texts

2022-11-10

Mr Arjun

... a story by Brij Lal

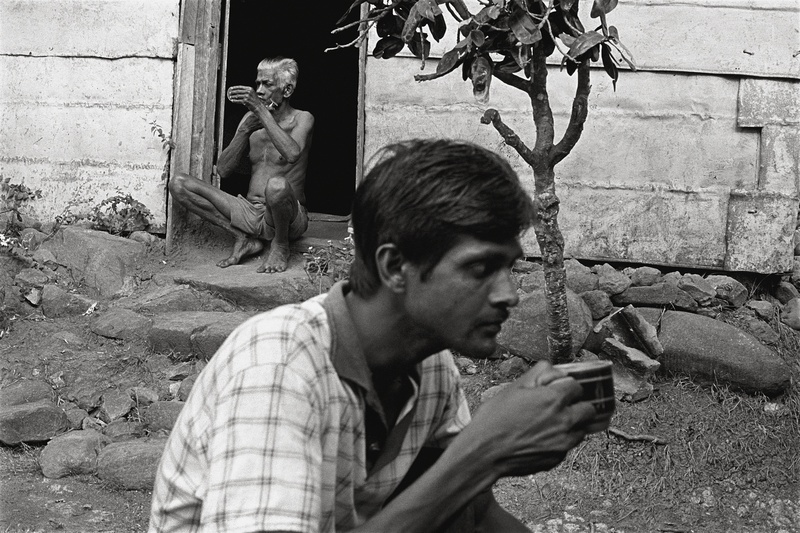

I seldom visit Tabia now, the village of my birth and childhood. The place is a labyrinth of memories better left untouched. But on the rare occasion I do, I always make an effort to see Arjun Kaka. Now in his late seventies, he is the only one in the village who has a direct connection to my father’s generation, the last link to a fading past. He knows my passion for local history and we talk endlessly about past events and people. Kaka is illiterate and a vegetarian and teetotaller. Everyone in the village knows him as a man of integrity, a man with a completely unblemished reputation. His wife died about a decade ago and he now lives on the farm with the family of his deceased son. The other three boys, bright and educated, migrated to Australia after the 1987 coups. He misses them desperately, for this is not the way he had wanted to spend his twilight years. He now wishes one of them had remained behind. There is no telephone in the house and letters from his children are rare. He wonders about his grandchildren, how old they are, what they look like, if they remember him, ruminating like old men usually do.

A few years ago, covering a general election, I went to Labasa and visited Kaka. ‘Why don’t you visit Krishna and the other two boys, Kaka?’ I said after he had mentioned how badly he missed his children. ‘At my age, Beta, it is difficult,’ he said sadly. ‘You know I cannot read and write. Besides, my health is not good.’ ‘Kaka, so many people like you travel all the time,’ I reminded him. ‘Look at Balram, Dulare, and Ram Rattan.’ Formerly of Tabia, they had moved to town when their leases were not renewed. Some had even gone to Viti Levu. Kaka nodded but did not say anything. Then an inspired thought occurred to me. I was returning to Australia a few weeks later and could take Kaka with me. When I made the offer, his face lit up, all the excuses forgotten. They were excuses, really, nothing more. He had a deep yearning to travel and see his children and grandchildren but not knowing how. ‘Beta, e to bahut julum baat hai,’ he said — this is very good news indeed, son. He embraced me. ‘You are like my own son. Bhaiya [my father] would be very proud of you.’ If truth be known, since dad’s death, I regarded Arjun Kaka as a father figure.

Once a rural backwater, Labasa was on the move. There was a time when going to Suva was considered ‘going overseas’, an experience recounted in glorious and often embroidered detail for years. Australia and New Zealand were out of the question. ‘The place is emptying day by day, especially since all the jhanjhat [trouble] started.’ He meant the coup. ‘There is no growth, no hope. Young people, finishing school, leave for Suva. No one returns. There is nothing to return to.’ ‘Dil uth gaye,’ Kaka said — the heart is no longer here. Kaka’s observation reinforced what I had been told in Suva. There was hardly a single Indo-Fijian family in Fiji which did not have at least one member abroad. ‘The best and the brightest are leaving,’ a friend had remarked in Suva. ‘Only the chakka panji [hoi polloi] remain.’ The wealthy and the well-connected had their families safely ‘parked’ in Australia and New Zealand, he had said. An interesting way of putting it, I thought, suggesting temporariness, a readiness to move again if the need arose. I had heard a new phrase to describe this new phenomenon: frequent flyer families. Those safely abroad talked of loyalty and commitment to Fiji, of returning one day, but it was just that, talk, nothing more. I felt deeply for people who were trapped in Fiji, victims of fate, living in suffering and sufferance.

As the news of Kaka’s planned trip to Australia spread, people were genuinely happy for him. At Tali’s shop the following evening, Karna bantered, ‘Ek memia lete aana, yaar’ bring a white woman along with you. ‘Kab tak bichari patoh tumhar sewa kari’ — how long will your poor daughter-in-law continue to look after you? ‘Learn some English words,’ Mohan, the village bush lawyer, advised. ‘Thank you, goodbye, hello, how are you, mate.’ ‘Make sure you are all “suit-boot” [well dressed], not like this’ — referring to Kaka’s khaki shorts and fading floral shirt. ‘We don’t want others to know that we are ek dam gawar [country bumpkins].’ ‘Which we are,’ Haria interjected. ‘Yes, but we don’t have to advertise it!’ Mohan countered. Bhima wondered whether some of the kulambar [CSR overseers] were still alive and whether Arjun Kaka might be able to meet some of them in Australia. Mr Tom, Mr Oxley, Mr Johnson.

