texts

2022-11-07

Ghosts, NZ Listener magazine, 16 October 2000

Bruce Connew entered Kosovo 19 June 1999, a week after Nato troops, and hitchhiked around for eight days. He discovered a need for people to show evidence of the outrage, and to tell their stories.

When I awake this morning, alone in Musa Kameri’s house, before anything else, my eyes lock on a fussy gilt picture frame hanging neatly on the plastered wall at the end of the bed. There is no picture in it, just the frame. I take a photograph of it, and wonder where the picture has gone, and who has hung it empty?

Later, I learn that the frame had contained a tapestry of a Kosovo landscape, hand-stitched by Musa’s mother. He had found the empty frame strewn on the floor amongst left-overs from the looting and vandalism.

At breakfast, Musa produces two passport photographs of a father and son. He had discovered them in a packet, on his return to Kabas, a village in the south-east of Kosovo, beneath the shambles covering the lounge floor of his parents’ ransacked home.

“They are Serbs”, he says of the photographs. These are the people who had made themselves at home in his parents’ house during the war, and spitefully trashed it.

Up the road from Musa’s house, there is more evidence of Serbian occupation. A refrigerator lies belly up on the grass beneath the balcony of a house from whence it came, along with a collapsed couch and lounge chair, a shattered television, and goodness knows how many other smaller domestic objects littering the yard, heaved in one, big, foot-stamping temper tantrum. Graffiti is daubed everywhere: SERBIA TO TOKYO and SEX. As a grotesque joke, the occupiers had wound red and white plastic police tape, criss-crossing through broken windows and trees, from out-buildings to the dismembered satellite dish, and back again. Inside the house is the same. Graffiti and ruin. Whoever did this has toiled with resolve.

In an upstairs bedroom, I come across a small gallery of snapshots of teenage girls collected from houses about the village, and pinned to a wooden wall above the bed where a Serb soldier slept.

Near Ferizaj, there is a padlock on the double gate to Barazan’s cemetery, forcing us to scale the fence. Once inside, we walk deliberately to the grave of fifty-five-year-old journalist, Hakj Braha, editor of the daily newspaper, Bujku. Hakj, whom the Serbs arrested, tortured and executed, is indistinct in his bed of wet dirt at the bottom of the freshly opened grave. There is no coffin, and I can make out his hair, possibly an arm, maybe his legs pulled up, half akimbo. Those of us that move forward, lean in awkwardly, our feet back from the lip of the grave, fearful the edge may give way and thrust us in on top of the putrefaction.

Beneath a tall hedge on the other side of the cemetery, a wide mound of earth marks the batch burial place of five people. I step in this direction, through the long grass of the cemetery, last in line of the single file, fearful that here is a witty setting for a frustrated and retreating army to lay mines. The two men first to the grave pull back a weathered concrete block and squat to remove a capped shampoo bottle containing a note. We crowd round as one of the men uses a grass straw to encourage the rolled paper note free, and listen to him explain its message. The widow of one of those buried here has written her husband’s name.

Yesterday, at the cemetery, Teuta Haxhimusa, a KLA interpreter, had pointed out the grave of her friend, Adriana Abdullahu, who had been shot and killed two days before the bombing began. A fledgling actor, she had finished her night on stage and was relaxing with friends over coffee in a Pristina cafe, when a burst of gunfire raked the patrons. Adriana took two bullets, one in her lower left arm, and the other, the one that killed her, through the side of her neck.

This morning, I meet her mother. Before long, we are seated around an outside table in the mid-morning heat, waiting to be served Turkish coffee, while Jalldeze pulls photographs of her dead daughter from a plump wallet, and scatters them in quick succession all over the table: a portrait, with friends, with her mother, in London with her sister who is an interior designer, on stage, in her coffin wearing a wedding dress because she was unmarried. Jalldeze disappears inside and returns with her daughter’s coat. She puts it on to show me where the bullet that killed Adriana went through the collar.

Back on Ferizaj’s General Tito Boulevard (street names will change across Kosovo, I’m told), I pass several children separately selling a few packets of cigarettes off cardboard boxes on the footpath, before noticing, set up in front of a blown out building, a small table with items for sale: two tins of nugget, a baby feeder cup, a comb, a shaving brush and a tea strainer. Three women are sitting amongst the rubble, around a gas burner, heating coffee. They are a lawyer, a teacher and a dentist.

