Beyond the Pale

“This, the archetypal working class, has seen its emotional influence dwindle as steadily as it’s numbers and along with its political and economic power.”

exhibition & prints

‘Beyond the Pale’ was first exhibited at the Dowse Art Museum, Wellington, New Zealand, August 1988, when James Mack was director. The exhibition toured various venues in Buller and Westland, including the Whataroa School Hall and the Rununga Working Men’s Club, and then showed at Auckland Art Gallery, Auckland, New Zealand, February-April 1990.

The complete series was collected in 1988 by the Dowse Art Museum.

film

‘Kaleidoscope’, a then Television New Zealand arts programme, made a 17-minute documentary, in 1986, directed by Howard Taylor, of my work photographing the last of the native sawmills on the West Coast, New Zealand.

Soon after this, I began ‘Beyond the Pale’ with underground coal miners on the West Coast, a series which, one day, will be a book.

The period was immediately before the ‘corporatisation’ of New Zealand, when the extreme right-wing Labour Government of New Zealand changed everything.

related writings

- Future of Work (briefs)

- ‘Ways of Being’ (briefs)

- ‘Ways of Being’ (reviews)

- Dowse Art Museum (briefs)

- Underground coal miners (briefs)

- ‘Beyond the Pale’, Bruce Connew, 20 August 1988 (texts)

view all 47 works with print/price particulars

“In the city, the miners’ hard labour produces less a feeling of awe than a fascination at the antiquity of their task.”

I wrote the following story for the New Zealand Listener magazine, 20 August 1988, to coincide with the opening of ‘Beyond the Pale’ at the Dowse Art Museum, Wellington, New Zealand.

MY UNCLE JIMMY died in 1984 shortly before he was to retire as Chief Inspector for Coalmines. He first took me down a coalmine up in the clouds at Denniston 24 years ago. I was comfortable underground although I had not yearned to be a coalminer, and still don’t. My grandfather Fred Connew, my uncle’s father, worked underground at Denniston and Stockton in the earlier part of the century and on the locomotives too out of the Stockton mine to the rope road. He was president of the Stockton Miners Union for 30 years. Great Uncle Joe worked the middle break on the Denniston incline.

As a 14 year old boy, my father, Keith (also known as Fred), walked up the incline behind Ngakawau every morning for months before being taken on, to follow the early morning deputy who checked the mine’s safety before the day shift. Sometimes, he had to dig out Mr Rees as he only dared call him when the deputy’s prodding checks of the roof brought an unsafe section down around his ears. Dia Rees taught my father to waltz during several of these early morning inspections.

After not too many months, Dad, who tells a good story, preferred the bowels of a ship to the bowels of the earth, left the mine and joined the navy. He stayed with the navy almost as long as my uncle, his brother, did with State Coal.

Outside of their communities, there is nowadays, scant fellow-feeling for the coalminer. In the city, the miners’ hard labour produces less a feeling of awe than a fascination at the antiquity of their task. If grubbing about beneath ground in a “cosy sort of hell” isn’t seen as an anachronism, certainly hard labour as a livelihood is.

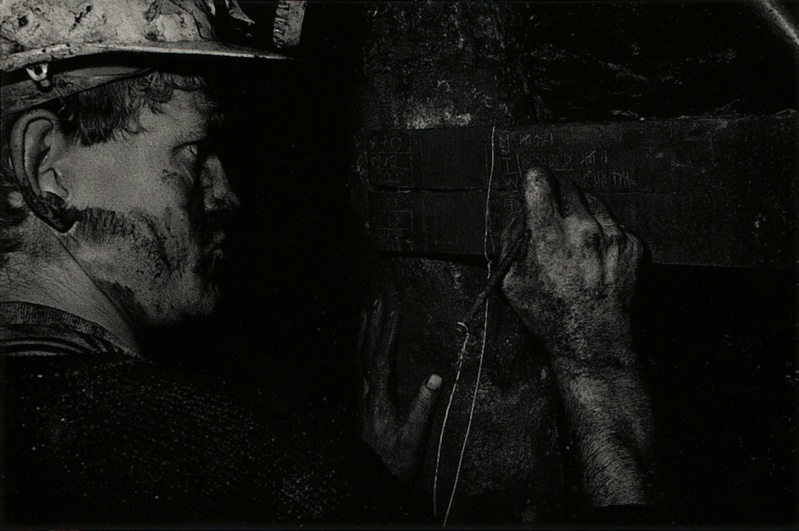

This, the archetypal working class, has seen its emotional influence dwindle as steadily as it’s numbers and along with its political and economic power. The dubious mantle of masculinity for so long fastened to the glory of labour as personified by miners and their sweat has shifted to the money of the city (line from a recent Coalcorp advertisement: When you deal with Coalcorp you are dealing with professional people who wear suits) and the exulted urban athlete.

