texts

2014-08-21

‘Stopover’ book introduction, Bruce Connew, August 2007

“At the time George Speight and his co-conspirators embarked upon the 2000 coup, taking hostage the Indian-Fijian prime minister, Mahendra Chaudhry, and elected members of his government, my two elder daughters in New Zealand both had Fijian partners.”

THE AGED PHOTOGRAPH on the preceding page is of two Indian-Fijian men. They are most likely early descendants of indentured Indian immigrants brought to Fiji between 1879 and 1916 to cut sugar cane on unforgiving, five-year contracts; or perhaps one of them is an indentured Indian immigrant, and out of indenture given the likely date of the photograph, holding hands with his son. No one is quite sure. I came across it loose inside the back cover of Aren Kumar’s family photo-album. I hadn’t been looking for photographs from the past. I was after recent snapshots of Aren’s relatives, especially those who had emigrated to such bright lights as Vancouver, Sydney and San Francisco since the coups in Fiji in 1987 and 2000. As I thumbed through the album’s pages, there were plenty of colour prints to choose from, sent home proudly as evidence of settlement from family members now in new countries and placed with care as pictures of aspiration; and not only in Aren's family album, but also in those of others in the valley. Emigrating was the big thing, and, in and out of earning a small living, still is.

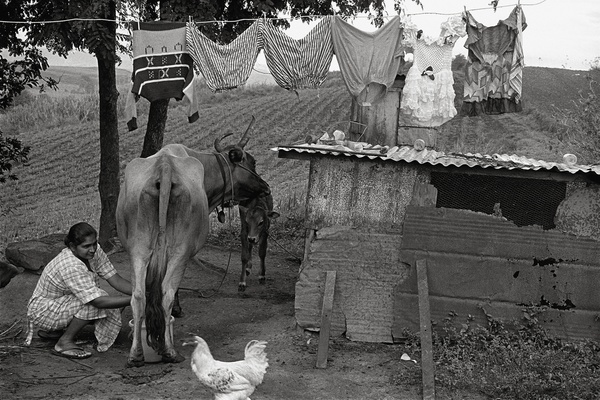

I had been staying with Aren’s younger brother Dharmen, a short walk up the dirt road that ran between their tall, abundant sugar cane crops. I had returned six times to Vatiyaka since the 2000 coup, each time lodging in a back room of the home Dharmen shares with his wife Padma and their two young boys, Kushal and Koonal. When I was first introduced to Dharmen in the midst of the coup, he was sirdar of his local sugar cane cutting gang. The gang was made up of men, mostly from his extended family. Like him, they lived, and on the whole still do, near one another on leased 10-acre sugar cane plots in Vatiyaka, a valley in the west of Viti Levu, Fiji’s biggest island. Each sugar cane season, by means of a proper arrangement, the men of the gang harvest one another’s crops. Aren owns the lorry that hauls the cut sugar cane to the mill.

Later, while settling in between the concrete block walls of my motel room, I see Chaudhry and a cluster of hostages briefly on television pacing up and down a path next to the building where they were routinely confined. It is unexpected.

At the time George Speight and his co-conspirators embarked upon the 2000 coup, taking hostage the Indian-Fijian prime minister, Mahendra Chaudhry, and elected members of his government, my two elder daughters in New Zealand both had Fijian partners. I hadn’t thought this so extraordinary, but with news of the coup, I began to think: how do I deal with this? One is an Indian-Fijian who arrived in New Zealand with his parents in 1987 after the previous two coups — the Rabuka coups — and the other an indigenous Fijian here on a university scholarship. They were almost as dear to me as my daughters. They got on well, and in fact once lived not far from each other in a middle-class suburb of Suva. But when we sat around the table talking after Speight had stormed parliament, it brought to mind other conversations we'd had. I could remember thinking during some of those conversations that each of them was describing a different Fiji, a different country almost — two countries called Fiji.

A week after Speight sets free the last of the hostages, I will watch my second daughter’s Fijian partner caress her temple as a contraction takes hold. Before morning, they will have had a son, my first grandchild, a boy, the first boy of the eldest son, a half-caste, ‘the boss’, says his Fijian grandfather. The next day, the Indian-Fijian partner of my eldest daughter will sit on the edge of the hospital bed and hold the swaddled baby close to him as he reads the front page of a newspaper.

I was keen to look around these countries, I had told them some weeks earlier. My plan, I said, was to be back in plenty of time for this birth. My reason for being in Fiji was no more than that.