Mr Tom: now, there was a name from ancient history. He was the first white man I ever saw. Tall, pencil-thin, white hard hat, his face like a red tomato in the midday sun, short sleeve shirt and trousers, socks pulled up to the knees, the shirt pocket bulging with pens and a well thumbed note book. The overseers had a bad reputation as heartless men driven to extract the maximum from those under their charge. Was that true, I wondered. ‘Well the Company was our mai-bap,’ Kaka said — our parents. ‘You did what you were told,’ Bhima chimed in. ‘The kulambar were strict but fair.’ So it wasn’t all that bad? I wanted to know more. Bhima continued: ‘As far as they were concerned, we were all the same, children of coolies. They didn’t play favourites among the farmers. Look at what is happening now.’ I had no idea. ‘Look at all the ghoos-khori [corruption].’ He went on to explain how palms had to be greased at every turn — to get enough trucks, to get your proper turn to harvest. ‘In the old days, if you did your work, you were left alone.’ Nostalgia for a simpler, less complicated time perhaps, I wondered, but said nothing.

People in the village had very sharp memories of the overseers. ‘Mr Tom drank kava like fish,’ Mohan remembered. ‘And chillies,’ Karna added. ‘A dozen of those “rocketes”, no problem. Chini-pani, chuttar pani.’ We all exploded. Chini-pani in the cane belt meant ‘sugar has turned to water’ — the sugar content is down, which is what the overseers at the mill weighbridge allegedly told the farmers, cheating them of a fair income. Chuttar pani refers to washing your bum with water after going to the toilet, a reference in this case to Mr Tom’s probably agonising toilet sessions after eating so many hot chillies. Overseers, I learnt, were expected to have some rudimentary Hindi because the farmers had no English. But sometimes their pronunciation of Hindi words left people rolling with laughter. Bhima recalled Mr Oxley once asking someone’s address. ‘Uske ghar kahan hai?’ — where is his house? But the way he pronounced ‘ghar’ — gaar — it sounded like the Hindi word for arse: ‘Where is his arse!’ Kaka recalled Mr Tom visiting Nanka’s house one day wanting to talk to him, but Nanka had gone to town. Mr Tom asked Nanka’s son whether he could speak to his mother. Instead of saying ‘Tumar mai kahan baitho’ — where is your mother [mai] — he accidentally added the swear word chod, to fuck, a common swear word among overseers: ‘Tumar mai-chod kahan baitho’ — where is your motherfucker! Which left Mrs Nanka tittering, covering her mouth with her orhni [shawl], and scuttling towards the kitchen.

This warm reminiscence of aging men brought back memories which until now had vanished. I recalled the excitement of the visit every three months or so of the CSR Mobile Unit coming to the village. On the designated evening, the entire village would gather in the school compound, sit on sheets of stitched sacks [paal], cover themselves with blankets in the colder months and watch a tiny screen with grainy pictures perched at the end of a Land Rover. At the outer edges of the compound would be placed a put-put-put droning generator to provide power to the projector. Sometimes, the documentary would be about a model Indian family, sometimes about some aspect of the sugar industry or good husbandry. ‘This is Ram Prasad’s family,’ the voice-over would announce in beautifully cadenced English. Then we would see an overseer, in white hard hat, his hands on his hips, talking to Ram Prasad, in short sleeves and khaki pants, his amply-oiled hair neatly combed back, his hands by his side or behind his back, not saying much, avoiding eye contact with the overseer. Ram Prasad’s wife would be at a discreet distance by the kitchen, wearing a lehenga and blouse, her slightly bowed head covered with an orhni, while schoolchildren, in neat uniforms with their bags slung around their shoulders, walked past purposefully. The moral was not lost on us. We too could be like Ram Prasad’s family, happy and prosperous, if only we were as dutiful, hard-working and respectful of authority as them.

Occasionally we would see documentaries about Australia. We did not understand the language, partly because of the rapid speed at which it was spoken, but the pictures remain with me: of vast golden-brown wheat fields harvested by monster machines, hat-wearing men on horseback mustering cattle in rough hilly country, wharves lined with huge container carriers, buildings tall beyond our imagination and streets choked with crawling cars. Pictures of parched, desolate land puzzled me. It seemed all so harsh to us surrounded by nothing but lush tropical green. I sometimes wondered how white people, who seemed so delicate to us, could live in a place like that. But the overwhelming impression remained of a vast and rich country. It was from there that all the good things we liked came: white purified sugar we used in our puja, the bottled jam, the Holden cars. The thought that we would one day actually live there was too outrageous to contemplate. And we did not.

I also remembered the annual school essay competition. The CSR would send the topics to the school early in the year. Usually, they were topics such as ‘Write an Essay on the Contribution the CSR Makes to Fiji’, or ‘How the Sugar Industry Works’. The brighter pupils in the school were expected to participate and turn in neatly written and suitably syrupy pieces. I was a regular contributor. One day during the morning assembly, our head teacher, Mr Subramani Gounden, announced that I had done the school proud by winning the third prize in the whole of Vanua Levu! The first one ever from our school, and the only one for several years, I was later told. I vividly recall trooping up to the front to receive my certificate

scrawled with a signature at the bottom. Such success, such a thrill. It was at university that I realised how unrelenting and tough-minded the CSR was in the management of the sugar industry, but at primary school we were immensely grateful for the tender mercies that came our way. We were so proud that on prize-giving day we had an overseer, no ess, as our guest of honour. Mr Tom was a regular and much honoured presence.

