texts

2014-08-15

‘Suburbs’, Bruce Connew, November 1995

“Another billboard in the near distance, a different shape from the first, said BEST MEN SMOKE BEST BLEND. And you looked past it to a landslide of shacks.”

Suburbs

OBED ZILWA, a photographer from the Cape Town Argus, rang our cellphone (South Africa had had them a month) and we arranged to meet in a few minutes, on a central city street corner.

“Where is it from here?”

“One robot, turn right, go straight; third robot turn left; go straight fourth robot, wait on that corner.” His voice was musical.

We knew that robots were traffic lights but not that directions were given in accumulating robots from the starting point. Twice, Obed returned to his office and telephoned to ask where we were. He would be my guide through the camps.

On the other side of the fine, four-laned motorway as you drive into town from Cape Town’s international airport, there are squatter camps. They sprawl just off the motorway’s edge out to the horizon. It was a shock. I had forgotten about them. Last year, they were trying to fence them off just high enough so you couldn’t see in from your car.

Cape Town hopes to have the Olympic Games in 2004. There’s a plan to clean up the misery yet to provide only basic facilities—sewerage, water and electricity—to the millions who live in these and other camps and townships will cost billions of rand. The Olympics won’t come cheap either, and you have to wonder whether an elegant stadium will take precedence over small brick houses with facilities. I was travelling with Gordon Campbell, on assignment for the New Zealand Listener magazine to cover South Africa’s first democratic election. The country was teeming with the world’s news media. Some of the faces were familiar from my last trip nine years before. At any given event, they would disappear around three in the afternoon to write stories and send pictures to meet deadlines about the globe. It was a surprise, sometimes, to read their accounts of an event at which I was present and see an interpretation of the day that was different from mine. Presumably, when you watch CNN or the BBC, read Newsweek, Time or Stern, it’s still the same.

Obed looked like a photographer. He had on one of those sleeveless khaki jackets with all the pockets, even a pocket at the back with a zip. “Don’t drive into Khayelitsha, just wait on the bridge” he said. “You don’t want to get lost in there.” Obed lived in a small “middle-class” section of Khayelitsha and had been stabbed four times while taking photographs in the squatter camps, mostly by people thinking he was a police informer.

I parked where he said on the bridge over the motorway and waited for him to arrive. It was a place where people came and went, welcomed and farewelled by a LION lager billboard that said in huge type, RICH & GOLD. While I sat in my locked car, passengers shuffled off a double-decker bus and walked slowly over to taxi vans that took them into Khayelitsha proper. Soldiers were there, too, in an army ‘hippo’ just over the bridge, watchful like school prefects. It looked controlled and ordered. Yet, I felt uneasy. Another billboard in the near distance, a different shape from the first, said BEST MEN SMOKE BEST BLEND. And you looked past it to a landslide of shacks.

Obed got into the car. He locked the door behind him and sat a bulky camera bag on his lap. He was in his mid-twenties, a happy man with occasional serious turns. He rolled the car window down no more than two finger widths and said, “From in here, this is how you talked to them out there.” He was on home ground. I believed that, faced with trouble, he would be utterly reliable.

We drive—very quickly—past shacks that have the attachments of settlement: curtains, fences, careful paint jobs, as if those squatting understand this is their one option and make the best of it. It’s at once uplifting and crushingly sad.

We stop to photograph a young girl—or is it a boy?—carrying a white doll, life size, and with one arm missing. The child runs away into a corrugated-iron shack, which is painted bright pink with a sky-blue trim at the base. People stop to look. We keep moving.

On Obed’s advice, I take some MANDELA—THE PEOPLE’S CHOICE posters from the boot of the car and sit them across the rear window tray. “When we’re out walking, they’ll think it’s an ANC car and leave it alone,” he says. We stroll into the narrow, sandy pathways between shacks, Obed behind me always. There is intricate wrought-iron work forming gates and security windows. We must be crossing private property, or at least neighbourhood territory, but no one checks our walk. Obed passes the time of day with some of the locals. They’re keen to know what’s happening and one old man, drunk on corn liquor, shouts, “All Blacks! All Blacks!” We all laugh.

Through a shack door, open in the heat, I glimpse the most unexpected wallpaper. Printer’s sheets of can labels: fruit cocktail, halved pears, apricots in rich orange with slashes of blue, right up the walls and across the ceiling, placed with the rough care of student wit. But this was a family home. Uplifting again. Would they have giggled? Obed asks whether I can photograph inside. Yes, I can, they don’t hesitate. After the photographs, it doesn’t occur to me to ask, why this wallpaper or where it’s from. Or even to talk. I smile and nod an inadequate thank you.