After two days in Fiji, the parents of my second daughter’s partner invite me to the funeral of a paramount chief on Bau Island, an island potent well beyond its few indigenous hectares. It is the seat of the Vunivalu, the king of Fiji, except there hasn't been one for 10 years or more, not since the last died in November 1989. They loan me a school history book, so I'll better understand the weighty significance of Bau. It is day 39 of the coup. They tell me to photograph the ironies at the funeral, and I wonder how do you photograph ironies, and which are the ironies? I must look at the mourners, they explain. I flip back to the names given me the previous evening: tribal enemies, family enemies, political enemies, business enemies, and some of them, all of these at the same time. Bickering bitternesses, dark histories. It's so convoluted that rather than unravelling the detail of power, the plethora of opinions only pulls the knot tighter. Perhaps it is my imagination, but there is a smell in the air, on this day of farewell, of unclean affiliations and shifting powers. An unlikely mix of people, here from all over the country, will whisper not a word of the squalor consuming Fiji. They will enter the church, heads bowed, and sing as one ‘The Sands of Time are Sinking’, ‘The Lord is my Shepherd’, and ‘Now Praise We Great and Famous Men’.

Later, while settling in between the concrete block walls of my motel room, I see Chaudhry and a cluster of hostages briefly on television pacing up and down a path next to the building where they were routinely confined. It is unexpected. Any view of the hostages has been rare. Chaudhry walks separately from the others and appears meditative. It is sickening. Gazing back to this time, I figure it is then, at a moment of witness when Fijians are seen to hold Indians hostage, that I resolve to move on from the curse of dishonest power. A five-hour bus journey takes me across the top of Viti Levu to the sugar cane fields of Ba, the grassroots of Chaudhry’s support, where he was born in the midst of the unfortunate history of Indian indenture.

George Speight and his small band of army mutineers held their hostages for 56 days. While some said the coup concerned race issues, as time moved on, there was more talk of greed and a spiteful tilt at power. Whatever explanation will finally emerge, the several coups, including this Speight fiasco, have persuaded Indian-Fijians — who, third-, fourth- and fifth-generation Fijians, are forbidden to own land in Fiji — to suppose their future lies beyond the country of their birth. It is hardly unexpected that educated Indian-Fijian youth have aspirations, as their parents have for them, well clear of cutting sugar cane. And while the Fiji sugar industry has long been the sweet asset of Fiji’s economy on the back of Indian labour and farming flair, its influence is certain to decline. The migration of Indian-Fijians to first world countries continues.

Speight was convicted of treason and condemned to death, a sentence quickly commuted to life imprisonment. Chaudhry’s government was not reinstated when the army finally moved to end the crisis. Instead, the army leader, Commodore Voreqe Bainimarama, prescribed an interim civilian government and a new election. The Fiji Labour Party, Chaudhry’s party, failed to win that election, and nor did it win the following election in May 2006. At that time, people — amongst them high-ranking Fijians — were still, although unhurriedly, being brought to account for their part in the 2000 coup. There are more yet to be rooted out, some of whom were members of the May 2006 government when, on 5 December 2006, it was ousted by the army in the fourth coup d'etat in 20 years — the Bainimarama coup. A coup is a blunt instrument, even when bringing down an elected government deserving of not much compassion. It is unfortunate that Pacific leaders New Zealand and Australia, during the years since the Speight coup, failed to sufficiently encourage fitting governance out of Fiji’s elected administration.

This old photograph caught my eye because I had seen very few photographs of the sugar cane cutters’ forebears. I figured it must have been taken in the 1940s, perhaps earlier, and wherever I went in the valley, I asked about other such photographs, but there seemed none to be had. In conversations with the elderly of Vatiyaka, I endeavoured to establish far-off family lines, but it was rare that someone could help me. This knowledge seemed unavailable, as if their roots had withered from distraction. The children of the valley and their parents, some of them, could name the early ships that brought Indian indentured labour to Fiji to cut sugar cane, but I was told they had learnt this at school and not through the oral handover of family history. A woman in the valley explained that the early immigrants from India were largely uneducated and could neither read nor write. They soon lost touch with family across a sea of impossible distance. I asked Aren who these two men were. He couldn’t tell me, and neither could Dharmen when I borrowed the photograph to ask him. No one else could either. They were kin, Dharmen and Aren both said, but they couldn't fit them in. They were unknown.

BRUCE CONNEW / 08.2007