One day I asked Arjun Kaka what he thought Australia would be like. ‘Nahin Jaanit, Beta’ — I don’t know. ‘There must be a lot of people like us there,’ he said. ‘Why do you say that?’ I asked somewhat perplexed. ‘You know white people. They can’t plant and harvest sugar cane, build roads or do any other hard physical work like that. All that is our job. They rule, we toil.’ Kaka spoke from experience — very limited experience of the world, needless to say — but I assured him that white people did indeed do all the hard work in Australia. They planted and harvested cane and wheat, worked as janitors and menial labourers, drove trucks, buses and cars. Kaka remained unconvinced. ‘It must be cold there?’ he enquired. I tried my best to explain the seasons in Australia. Knowing the Canberra weather in summer, I said ‘Sometimes it gets hotter than Fiji.’ ‘But how come then white people there don’t have black skin? Look at us: half a day in the sun and we become black like baigan [eggplants].’ ‘You will see it all for yourself, Kaka,’ I said and left it at that. This old man is in for the shock of his life, I thought to myself. His innocence and simplicity, his complete lack of understanding of the outside world, was endearing in a strange kind of a way. I made a mental note of things I would have to do in the next few weeks: get Kaka’s passport and visa papers ready, ask Krishna in Sydney to purchase the ticket. Then I left for Suva, promising to inform Kaka of the date of travel well in time. I would see him in Nadi.

Kaka was relieved to see me again in Nadi. This was his first visit to Viti Levu, the first out of Labasa actually. In the late 1990s, the Nadi International Airport resembled a curious mixture of marriage celebration and funeral procession as people arrived in busloads to welcome or farewell friends and family. Men were dressed in multi coloured floral shirts and women in gaudy lehenga and salwar kamiz and saris. I noticed a family huddled in one corner of the airport lounge. One of them was leaving.

I could quite imagine the scene at their home the previous night. A goat would have been slaughtered and close family and friends invited to a party. The puffy red eyes told the story of a sleepless night. A middle-aged woman, presumably the mother, prematurely aged, with streaks of grey dishevelled hair, was crying, a white handkerchief covering her mouth. And the father, looking anxious, sad and tearful, was chatting quietly with fellow villagers, passing time.

This was a regular occurrence in those days: ordinary people, sons and daughters of the soil, with uncertain futures, leaving for foreign lands. What was once a trickle is turning into a torrent right before our eyes. To an historian, the irony is inescapable. A hundred years ago, our forbears had arrived in Fiji, ordinary folk from rural India, shouldering their little bundles and leaving for some place they had not heard of before but keen to make a new start. A hundred years later, their children and grandchildren are on the move again: the same insecurity, the same anxiety about their fate. No one seems to care that so many of Fiji’s best and brightest are leaving. Some Fijian nationalists actually want the country emptied of Indians. Kaka noticed my contemplative silence. He had read my thoughts. He asked, ‘Beta, desh ke ka hoi?’ — what will happen to this land? It was an interesting and revealing formulation of the problem. He hadn’t said ‘hum log’ — a communal reference to the Indo-Fijians. He had placed the nation — desh — before the community. I wished Fijians who were applauding the departure of Indians could see the transparent love an illiterate man like Kaka had for the country.

Arjun Kaka seemed nervous as we entered the plane: this was only the second time he had ever flown in a plane. The first time was when he flew from Labasa to Nadi to catch the flight to Sydney. Kaka was watchful, nervous. ‘So many seats, Beta,’ he said. ‘Jaise chota saakis ghar’ — like a mini theatre. Not a bad description, I thought to myself. ‘And so many people! Will the plane be able to take off?’ I watched him say a silent prayer as the plane began to taxi. ‘Everything will be fine, Kaka,’ I reassured him. ‘Yes, Beta, I just wanted to offer a prayer,’ he said smiling. Sensing my curiosity, he said, ‘Oh, I was just saying to God that I have come up this high, please don’t take me any higher just yet.’ We both smiled at the thought.

Half an hour after take-off, the drinks trolley came. I asked for a glass of white. Knowing that he was teetotaller, I asked Kaka if he would like anything soft. ‘No, Beta, I am okay. Sab theek hai.’ ‘Nothing? What about soft drinks: tomato or orange juice, water?’ ‘At my age, you have to be careful,’ Kaka said to me some minutes after the trolley had gone. ‘I have to go to the toilet after I have a drink. Can’t contain it for too long.’ ‘Bahut jor pisaap lage’ — but there is a toilet on the plane, Kaka, I reassured him, gently touching his forearm. ‘Actually there are several, both at the front and back of the plane.’ That caught Kaka by complete surprise. A toilet on the plane? ‘You can do the other business there, too, if you want,’ I continued. But Kaka was unwilling to take the risk. Later I realised a possible reason for his hesitation: if he did the other business, he couldn’t wash himself with water — toilet paper he had never used.

When lunch was served, Kaka refused once again. He was a strict vegetarian, a sadhu to boot. ‘You can have some bread and fruit, Kaka,’ I said. He still refused. ‘You don’t know what the Chinese put in the bread,’ he said. In Labasa, all the bread was made by Chinese and a rumour was started, probably by an Indo-Fijian rival, that they used lard in the dough. I did not know but it did not matter to me. In the end, Kaka settled for an ‘apul’ and a small bunch of grapes. ‘I am sorry, Kaka, but I have ordered chicken,’ I said apologetically. ‘Koi bat nahin,’ he said — don’t worry. Everyone in his family ate meat, including his wife. He was its only vegetarian.

My curiosity was aroused. How had Kaka become a vegetarian and a teetotaller? Most people in the village were not. I noticed that the back of his right hand was deformed, his skin burnt and his fingers crooked. ‘Kaka,’ I said, ‘if you don’t mind my asking, how did that happen?’ ‘It is a long story, Beta,’ he said. ‘But we have three hours to kill,’ I replied. This is what Kaka told me. Soon after he got married, he had a large itchy sore on the back of his right palm. Someone had obviously ‘done’ something. Magic and witchcraft, jadu tona, were an integral part of village life, I remembered. One possibility, he said, was his neighbour, Ram Sundar, who might have spread the rumour that Kaka had leprosy, the most dreaded social disease one could imagine, a disease with a bad omen. If Kaka went to Makogai Hospital (for lepers, in the remote Lomaiviti group), the whole family would be ostracised, no one would think of marrying into it, no invitations to marriages and festive occasions. Social pressure would force the family to move to some other place to start afresh, as far away from established settlement as possible. If Kaka had leprosy, he would have to move from the village and Ram Sundar would then finally realise his dream of grabbing Kaka’s adjacent 10-acre farm. Such cunning, such heartlessness, and here was the outside world thinking that warm neighbourly relations characterised village life.

