texts

2022-11-09

Two countries called Fiji, 9 September 2000

And none of it pointed to democracy.

In a three week journey to Fiji during the 2000 George Speight coup d’état, Bruce Connew went to the core of Fiji custom and tradition, and found hapless family squabbles. Later, amongst the Indian cane cutters in the west of Viti Levu, he found toilers with a sense of political realism. Back in Suva, a Fijian told him how it worked. And none of it pointed to democracy.

For the NZ Listener magazine, 9 September 2000.

My two elder daughters both have Fijian partners. I hadn’t thought this so extraordinary – until the coup. Then I began to think, how do I deal with this? One is an Indo-Fijian who arrived in New Zealand with his parents after the last coup, and the other an indigenous Fijian here on a university scholarship. They are almost as dear to me as my daughters. They get on well, and in fact once lived not far from each other in a middle class suburb of Suva. But when we sat around the table talking after Speight had stormed parliament, it brought to mind other conversations we’d had. I can remember thinking during some of those conversations that each of them was describing a different Fiji, a different country almost.

A week after Speight sets free the last of the hostages, I will watch my second daughter’s Fijian partner caress her temple as a contraction takes hold. Before morning, they will have had a son, my first grandchild, a boy, the first boy of the eldest son, a half caste, ‘the boss’, says his Fijian grandfather. The next day, the Indian partner of my eldest daughter will sit on the edge of the hospital bed, and hold the swaddled baby close to him as he reads the front page of a newspaper.

I’m keen to look around these countries, I tell them. My plan is to be back in plenty of time for the birth. Two days in Fiji, and the parents of my second daughter’s partner invite me to a funeral. A big funeral. A paramount chief. Bau Island, powerful well beyond its few indigenous hectares. They loan me a school history book, so I’ll better understand the weighty significance of Bau. It is day 39 of the coup. They tell me to photograph the ironies at the funeral, and I wonder how do you photograph ironies, and which are the ironies?

The coffin is all over the place, anything but level, as the pall bearers negotiate the mud of the steep and slippery slope to the tomb. I can see their shoulders reddening beneath the weight. Hundreds of mourners follow. What must be going through the mind of the dead chief’s brother, Ratu Epeli Nailatikau, in his white shirt, tie and sulu, mud slushing over his leather boat shoes? The rebels have just released his wife. She is a daughter of Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara, the dislodged president, and is here today. In a few days, we will learn that Epeli is to be deputy prime minister in the military’s interim government.

The first king of Fiji was from here: Ratu Seru Cakobau. He ceded Fiji to Queen Victoria in 1874. I smile wondering whether Queen Elizabeth knew, on a visit to Bau in 1982, as she passed the spirit temple, hand bag and white gloves, that beneath its four corners are the skeletons of four strong men, not all that long ago, ritually buried alive with each corner post?

There has been been no king of Fiji for the past 10 years, not since the last one died. The contenders among the Bau Island kingly families cannot agree on which of them it should be. Ratu Epeli is one of five contenders. He says later in a newspaper story, his very thin upper lip prominent in the photograph, that this procrastination, the power struggle for the title, is behind the current strife. A rudderless Kubuna confederacy. And this is where the ironies begin to come in. There are three confederacies, and right now there is a clash between two of them: Kubuna and Tovata. The king, when there is one, is the traditional head of Kubuna. The head of Tovata is Ratu Mara. Since independence in 1970, it has been Ratu Mara, and therefore Tovata, who has held most sway. Kubuna is reasserting itself.

The mourners at this funeral, I have drummed into me, are the ironies. I flick back to the names given to me the previous evening: tribal enemies, family enemies, political enemies, business enemies, and some of them, all of these at the same time. Bickering bitternesses, dark histories. It’s so convoluted that rather than unravel the detail of power, the plethora of opinions only pulls the knot tighter.