A prolonged photographic project—this one was 5 months—provides scope to explore beyond the narrow preconceptions of a magazine’s needs and to consider otherwise ill-considered themes. Who would have guessed that in this decade of men’s groups that for the better part of the century miner’s have been washing the coal and sweat from each other’s backs? In rugby and rowing showers (my experience), men, in jest, threaten to touch and, perhaps, even pee on each other; but to stand one behind the other and soap a fellow’s back… well, no! A mine manager, when questioned on this ritual, said, concerned, “You’re not making them out to be a bunch of queers, are you?”

In a recent television sponsorship advertisement for Steinlager beer and the All Blacks rugby team, a miner’s pick fleetingly slams into coal amid powerful, sweaty, rugby bodies (Orwell’s “splendid” bodies!) exploiting, with nostalgia and sentimentality, the intimacy of shared danger and common effort. The final seven photographs in the exhibition turn that not-to-be-discounted mateship stereotype on its head through the imagery of aloneness, and steadily work back towards that intimacy of comradeship.

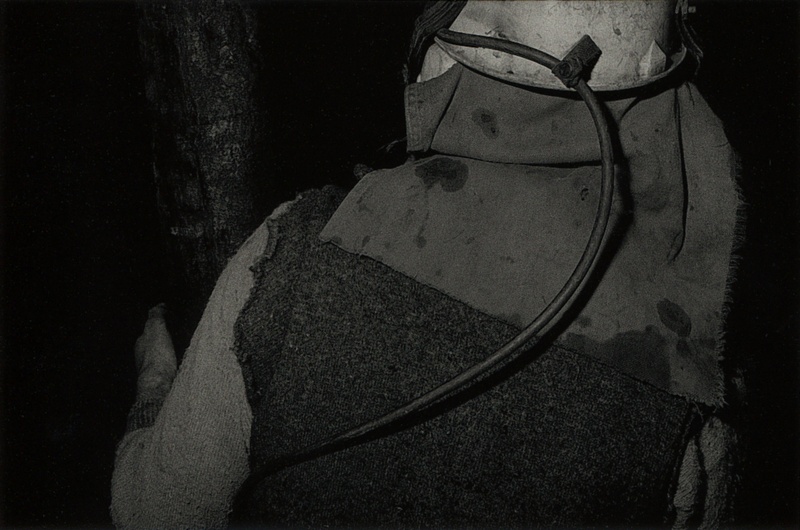

Photography has the facility to be a true account of a certain moment in time while, at once, remaining aloof from the context of the moment. The photograph of Penthouse nakedness pinned eloquently across a grubby beam with the word WINCH chalked at one end is proof in itself that that moment in time did exist. Beyond the existence of that moment, ripe for interpretation, is the ambiguity of photography.

Fundamental to that ambiguity are the visual symbols carefully included (and excluded) by the photographer at the time of exposure and later at the editing and sequencing stage for the gallery walls (or book or magazine): his bias. How the viewer now interprets this photograph and the others and connects one with the other is dependent upon the viewer’s assumptions, social conditioning, morality and even which side of the bed he/she climbed from that morning.

BRUCE CONNEW / 08.1988

view all 47 works with print/price particulars

Beyond the Pale #47 / Firing wire, Strongman Mine, 9 Mile, Westland, New Zealand, 1986

Beyond the Pale #23 / Chris Menzies, Tiller Mine, Dunolie, Westland, New Zealand, 1986

Beyond the Pale #30 / David Featherston, Starline Mine, Reefton, Westland, New Zealand, 1986

Beyond the Pale #32 / Jimmy ‘Grub’ Duggan & Brucie Brown, east heading haulage, Strongman Mine, 9 Mile, 1986, Westland, New Zealand, 1986

Beyond the Pale #27 / Steve Blenkiron, Tiller Mine, Dunolie, Westland, New Zealand, 1986