The extended family — because its reputation would be singed too by this tragedy — decided that something had to be done soon about Kaka’s condition. Rumour was spreading fast. Instead of going to a doctor — no one in the village did or really believed in the efficacy of western medicine — his girmitiya [indentured] father sent him to an ojha, a sorcerer, in Wainikoro some thirty or so miles away to the north. The ojha, Ramka, was famous — or dreaded — throughout Vanua Levu. He had once saved the life of a man, Ram Bharos, who had gone wild, squealing like a mouse sometimes and roaring like a lion at others, clenching his teeth and hissing through closed lips, because he had faltered trying to master magic rituals which would enable him to destroy people and cattle and property, even control the elements. To acquire that power, Ram Bharos was told — by whom it was not known — that he would have to eat a human heart sharp at midnight. Nothing was going to deter Ram Bharos from realising his ambition. He killed his own aged father. At night, he went to the graveyard, opened his father’s chest with a knife and put the heart on a banana leaf. After re-burying the body, he walked to a nearby river, with the heart in his hands, and waded chest-deep into the river. Then something frightening happened. He saw a man shrouded in white walking towards him. Suddenly there was a blinding flash of light. Ram Bharos stumbled, forgot the names of deities he was supposed to invoke. He went mad. Ramka cured him partly, restoring a semblance of normalcy to Ram Bharos’ damaged personality. This sounds like an improbable story, but I believed Kaka. Labasa, dubbed the Friendly North, has its dark side as its residents know only too well.

It was to this famous ojha that they had taken Arjun Kaka. In a dimly lit room, Ramka did his magic. He rubbed Kaka’s damaged palm with fat and turned it over the fire for a very long time, chanting words in a language that was incomprehensible to him. By the time he had finished, the skin had been charred. A few days later, the bones had twisted. But Kaka was ‘cured’, he did not have leprosy, the family’s honour was saved, and the farm remained intact. Ramka asked Kaka never to touch meat and not have pork cooked at his home. That was how Kaka had become a vegetarian.

Magic, witchcraft, sorcery, belief in the supernatural, the fear of ghosts and devils, blind faith in healers and magic men: it all recalled for me a world which the girmitiya had brought with them and of which we all were a part, but which now belonged to an era long forgotten, for the present generation nothing more than stories of a twisted imagination. And this man, from that world, was going to Australia! ‘I have forgotten the details, Beta,’ Arjun Kaka apologised. ‘You are the first person to ask me.’ I am glad I did. After Kaka had spoken, I recalled the pin-drop silence of unlit nights in the thatched bure — belo — where we slept, the eerie scurrying of nocturnal animals on crackling dry leaves around the house, the scrotum-shrivelling stories of swaying lights in the neighbouring hills, soft knocks on doors at odd hours, the mysterious aroma at night of scents usually sprinkled on corpses, streaking stars prophesising death somewhere, wailing noises across the paddy fields and shimmering figures in the nearby mangrove swamps. We dreaded nights.

At Sydney airport, Krishna met us. I gave him my phone number and promised to keep in touch. Kaka had a three-month visa and I told him that I would visit him in Sydney. After we embraced, I headed for Canberra, determined that I would do everything I could to give Kaka a memorable journey to Mr Tom’s country. About a month later, Krishna phoned me. Kaka wanted to talk to me. ‘Beta, I am going back soon. I would like to see you before I return.’ ‘But you have a full three-month visa.’ ‘Something inside tells me that I must return as soon as possible.’ A premonition of some sort? His world of magic and sorcery came to mind, and I realised there was no point arguing or trying to persuade him to change his mind. I left for Sydney the following day.

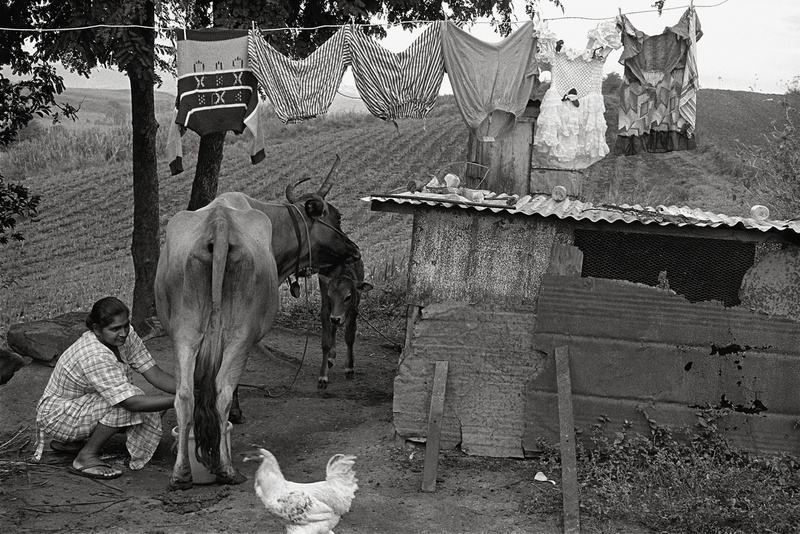

Krishna and his wife had gone to work and the children were at school when I reached the house. It was immediately clear to me that Kaka was a lost man, uncomfortable and anxious. I reminded him of his promise to tell me the full story about his Australian experience. ‘Poora jad pulai’ — everything. What he missed most, Kaka said, was his daily routine. In Tabia, he would be up at crack of dawn, feed the cattle and have early breakfast before heading off to the fields. Even at his age. In the evening, after an early shower at the well, he would light the wick lamp — dhibri — and do his puja. He missed his devotional songs on the radio, the death notices in the evening. He would not be able to forgive himself if someone dear to him died while he was away. Kaka often wondered how Lali, his beloved cow, was. He treated her tenderly, almost like a human, a member of the family. For him, not looking after animals, especially a cow [gau-mata, mother], was a crime.