There are no telephones and no public transport. You can buy a cabbage, tomatoes, green peppers and cucumbers, and even a little petrol, through word of mouth. I lurch off again, unsure of my direction, but wherever I stray, no matter which street, I find someone wanting to reveal their detail of the defilement of this country. Show and tell. A philosophy professor ushers me to his scorched home, the roof on the floor amongst the charred pages of his 2000 books. The old couple next door offer me water and a look at their despoiled living room and bedroom, torn family photographs on the floor, old black and white ones, along with every ornament they ever had. And there are those empty picture frames. Every household is mopping up, at least those who still have a home to mop. Rugs hang off every balcony. Vacuum cleaners and brooms, dead dogs, children playing war in the street. Burnt home after burnt home, demolished shop after demolished shop. A KLA amputee makes me promise to send him a photograph. But how can I? There is no postal service. I go by youngsters and early teens cavorting, in groups, with American Nato troops, and wonder at the likelihood of half-American babies. A man has his daughter re-hang a rope with a noose at the end from their balcony to show me how he found it on his return. In the garage, a Serb torture chamber, he says, he unfolds a Turkish rug to show me wads of clipped hair. A double-twisted length of heavy wire. He found much blood here. If this detritus can serve as some form of corroboration, then it surely was a torture chamber. I try not to believe it all, but it’s difficult. It’s easy to see a torture weapon in every object. Black Serb logos crudely highlight the white end wall. The way I figure it, if only half of what I’m learning and noting is accurate, what has happened is an outrage. The owner of a disembowelled camera shop offers me a ride twenty kilometres to Kacanik to see a mass grave. The long, shallow grave has been partially dug up and the bodies re-buried in two rows. The marker pegs reach 68.

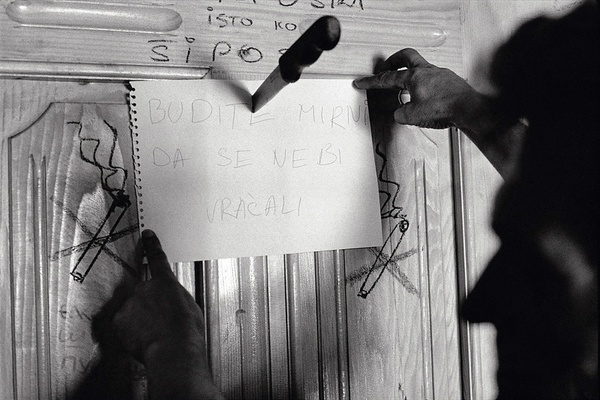

The next day, the uncle of an acquaintance locates a couple of litres of petrol and we head off to Sojeva, a village ten minutes from Ferizaj, past blackened and bullet-pocked homes on the way. One double-storeyed house, with a caved in roof, displays, on its front wall, a mammoth mural of what looks like the Garden of Eden. Sojeva is all but empty. The one man we find, after repeated shouting, takes us by a bleached skeleton, neatly assembled, in the dead embers of a levelled house. Two nights before, he had wheelbarrowed three dead men from the village to a field nearby and buried them against a hedgerow. He shows us a house with a hand-written note stabbed to an inside door: BEHAVE OR WE’LL BE BACK.

Shop mannequins are an indicator of the progress of the return. If they are naked, you know it’s very early days, and each town is different. This first afternoon in Prizren, the mannequins of a large clothier lie limp in the shop’s sun-bathed window, bare and disassembled. By next morning, they stand tall, trimly dressed, and their arms gesturing.

Tonight, people jubilantly jam the streets, making it awkward for German army vehicles to manoeuvre. A middle-aged man, with his wife, warns me to beware of Serbs up the hill behind the town; one or two might still be there. The press have housed themselves in the city’s one working hotel. There is a satellite TV van, outside on the footpath, with a notice, strung across its entrance, saying in English and Albanian: no telephone. Some Albanians have cell phones and I try to imagine to whom they will pay their bill.

In spite of this honeymoon interval between the end of war and the beginning of revenge, three Albanian youths can’t help themselves, and are caught looting by German Nato troops who snip their thumbs behind their backs with plastic ties. One complains that the ties hurt, but his concern should be for the jeering crowd pressing in. The German commander invites me to photograph them — ”we have your faces” — then releases them, and they scarper.

Not long after, on the road to the Albanian border, I spot a grey, speckled horse upside-down at the edge of the road, its legs spread stiffly in death. Further on, I come across a man pulling for all he’s worth on the bridle of a fractious horse, while his wife and another man push either side of a four-wheeled cart, and four children pile in with their personal possessions. I lend my weight as it begins to rain. They cover the cart with a UN plastic tarpaulin, as the rain becomes a downpour, and insist that I get up on the cart, undercover, while the men continue to push and pull. It’s a moment of generosity. An endless procession of refugees potter past, in all manner of vehicles, flapping their arms in victory, bent on repossession.

