Those people who support the rugby tour are correct when they say they have the right to play against whomsoever they wish, whenever they wish. And it is a right worth fighting for if it is threatened. Opponents of the tour say there are rights that take precedence over the exercising of the right to play rugby. And they too are worth fighting for.

Paton says: “If someone were to ask me, ‘what would you and your wife do (in South Africa) if you had young children?’ I would answer—we would have two choices: to stay here and give our children a father and mother who put some things even above their own children’s safety and happiness, or to leave and give them a father and mother who put their children’s safety and happiness above all else. Which would I choose? They are both good courses, are they not? I hope I would choose the first.”

VERNON WRIGHT / 1987