In Fiji, Kaka was connected, was part of a living community. He had a place in the wider scheme of things. But not here. ‘I sit here in the lounge most of the day like a deaf and blind man. There is television and radio, but they are of no use to me.’ What about a walk in the park, a stroll in the nearby supermarket? I asked. Kaka recalled a particularly hair-raising experience. One day Krishna had left him in the mall of a large supermarket and had gone to get his car repaired. At first Kaka was calm, but as time passed, surrounded by so many white people, he panicked. What if something happened to Krishna? He did not have the home address or the telephone number with him. How would he find his way home? He tried to talk to a young Indian man — who was probably from Fiji — but the man kept walking, muttering to himself. ‘He probably thought I was a beggar or something.’ From that day on, Kaka preferred to remain at home. For a man fond of the outdoors, active in the fields, this must have been painful. ‘It is torture, Beta. Sitting, eating, pissing, farting. That’s all I do all day, everyday.’ I felt his distress.

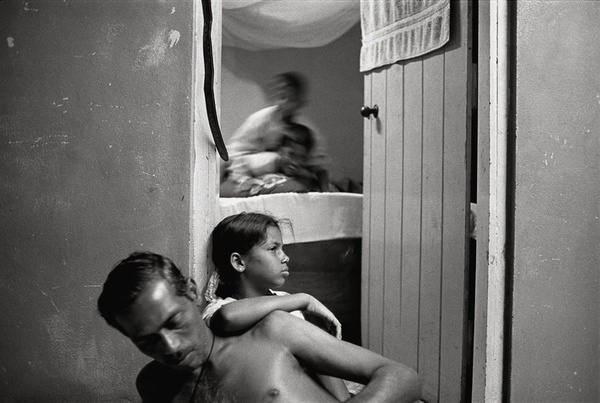

Did Krishna and his wife treat him well, I asked. It was an intrusive question, I know, but I wanted to be helpful. ‘Oh, they both are very nice. Patoh makes vegetarian dishes and leaves them in the fridge for me. I have a room to myself. My clothes are washed. On the weekends, they take me out for drives.’ But there was something missing, I felt. ‘Beta, it is not their fault but I don’t see much of them. Babu [Krishna] goes to work in the morning and Patoh does the evening shift. By the time she returns, it is time for bed.’ The ‘ant-like life’, as Kaka aptly put it, was not his cup of tea. ‘Getting established in this society is not easy, Kaka,’ I said, ‘but things improve with time.’ ‘That’s true, but by then, half your life is over. These people would have been millionaires in Fiji if they worked as hard as they do here.’ ‘They do it for the future of their children, Kaka.’ He nodded. ‘I know, I know.’

Kaka felt acutely conscious of himself whenever he did anything, constantly on the guard. Back home, he would clear his throat loudly and cough out the phlegm on the lawn. Everyone did it. Here his grandchildren giggled and covered their mouths with their hands in embarrassment. In Tabia, Kaka always wore shorts at home. Here, on several occasions, he felt undressed, half naked, when Krishna’s friends came around. ‘I could see that both Babu and Patoh were sometimes uncomfortable.’ Sometimes, the people he met at puja and other ceremonies, especially people from Viti Levu, laughed in jest at his rustic Labasa Hindi. ‘They find us and our language backward. “Tum log ke julum bhasa, Kaka” they would say to me mockingly — Uncle, you folk [from Labasa] have a wonderful language: “awa-gawa [come and gone, when they say ayagaya], dabe [flood, baadh], bakeda [crab, kekda].” They find it funny, but after a while I find the mocking hurtful. So I don’t say much — ka boli — not that I have much to say to these people anyway.’ In Tabia, Kaka had his own kakkus [outhouse] where he could wash himself properly with water after the toilet, but here he would sometimes spill water on the toilet floor or accidentally leak on it, causing mustiness and a foul smell. He would then feel guilty and embarrassed. Kaka found the accumulation of small things like this making him self-conscious, ill-at-ease in the house. No one ever said anything, but he felt that he was a bit of a nuisance for everybody, especially when Krishna’s friends came around.

Kaka was desperate for news from home, any news. There was nothing about Fiji, let alone Labasa, on television and only brief snippets on one or two radio stations, which he often missed because he could not find the right station. His Fiji radio had only one. ‘At home, I knew what was happening in Fiji and the world, but here I sit like a frog in a well. It is as if we do not exist.’ I understood his puzzlement. Fiji — Labasa — was all he knew. His centre of the universe was of no interest and of no consequence to the rest of the world. ‘That is the way of the world, Kaka,’ I tried to assure him. ‘We are noticed only when we make a mess of things, or when there is a natural disaster or when some Australian tourist gets raped or robbed.’ Some of the people he had met, especially the older ones, hankered for news from Fiji, but the younger ones were too preoccupied with life and work

Television both entertained and embarrassed Kaka. He couldn’t watch the soaps with the entire family in the room. The scantily clad women, the open display of skin, the kissing, the suggestive bedroom scenes, the crude advertising (for lingerie, skin lotions), had him averting his eyes or uttering muffled coughs. Sometimes, unable to bear the embarrassment, he would just retire to his room on the pretence that he was tired, and then spend much of the night sleepless, wondering about everything. He liked two shows, though, and enjoyed them like a child. One was David Attenborough’s nature programmes. He did not understand the language but the antics of the animals and creatures of the sea did not need words to understand. These programmes brought a whole world alive for him. He remembered the animals his girmitiya father used to talk about: sher [lion], bhaloo [bear], hathi [elephant], bandar [monkey]. He had seen pictures of them in books, but to see live animals on the screen was magical. And he liked cartoons, especially the Bugs Bunny shows. They made no sense to him at all — nor to me — but that was their charm, characters skittering across the screen speaking rapid-fire — ‘gitbit gitbit’. He would laugh out loud when no one was watching.