Adi Litia Cakobau is one of the names. Daughter of the last king, with a heritage back to the first. This blood, very distantly, will be that of my grandchild, and the reason I’m permitted on the island today. A coup plotter? Her sister, Adi Samanunu Cakobau, Ambassador to Malaysia, Speight reveals as his choice for prime minister. I want someone to point them out, but no one can find them. When I put their names later to a contact in Suva, he shakes his head. Supporters, yes, but not organisers. He gives me a different name. Iliesa Duvuloco, Nationalist Party leader. A coup plotter? He nods rhythmically. Who knows? On the day of the coup, Duvuloco’s son stole the prime minister’s Korean four-wheel drive, and took off for a joy ride to Nausori, a town on the cusp of Tailevu, the largest province in Kubuna confederacy.

My first night in the country, a woman offers me a tatty photocopy. It is a frightening list of bad deeds, including murder. Ratu Mara, my informant explains. Disinformation? Kubuna? No question. There is no sign of him at the funeral among the Lau Group delegation. Yet, through strategic marriages his blood runs thick in Bau. And that’s another rub. These blood connections between confederacy clans would seem to count for nothing in the face of family rivalries.

Key faces are missing, and it’s becoming awkward to ask for more. But I am encouraged to believe they are here. Perhaps it is my imagination, but there is a smell in the air, on this day of farewell, of unclean affiliations and shifting powers. An unlikely mix, here from all over the country, will whisper not a word of the grubbiness consuming Fiji. They will enter the church, heads bowed, and sing as one: The Sands of Time are Sinking, The Lord is my Shepherd and Now Praise We Great and Famous Men.

There is one village whose men are the grave diggers for the chiefly families of Bau. After they lower the coffin, they sit on top of and around the lid of the tomb, about 20 of them, their hands behind their backs, and pass between them the bitter leaf of the kura, each taking a bite before giving it over to the next, around and around. After the ceremony, I follow their irregular file down to the sea. Fully clothed and with shouts and guffaws, they dive in. A customary ritual cleansing.

As I snap away at their ungodly yahooing in the water, questions trickle to mind. I had listened earlier in the day to two old women disapprove the slipping of tradition. Next to them sat a young boy pumping recklessly at PlayStation. I thought, as I switched from one to the other, is custom as tightly woven into the Fijian psyche as some would have you believe? Or is a new world claiming the minds of the next generation? And will it be this generation who will rattle the tired old power bases seen mourning this afternoon?

Back in Suva, I settle in between the block walls of my motel room to read a couple of pages passed to me about the intricacies of Speight’s dubious mahogany dealings. As I wearily skim the type, it crosses my mind, how intact has remained the independence of the judiciary? Has it come out of this debacle well? After all, it has written decrees for the military, which is less than a good sign. And a military tainted by its early inaction has been there for the world to see. When I put this to a Fijian lawyer the next day, he says that the Chief Justice will be pragmatic, not academic. There’s the answer. I ask how then will the judiciary respond to a court challenge on the setting aside of the 1997 Constitution, keeping in mind that the constitution has yet to be legally abrogated? The reply is succinct. The Chief Justice will appoint the judge. Nothing here to warm a deposed prime minister’s heart.