And then a green shack, squat in a patch of sand with a garden painted yellow on its walls. Do you laugh or cry?

Round the next corner there is more. LUX soap packets offset with a ceiling of coffee jar labels. And the Mandela poster that protects our car is here on the wall amongst the repeating images of the Hollywood LUX woman. There is a small television—I can’t recall whether colour or black and white—run off a Bosch car battery.

Moving from shack to shack, I discover further fruit cocktails, green this time, and pear halves, a living room of supermarket junk mail, again carefully aligned, kapow! with colour and design. Is this a neighbourhood thing or is it throughout Khayelitsha and the other squatter camps? I have no idea and neither does Obed.

And then a green shack, squat in a patch of sand with a garden painted yellow on its walls. Do you laugh or cry?

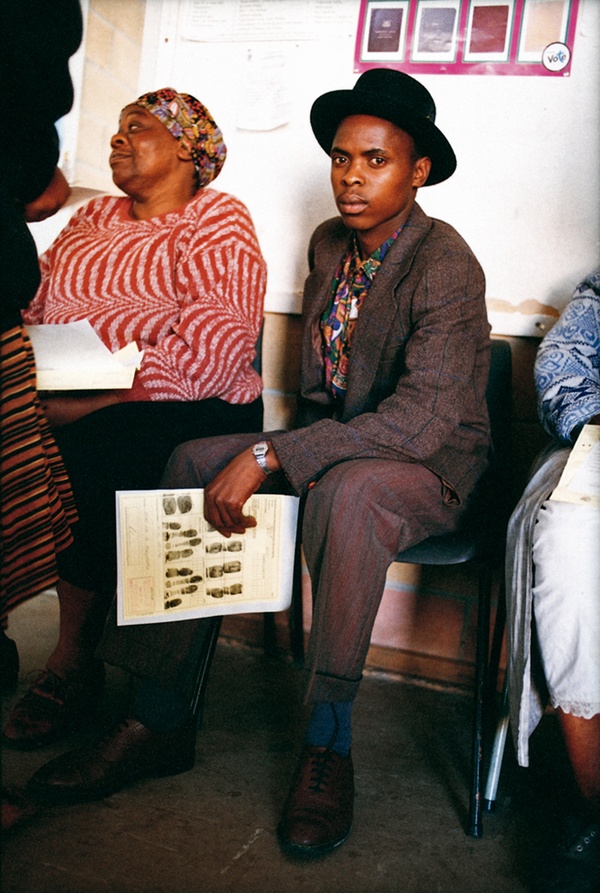

Obed needs to register to vote, so we head off by car to Khaylitsha’s community building and a queue a kilometre long. People wait patiently to be fingerprinted, hot from the sun, standing alone, silent or in groups, chattering and laughing. The entire black nation—voting for the first time, it is they who need to register—are required to be fingerprinted. Millions upon millions. It’s extraordinary. On a yellow A4 sheet of light card, they place each finger in turn and then the thumb, both hands and then a paw print of the four fingers of each hand together. It’s thorough. There is a bucket off to the side where you can wash the ink from your hands. I photograph Obed registering and later send him some small work prints.

We pull up at a throng near an ANC-run voter education stand on a road bordering Guguletu, a squatter suburb adjacent to Khayelitsha. Five young men and women are handing out leaflets and large sample ballot papers. There is lots of noise and excited banter. Quite suddenly they grab their literature and bound into Guguletu, past single men’s hostels towards the central market-place, thrusting posters and brochures at everyone on the way. At first, Obed runs with me as we follow but Guguletu, he says, is a PAC stronghold and there could be trouble. While I continue, he hurries back to the car, and brings it to the market, parking it face out and ready for a quick exit.

Obed leaves his camera bag on the floor of the car and stays close behind me wherever I move. Thieves and knives, he says. I photograph a hard-boiled egg seller who carries a salt dispenser.

We move onto Crossroads and find some girls in bare feet skipping on open stony ground. Obed squeals with delight as I join in the skipping; using a wide-angled lens, he photographs me. He wants to put the photograph in the Argus. I don’t know whether it did go in but he gave me some prints the next day.

BRUCE CONNEW / 11.1995