These were the only programmes Kaka could watch with his small grandchildren. Otherwise there was no communication between them. The children were nice — ‘sundar’ is how Kaka described them. They made tea for him and offered him biscuits and cookies, but they had no Hindi at all and Kaka knew no English. He would caress their heads gently and hug them and they would occasionally take him for walks in the park nearby, but no words were exchanged. ‘Dil roye, Beta,’ Kaka said to me — the heart cries — ‘that I cannot talk to my own flesh and blood in the only language I know. I hope they will remember me and remember our history.’ Krishna was making an effort to introduce his children to Indian religion and culture through the weekend classes held at the local mandir, but it was probably a lost cause. History was not taught in many public schools, certainly not Pacific or Fijian history and I wondered how the new generation growing up in Australia, exposed to all the challenges posed by global travel and technology, would learn about their past. I did not have the heart to tell Kaka, but I know that his world would go with him, just as mine will, too. Our past will be a foreign country to children growing up in Australia.

Once or twice, I took Kaka out for a ride through the heart of Sydney, pointing out the monuments — Hyde Park, Circular Quay, the Museum and the Mitchell Library — but Kaka had no understanding and no use for the icons of Australian culture. For him, the city was nothing more than concrete and glass chaos, one damn tall building after another. I took him for a ride in the country, playing devotional Hindi music in the car (which he enjoyed immensely). Kaka had imagined Australia to be clogged with buildings and people, but the long, unending distances between towns both fascinated and terrified him. In Labasa an hour’s journey was considered long; the idea of driving for a couple of days to get from one place to another was alien to him. And the geography too fascinated Kaka: the dry barren countryside wheat-brown in December, the bleached bones of dead animals by the roadside, the rusting hulks of discarded machinery and farms stretching for thousands of hectares. ‘How can one family manage all this by themselves,’ he wondered. ‘How can you grow anything in this type of soil?’ And he wondered how, living so far apart on their farms, the people kept the community intact. I said little: he was wondering aloud, talking to himself. On our return journey, Kaka said sadly that he wished ‘my Kaki’, his wife, could have seen all this with him. I wished that too. I could sense that he was missing her. Kaka remained silent for a long time.

I was still unsatisfied that Kaka was happy with all that Krishna and I between us had been able to show him. Then it came to me that Kaka might like to visit the Taronga Zoo. It was an inspired thought. Kaka was like a child in a garden of delights. The animals he had seen on the television screen he saw live with his own eyes: giraffe, rhino, tiger, leopard, lion, cobra, and elephant. I was so glad that he was enjoying himself, pointing out animals to me, saying, ‘look, look’, with all the excitement of an innocent child. As we approached the monkey section of the zoo, Kaka stopped, joined his palms in prayer and said, ‘Jai Hanuman Ji Ki’ — Hail to Lord Hanuman, the monkey god, Lord Rama’s brave and loyal general, who had single-handedly rescued Sita from Ravana’s clutches. He was excited to see a cobra. ‘Nag Baba,’ he said reverentially — the snake god. When I looked at him, Kaka smiled but I couldn’t tell whether his display of quiet reverence for the monkeys and cobras was sincere or was it for my entertainment! I knew that the old man certainly had an impish sense of humour.

As we were having a cup of tea at the end of the zoo visit, sweetening it with white sugar, Kaka wondered where that was manufactured. The next day, I took Kaka to the CSR refinery. He was thrilled. As already mentioned, we considered white sugar ‘pure’ enough to offer it to the gods in our puja and havan. A supervisor gave us a good informative tour when he found out that Kaka was from Fiji. Kaka was impressed with how clean the place was and how new the machinery was, nothing remotely like the filthy, stench-producing sugar mills in Fiji. We also visited an IXL jam factory on the way. Jam and bread were a luxury for many poor families in rural areas of Labasa, to be enjoyed on special occasions, such as birthdays. The standard food in most homes was curry, rice and roti, with all the vegetables coming.

The visit to the sugar refining factory re-kindled Kaka’s interest in the CSR. He wondered whether any of the kulambar were still alive. ‘We could find out,’ I offered. It would mean a lot of research, but I wanted to do it for this man who meant so much to me. I rang the CSR head office in Sydney. There was nothing on the overseers. Evidently, once they finished with the Company, they disappeared off the record books, a bit like the girmitiya about whom everything was documented when they were under indenture, and nothing, or very little, when they became free. Was there ever an association or club of former Fiji overseers, I wondered. The lady did not know but promised to find out. She rang an hour or two later to say that I could try Mr Syd Snowsill. He was the leader of the Fiji pack in Sydney. The name seemed vaguely familiar; he was, from memory, the spearhead of the Seaqaqa Cane Expansion project in the early 1970s. A gruff voice greeted me when I rang him. When I explained the purpose of my enquiry, he became relaxed. ‘Bahut Accha’ — very good. ‘Who are you after? Anyone in particular?’ I volunteered three names: Mr Tom, Mr Oxley and Mr Johnson. ‘I see,’ Mr Snowsill said chuckling and with some affection. ‘All the Labasa badmaash gang, eh’ — the Labasa hooligans. He did not know the whereabouts of Mr Oxley and Mr Johnson, but Mr Tom — Leslie Duncan Thompson — was living in retirement in Ballina. ‘His name will be in the local telephone book,’ Mr Snowsill said as he wished me good luck. ‘Shukriya ji. Namaste or should I say Khuda Hafiz!’ ‘Both are fine.’