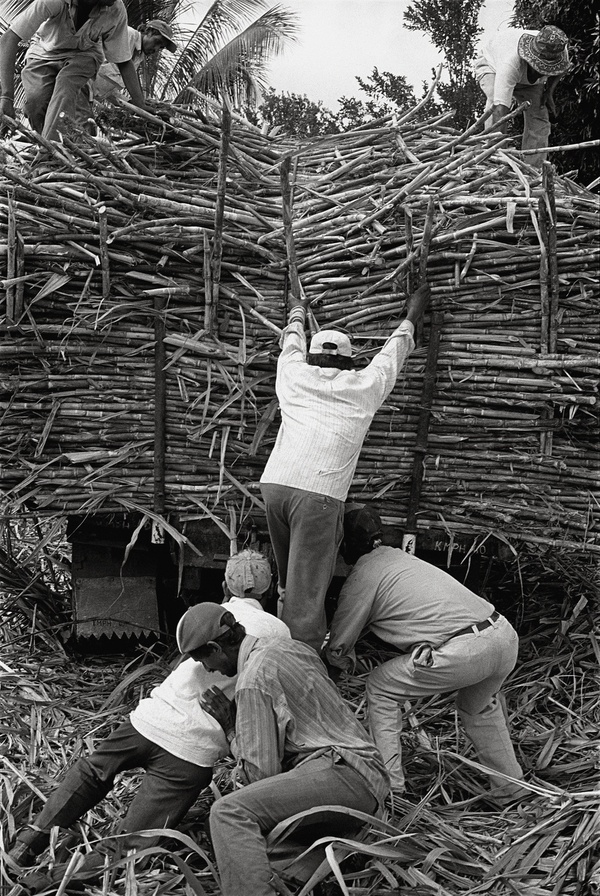

I move to Ba in the west, where Chaudhry was born, and to the cane fields where the Indians first came into this unbalanced equation. They immigrated under a dreadful indentured labour system that impelled many of their young men to suicide. My eldest daughter’s partner, the Indo-Fijian, lived here as a kid. He said they have a very good soccer team.

“I want to talk to someone about the coup,” I say to several earnest young men seated randomly about a front office. After a lengthy silence, one of them points to a chair. I have stumbled across the Ba headquarters of both the Fiji Labour Party and the Federated Farmers’ Union, the union of which Chaudhry was secretary. It looks like a small disused shop. Their names, in red block type, share the front window. From the back emerges a large Indian man who introduces himself as Gaffar Ahmed, assistant Minister of Home Affairs in the Coalition government. “Were you not taken hostage?” I ask. He was, but signed away his position in return for his early release by Speight. In Ba, he has forfeited respect for doing so.

I ask him what Chaudhry did wrong, and he sets forth on a long list of what Chaudhry did right. Staple food prices down, the electricity rate down, the water rate down, mortgage interest rates down, free education up to form 5 (previously form 3), good socially responsible stuff. They maintained investor confidence, he says, and recites a number of hotel projects, jobs for 4000 workers. I try again for what Chaudhry did wrong, but Mr Ahmed has an engagement now with the young men still in his office, all of whom are leaning forward in their short sleeves intent on our conversation.

I set out for the cane fields with a farm advisory officer from the Fiji Sugar Company. An Indian. Forty-two of his extended family now live in Canada, including his eldest daughter who will become a doctor. He and his wife will remain to face the challenge, as he puts it, of this latest reversal, although she smiles coyly at her reluctance. Their remaining three children will study hard, then leave. In a country that sees them as second-class “guests” who must act accordingly, it is hardly a surprise that Indian students display a greater desire for educational success than Fijian. It will be their way out.

A short and middle-aged shop keeper from Ba turns up, as arranged, at my hotel. We drive a little way out of town to visit a long-retired Indian civil servant, someone who was close to Mara, he tells me. We pass cane farms once leased by Punjabis and Gujaratis who, he continues, understood very clearly the tangle of obstacles ahead. They left for the United States, even before the last coup. Indians and Fijians are much closer in the west, anyone will tell you, and the shop keeper tells me now. Not quite blood brothers, but there are not the same resentments as those wafting about in the east of Viti Levu. While there is some truth in this, not far into any conversation, even in the west, each side pops out a stereotypical contempt for the other. He does too. Put simply: Fijians are lazy and Indians want only money. Neither is true, but these dearly held trademarks have come to define the cultural abyss separating the two races.

We drink kava from modest enamel bowls, while several toads clean up the insects on the civil servant’s verandah. He speaks at length about Fijian history, from cannibalism and missionaries to girmits and sugar companies. I listen and take notes, but I’m impatient for him to land at current events. When he does, what he has to say is astonishing. The two races, he says quietly, cannot continue with parallel development. It has not worked, and will not work. Either the two integrate – by this he means inter-marry, become one – or the Indians must leave. The Indians must leave.

On the ride back to my hotel, we pass a Hindu temple nestled amongst the tall sugar cane, and an elegant mosque in the middle of town, symbols that make the integration he speaks of, impossible to presume. The Indians must leave? Was he pulling my leg? His parting statement through the car window was that the Indian population will reduce from its current 43 to 30 per cent. That made more sense.