Peja (Serb, Pec) is altogether a different place. The two Greek photographers, whose car I have just climbed from, say goodbye, and half run in the opposite direction, surprised I don’t stick with them. By the time I understand this, they are in the distance. An old woman follows my progress from a third floor apartment. There’s hardly anyone on the streets. The destruction is manifest. I’m not feeling good about being here, and aim to move on, very soon, to Mitrovica further north. I spot a journalist in a gaudy yellow jersey, near the razor-wire-ringed headquarters of the Italian Nato troops. He advises me not to head north, not without a car, the place is smothered with very angry Serbs.

The owner of a mattress factory, Salih Devolli, takes me under his wing, and leads me to two blood-soaked rubber mattresses in the far corner of his main warehouse. Salih insists that this is a Serb torture site. We speed, in one of his several Mercedez, a little way out of town, to an articulated lorry on its side. A blackened arm stretches from the cab, its fingers chewed by dogs, and I can make out another body further in. The truck is chock-full with looted goods. Serbs. They’ve been there a week. The story goes, that the KLA shot them as they crashed a roadblock.

On the way back, I encourage Salih to a funnel of dark, rising smoke. It’s the gypsy quarter, and already 10 photographers are pursuing Italian troops slapping at the flames with blankets and sacks. Salih questions around, and tells me the gypsies started the fires to discredit the KLA. It’s hard to swallow, particularly when the Italians spread-eagle two, uniformed KLA soldiers against a brick wall.

The centre of town, where Salih drops me, is still shy of people, yet, before I’ve moved more than ten steps, a young man volunteers to show me a Serb sign painted large and evenly in the tiled squares of the path to his house. His home is burnt out, but it’s the sign he wants me to see first. We move on to four burnt out mosques.

Throughout the day, there are small popping explosions, and gunfire, that anyone you ask says, “Serbs”. I learn later from a man limping along a littered pathway that he was one of two Albanians wounded, the other seriously, when an elderly Serb dropped a hand grenade down on them from a first floor apartment. He pulls up his trouser leg to the medical patches on his calf. I witness an old man in a suit, clutching a suitcase, climb the rubble that was once his home.

A teenage boy walks quickly towards me in the evening gloom and I ask, with a gesture of hands, whether he knows of somewhere I can sleep. He beckons me to follow him up a dead-end lane to a grey apartment block, and we climb to his mother, Zilha Mavraj, on the fourth floor. They arrived this morning from Montenegro to a mangled home, and have moved into this apartment vacated by Serbs.

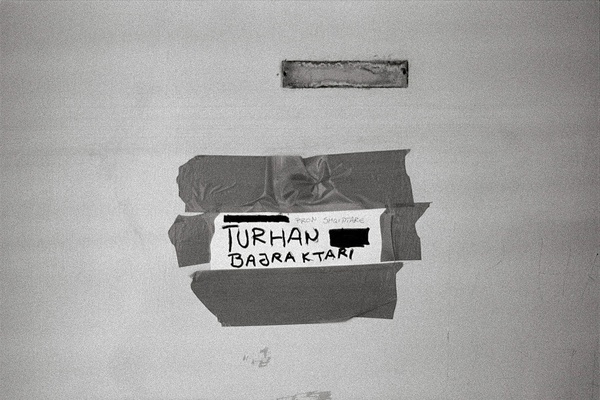

I stay two nights in this block, the second night in an apartment alone. I half expect the owners to walk in, and wonder how I will explain my presence. I feel like an occupier. Everything is in its place. Wedding pictures on the wall, towels in the bathroom, hats and coats, shoes, tooth brushes, hair gel, even curdled milk on the bench, as if the owners went to the shops, and never came back. The calendars in both apartments are turned to May, and it’s now near the end of June. I can’t bring myself to sleep between the sheets on the double bed. Who were these people? I can see their faces in photographs on the wall, but can find no names, no letters that may provide a clue. I’m reluctant to open cupboards in case of booby traps. I don’t even lift the telephone.

As I prowl around, I’m shunted back to the refugee camp in Macedonia where the uniformity of tents and circumstance gave me people, but no context, no clue as to who these people really were, clues that possessions provide. Here, I have the possessions, but no people.

BRUCE CONNEW / 10.2000

NZ Listener spread, 16 October 2000