If you do not know it, Ballina (Bullenah in the local Aboriginal language) is one of the loveliest places in Australia. A rural sugar cane growing community of fewer than twenty thousand in sub-tropical northern New South Wales, by the enchanting bottle-green Richmond River and surrounded by a sea of rippling cane fields for as far as the eye can see, tidal lagoons and surf beaches nearby. It was the kind of place I knew that Kaka would like: a rural cane country since the 1860s, the people friendly and genuine, in the way country folk generally are. And he did, as we drove on the Princess Highway through small, picturesque seaside towns, beaches, thickly-wooded rolling hills along the roadside, across a gently gathering

Mr Tom was certainly in the phone book when I checked the next morning. His address was a retirement home on the outskirts of the town, on a small hill overlooking the river. I didn’t ring but drove to the place to give Mr Tom a surprise. My mental picture of him remained of a tall thin man, barking orders. Kaka was smiling in anticipation, perspiring slightly. We waited in the wicker chairs in the veranda as the lady at the front desk went to get him from the dining table across the room. As he walked towards us, I knew it was Mr Tom: tall, erect, with a bigger waist now, face creased and hair gone, but not the sense of purposefulness. ‘Yeash,’ he drawled. When I explained why we had come and told him Kaka’s name, he beamed and hugged him, two old codgers meeting after decades, slapping each other gently on the back. ‘Salaam, sahib,’ Kaka muttered. ‘Salaam, salaam,’ Mr Tom replied excitedly. ‘Chai lao. Jaldi, jaldi’ — bring some tea, quick-fast, he said to no one in particular. Perhaps he wanted us to know that he still had Hindustani after all these years.

‘Tum kaise baitho,’ Mr Tom asked Kaka — how are you? Before Kaka could reply, Mr Tom said, ‘Hum to buddha hai ab’ — I am an old man now. I translated for Kaka. After a while, the names came to Mr Tom: Lalta, Nanka, Sundar (he pronounced it Soonda). He especially asked after Udho, the de facto head man of the village, who was one of the few from Labasa to volunteer for the Labour Corps during World War Two. He had died some years back. ‘Too bad,’ Mr Tom said, ‘he was a good man.’ He asked after Kaka’s family, about the school. ‘I haven’t been to Labasa since leaving, but hear it is a modern place now, not bush place like it used to be. They tell me the roads have been tarsealed and people have piped water. No longer a pukka jungali place, eh. You people

‘Seaqaqa kaise baitho, Arjun?’ — how is Seaqaqa? Mr Tom asked Kaka. That was the project on which he had worked with Mr Snowsill. It had been launched with great hope of getting Fijians into the sugar industry. Half the leases were reserved for them. When Kaka told him that many Fijians had left their farms or sub-leased them to Indo-Fijian tenants, Mr Tom seemed genuinely sad to learn that all the effort that he and other overseers had put in had gone to pot. ‘It was done all too suddenly. They wanted to make political mileage out of it. Win elections. All that tamasha [sideshow]. That’s no way to run this business. We needed to have proper training for them, proper husbandry practices in place. You can’t just pluck them out of the bush and make them successful farmers overnight. Ridiculous.’ ‘Farming is a profession, son,’ Mr Tom said to me, ‘just like any other. It is not everyone’s cup of tea.’ Mr Tom said that the CSR should have remained in Fiji for another five to ten years to effect a good transition, train staff properly, and most importantly to get politicians to see the problems of the industry from a business angle. ‘But no, everything had to be done in a rush. You got your independence and you didn’t want white men around telling you what to do anymore. Fair enough, I suppose, but look at what a mess you have made of the industry.’

Then Mr Tom asked about the current situation. He had read that the industry was in dire straits. ‘I am afraid it is true, Mr Tom,’ I said. Most leases in Daku, Naleba, Wainikoro, Laga Laga — places Mr Tom knew so well — had not been renewed, and the former farms were slowly reverting to bush. Mr Tom shook his head. ‘Sad. So much promise, shot through so early.’ He asked about the farmers. Those evicted were moving out, many to Viti Levu, starting afresh as market gardeners, vegetable growers, general labourers and domestic hands. ‘Girmit again, eh? Unnecessary tragedy. Why? What for? We have all gone mad.’

I asked Mr Tom about something that had been on my mind for many years. ‘Why didn’t the CSR sell its freehold land to the growers when it decided to leave Fiji? It would have been the right thing to do, the humane thing to do.’ Mr Tom acknowledged my question with that characteristic drawl of his, ‘Yeash.’ And then bluntly, ‘We couldn’t give a rat’s arse about who bought the land. All we wanted was nagad paisa [cash]. Fijian leaders understood very well that land was power and didn’t want the CSR to sell its freehold land to Indians. Over 200,000 bloody acres or so. Indian leaders in the Alliance went along, trying to please their masters, hoping for some concessions elsewhere. The Fijians and the Europeans — Mara, Penaia, Falvey, Kermode, that crowd — had them by the balls. We in the Company watched all this in utter incomprehension and disbelief, but it wasn’t our show. We were so pissed off with the Denning Award.’ He was referring to the award by Lord Denning, Britain’s Master of the Roll, which favoured the growers against the millers and which led eventually to CSR’s departure from Fiji in 1973. ‘And then there was the Gujarati factor, did you know?’ I didn’t. ‘Some of your leaders feared that if Indian tenants got freehold land, Gujarati merchants would get their hands on it by hook or by crook. To some, the Gujarati were a bigger menace than Fijians and Europeans. Such bloody short sightedness. Son, some of your suffering is self-inflicted. Harsh thing to say, but it’s true.’