The roads are diabolical as we negotiate the grass roots of Chaudhry’s support. And it is here, among the deposed prime minister’s staunchest supporters, loyal to the core, that a picture begins to develop. The water man dispenses cool water from a large aluminium teapot for the cane cutters scattered about, resting on the discarded leaves of the cane they have just cut. The sweat runs freely from them. They earn seven dollars a day, and not one wouldn’t vote for Chaudhry again. As we talk more, however, from farm to farm, field to field, man after man admits to apprehension with Chaudhry’s installation as prime minister. When asked why, most grimace: arrogance. The toughest, most intelligent and successful trade unionist in the country. They knew, only too well, that many of Fiji’s dethroned powerful, to which you must attach a few wealthy Indian businessmen, would not cope with a socialist prime minister, an Indian prime minister, and, in particular, this Indian. May 19 came as no surprise.

On the front porch of the Ba Hotel, I ask the Indian manager, “Are the powerful in Fiji so abysmally intolerant, that the brashness of a single Indian can lead to a coup? Or is it something else?” He purses his lips and shrugs.

I climb aboard an inter-city bus and aim for Suva, but the road ahead is anything but clear. An hour and a half into the journey, the bus pulls in at Rakiraki, near the top of Viti Levu, along the Kings Road. The driver turns off the engine, stopping the Bollywood video short of its climax. There is a great deal of excited talk. Another bus pulls up alongside, just in from Suva, and a little melee forms beneath my open window. The short of it is, there’s a rebel roadblock at Korovou, in Tailevu country, Speight’s supporters, about two hours further on. The bus alongside was the last to make it through. They hijacked the earlier one from our end and robbed the passengers, the Indian ticket man says.

We have a choice he gravely explains. Stay in Rakiraki and get a full refund of your fare, or take the bus back, and you will have nothing more to pay. I opt for the second, after dropping thoughts of a taxi to the roadblock to see what is going on. Civil unrest can wait until tomorrow. I bus many hours in the opposite direction, and reach Suva in the dark half an hour before curfew.

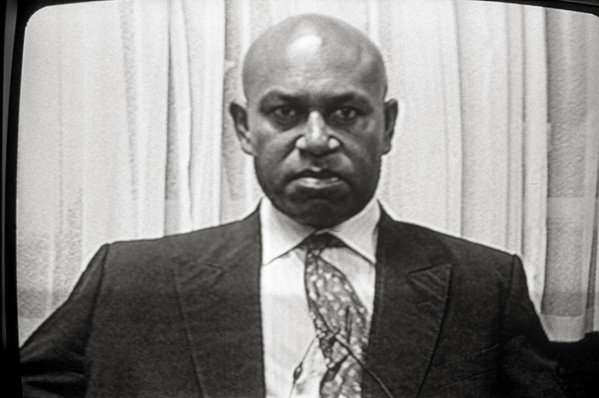

I offer to keep Jone Dakuvula’s name out of the story, but he says it’s okay. Jone was the one who bad-mouthed Speight and his group on television, and ten minutes later a mob ransacked the station. They just missed Jone who had had the presence of mind to leave quickly. On the advice of a friend, he slept away from home that night.

I want to know, how did the SVT react? This was Rabuka’s party, the one sponsored by the Great Council of Chiefs, and supported by the ultra-nationalist Taukei Movement, the big losers at the polls in 1999. Dakuvula was on the inside, you could say. Although he’s now with the Citizens Constitutional Forum (their motto: one nation, diverse peoples), and even once, way back, an organising secretary in Chaudhry’s Fiji Labour Party, for years he was a media adviser in Rabuka’s prime minister’s office. The new leader of the new Opposition brought him in as a close adviser. Dakuvula resigned, disillusioned, three months after he began.

This is what he tells me. Their crushing defeat at the hands of this Indian shocked the many SVT Members of Parliament who had lost their seats. At their angry post-election meeting, they told Rabuka there must be a military coup, but Rabuka refused, swearing by the 1997 Constitution, and resigned. A rabble-rousing speech later by their new leader, Ratu Inoke Kubuabola, demands that the life of the People’s Coalition government be “if blood is to be shed, we must prepare for it”.

“I was quite surprised when I heard this,” says Dakuvula. “They were talking about kidnap, burning, a coup, murder. And they were serious. Given the army or weapons, they would do it.”

The army command declined, so it goes, but a group of its Special Forces stepped forward, and offered the coup plotters the military coercion they needed. The rest of the army held together under Commodore Bainimarama, their commander, when the potential for it to spin out of control could only have been enormous. It restrained its muscle, declaring a peaceful solution paramount. The hostages were the key. But Dakuvula puts another spin on it. The army, he says, split about 70/30 in favour of the commander. With a wrong move, that cut could have turned round completely. The army, he explains, is very professional, well trained, well disciplined, very able. However, in the context of Fijian events, some of that goes out the window, and other communal concerns count for more. The recent shoot-out, and mass arrest of Speight and his supporters, would seem to have called that bluff. But I’m not so sure. Like the judiciary, the army hasn’t come out of this well.

It is early evening, warm but not hot, and we are at a small table on my hotel balcony. Dakuvula balances on the edge of his chair, and talks of a committee formed soon after the election defeat, within the SVT, to destabilise the new government. The Nationalist Party joined these shadowy meetings, and so too did a breakaway group from the Fijian Association Party, grumpy that Chaudhry had neglected to consult them on who should become prime minister. Predictably, they had coveted their party leader, a Fijian. Perhaps foolishly, they did not assemble until the Tuesday following the election, by which time Chaudhry was prime minister. And so the disinformation campaign began, a mean-spirited crusade to put Chaudhry and democracy where they are today.

He was always going to be up against it, Dakuvula explains, if only because he was Indian. But he didn’t help himself. Dakuvula hands me an example to make it clear. His son had regularly screeched, quite rightly, of nepotism in the previous government. Yet one of Chaudhry’s first moves as prime minister was to appoint his son as his private secretary. To top that, says Dakuvula, the son had even more lip than the father. Fijian misgivings soared.

What else? He rejected out of hand, the conditions set by the SVT to join his cabinet, as they had a right to do under a peculiar electoral system that allows the Opposition, the losers, to have seats in cabinet. Immovable. In one breath, he legitimised the cause of the very people who aimed to do him harm. Forget his social and economic policies, they meant nothing to these people.

His Land Use Commission, Dakuvula explains, became another cripplingly misguided political move. Very responsibly, it tackled the pressing land issues hopelessly neglected by previous [Fijian] governments. But instead of paying due respect to two crucial institutions, the Great Council of Chiefs and the Native Lands Trust Board, the Commission by-passed them, choosing instead to deal directly with landowners, an alienation, particularly of the head of the NLTB, Marika Qarikau, that could not have been more complete.

I walk with Dakuvula downstairs to his car. On the way back up, I ponder the dark forces he’s told me about. If the names he’s given me are correct, they are a bunch as mixed as those in 1987. Some of them genuinely believe multiracial democracy (and Chaudhry) to be a threat to the well-being of indigenous Fijians. They’ve been at it a long time. But others have hidden behind the image of selfless fighters for the indigenous cause, when their truth is elsewhere. How could a whole ground swell of Fijians be convinced, by those with other agendas, that Chaudhry’s master plan for Fiji was “a little India”? And why didn’t Chaudhry counter the crass disinformation campaign? Is he a politician or not?

Sick of it all, I slip back into New Zealand to await my grandson’s birth. He comes three weeks early. 6lb 8oz. I stand with his Fijian father and laugh about Speight and his group being hostages of the military on an island once a quarantine for indentured Indians. They have done their dirty work. But what of the powerful behind them? I lunch with Brij Lal, one of three architects of the 1997 Constitution, at the home of the Indo-Fijian parents of my eldest daughter’s partner. We talk of the same things.

From their hill suburb, I look out to Wellington harbour struggling to imagine them ever having lived in the places I’ve just been. Flickering pictures transport me back to the Fiji military’s nightly spokesman on television, and a word he repeats like a mantra: normalcy.

It crashes around in my head because Fiji is where my grandson and my daughter and her partner will have to live, at least some of their lives. A return to normalcy? What he means is an end to the violence. Not a return to democracy.

BRUCE CONNEW / 09.2000

This aged photograph is of two Indian-Fijian men. They are most likely early descendants of indentured Indian immigrants brought to Fiji between 1879 and 1916 to cut sugar cane on unforgiving, five-year contracts; or perhaps one of them is an indentured Indian immigrant, and out of indenture given the likely date of the photograph. No one is quite sure. I came across it loose inside the back cover of a cane cutter’s family photo-album.