After a spell of silence, Kaka wanted to know about Mr Tom’s life after Tua Tua. From Tua Tua he had gone to Lomowai and done the rounds of several Sigatoka sectors (Kavanagasau, Olosara, Cuvu) before moving to Lautoka mill as a supervisor. Taking early retirement, he returned to Australia, and after some years of working in Ballina’s sugar industry he ‘went fishing’, as he put it — travelling, taking up golf and lawn bowling. I vividly recalled lawn bowling as the game white people, in white uniforms and white shoes, played at Batanikama. Wife and children? Kaka wanted to know. The wife had died a few years back, which is when he moved to this place. The children were living in Queensland. ‘There is nothing for them here.’ Kaka wondered, smiling, if Mr Tom still had that fearsome taste for hot chillies. ‘Nahin sako, Arjun’ — can’t do it anymore. ‘Pet khalas’ — the stomach’s gone. ‘And what do you do, young man?’ Mr Tom asked me. When I told him that I was an academic in Canberra, he smiled. ‘Shabaash, Beta, kya baat’ — well done, son. ‘Boy from Labasa, eh! Who would have thought! From the cane fields of Fiji to the capital of Australia. You joined the bloody know-all academics! Good onya, son.’

We had been talking like this for an hour or so when the topic of the coups in Fiji came up. Mr Tom had been outraged by what had taken place. There was some support in sections of Australia for the coups, which saw them essentially as the desperate struggle of the indigenous community against the attempted dominance of an immigrant one. But Mr Tom was different. ‘I wrote letters to the local papers, gave a few talks and interviews on the radio. No bloody use. Look, I said, you don’t know the Indian people. I do. I have worked with them. I understand them. They made Fiji what it is today. They have been the backbone of the sugar industry. You take them out and the whole place will fall apart. Just like that. What wrong have they done? How have they wronged the Fijian people? Their only vices are thrift and industry.’ He went on like this for some time. I was not used to hearing this kind of assessment from people in Australia. Mr. Tom was refreshingly adamant, defiant.

‘Yours must have been a voice in the wilderness, Mr Tom,’ I said. ‘Bloody oath, yes. You talk about immigrant people ripping natives apart. Bloody well look at Australia! Look what we have done to the Aborigines. Snatched their land, made them destitute, pushed them into the bush, robbed them of their rights. Bloody genocide, if you ask me. What have the Indians done to Fiji? They worked hard on the plantations so that the Fijians could survive. What’s bad about that? If I had my way, I would bring the whole bang lot here. We need hardworking people like you in this country.’ Mr Tom had spoken from the heart. ‘Let me not go on, because all this hypocrisy lights me up.’ ‘Mr Howard would not approve,’ I said. ‘What would these city slickers know,’ Mr Tom said dismissively. ‘They don’t know their arse from the hole in the ground, if you ask me.’ I had heard many a colourful Australian slang — blunt as a pig’s arse, knockers, spitting the dummy — but this one was new. I smiled, and appreciated Mr Tom’s unvarnished directness.

It was time to go. Once again, Kaka and Mr Tom hugged. ‘Well, Arjun, nahi jaano phir milo ki nahin milo’ — don’t know if we will ever meet again. ‘Look after yourself and say salaam to the old timers.’ With that we headed back to Sydney. I told Kaka all that Mr Tom had said. ‘Remember, Beta, what I told you: many kulambar were tough but fair. We were not completely innocent either: chori, chandali, chaplusi’ — thievery, stupidity, wanton behaviour. I was impressed, even touched, by Mr Tom’s directness and his principled, uncompromising stand on the Fiji coups. I had not expected this sort of humanity in a former kulambar, whose general reputation in Fiji is still rotten. Talking to Mr Tom and driving through the cane country brought back many memories of growing up in Tabia more than a half century ago — of swollen brown rivers in the rainy season, the smell of pungent cane fires reddening the ground, cane-carting trains snaking through the countryside, little thatched huts and corrugated iron houses scattered around the dispersed settlements, smoke from cooking fires rising gently in the distance, little school children in neat uniforms walking Indian-file to school. ‘You are a godsend,’ Kaka had said to me when I had offered to bring him to Australia with me. In truth, Kaka was a godsend for me. With him, I had re-visited a world of which I was once a

I dropped Kaka at Krishna’s place and returned to Canberra. I was going to Suva for a conference in a couple of months’ time and promised to see him then. Tears were rolling down his stubbled cheek as he hugged me. ‘Pata nahin, Beta, ab kab miliho’ — don’t know, son, when we will meet again. I didn’t know it then, but it was the final goodbye. A month after Kaka returned, Krishna rang to say that he had died — of what precisely no one knew. I was speechless for days. The last link to my past was now gone, the last one in the village who had grown up in the shadow of indenture, lived through the Depression, the strikes in the sugar industry, the Second World War. I felt cheated. I still feel his loss. With Kaka gone, one more familiar Tabia signpost had disappeared from my life. After a brief moment of promise, the place once again became a labyrinth of haunting memories.

When I returned to Fiji, I knew that I had to go to Labasa. Perhaps it is the ancient urge to say the final goodbye in person. I wanted to know the exact circumstances of Kaka’s death. Only then could I finally come to terms with my grief. Kaka had been happy to return home, back in his own house, back to his daily routine, people told me. Then one day, all of a sudden, Lali, the cow, died. Kaka was distraught; she was like family to him. Lali was his wife’s gift to him when their first grandchild was born. He used to talk to her everyday, caress her forehead, religiously feed her para grass every morning and afternoon, wash her once a week. People said that Kaka talked to Lali as if he was talking to his wife, telling her his doubts and fears, using her as a soundingboard for his ideas and plans. Now a loved link to that past was gone. He was heart broken. In fact, he had died from a massive heart attack. The last words Kaka spoke before he collapsed, one of his grandchildren remembered, was ‘Dhanraji, taharo, hum aait haye’ — Dhanraji, wait for me. I am coming.

BRIJ VILASH LAL / 02.2007