On the way to an ambush

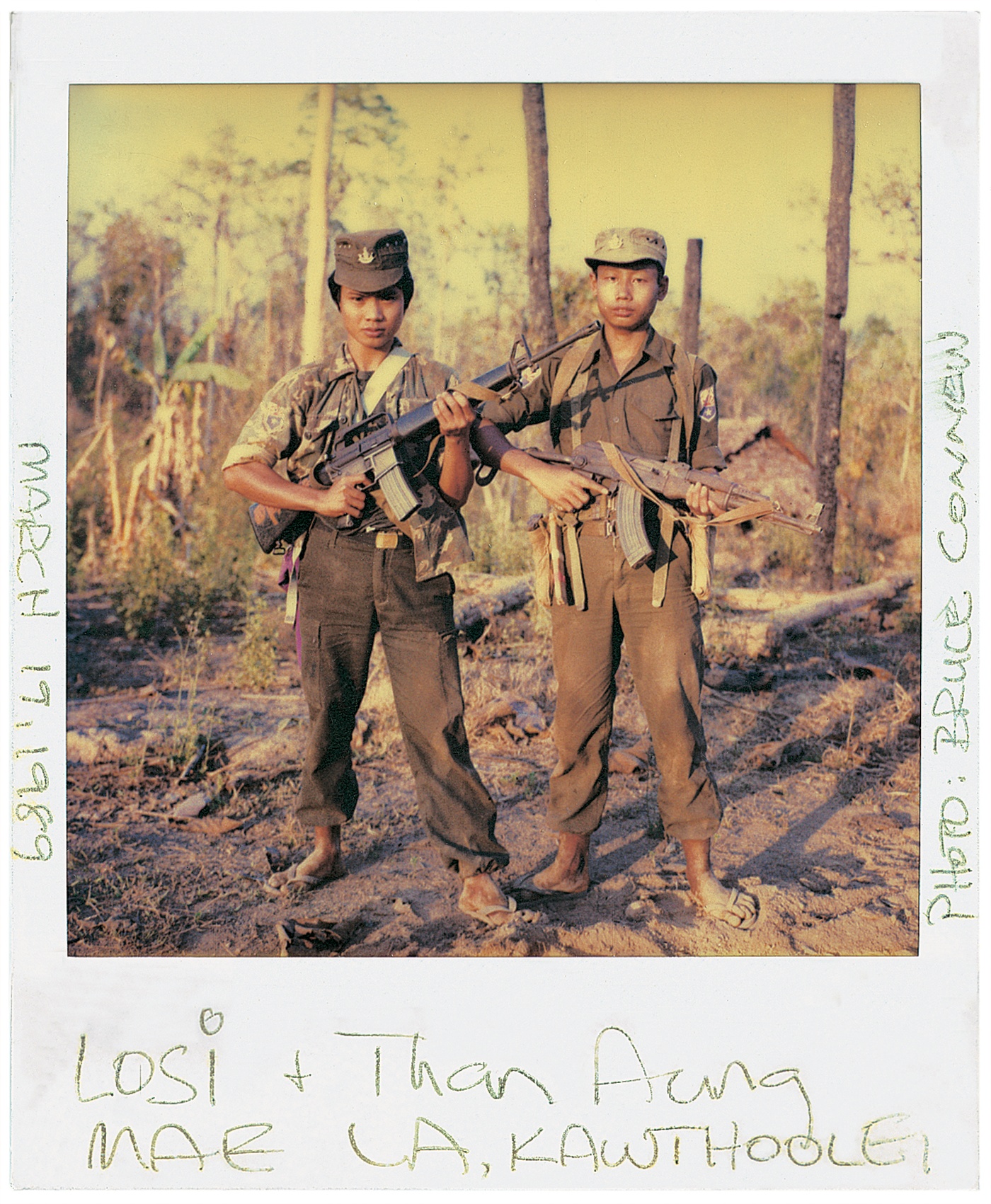

“. . . the two teenagers moved quickly together, entwining their arms for a photograph they must have known they would never see.”

book

‘On the way to an ambush’ was published by Victoria University Press, Wellington, New Zealand, and launched 22 April 1999 to a generous crowd at Unity Books, Wellington, the best bookshop in New Zealand.

“This is his record of time spent looking and thinking about what has been seen and what it might mean. Through a process I can only describe as an unfurling or unravelling, this war in Burma becomes a metaphor for Connew’s own life.” Peter Turner, past-editor, Creative Camera magazine.

out of print

exhibition & prints

‘On the way to an ambush’ was a 40-image exhibition at War Photo Ltd, Dubrovnik, Croatia, May-July, 2008. The work was almost an exhibition in 1999 at the National Library Gallery, Wellington, New Zealand, but fell foul of institutional re-structuring.

related writings

view all 87 works with print/price particulars

‘A random act’, a review by Stephen Stratford, May 1999

Stephen Stratford, now Quote Unquote bolg, wrote the following review of ‘On the way to an ambush’ for now defunct Grace magazine, May 1999. It gives some context to the book and its story.

‘A random act’

In his moving book, Bruce Connew reflects on the ambushes that lie in wait for all of us.

Bruce Connew’s ‘On the way to an ambush’ began as a photo essay about his time in 1989 with the Karen independence fighters in Burma, but in the 10 years since, as he mulled it over, it turned into a meditation on the randomness of death.

In 1987, his wife Barbara, from whom he was separated, was killed in a car accident while taking their son Tim and three friends to school. This painful story and its aftermath is interwoven through the story of the Karen’s war.

The two are unrelated, apart from Connew’s involvement in both, but from them he has wrought something extraordinary. In its unique combination of words and powerful photos, ‘On the way to an ambush’ (Victoria University Press) is one of the most moving books I’ve read.

At one point in the story, Connew describes how a soldier, Saw Dee, whom Connew had befriended, is killed by a rocket in the back while fetching water from a stream. As he lay on a table, wrapped in an olive-green plastic table cloth, “I looked down at him and shivered a little as I caught a picture of Tim, my son, prising open one of Barb’s eyes as she lay in her coffin two years before. At this moment—and I accepted that it was for me alone—these two quite separate and unforeseen deaths entwined.”

Both Barbara and Saw Dee had set about common, simple domestic tasks, and, at their own unrelated points in time, been targeted for doom.

“The randomness of it all appalled me. You live and you die, there’s no mystery to that, but there seemed something cruel about these deaths.” But, Connew, who lives in Wellington, is adamant that he wasn’t trying to force a connection.

“It just happened. There was no great flash of insight; more like word association, if anything.”

Even then, Connew didn’t see the connection as being part of a book. That started much later, in 1992, when he was working with his friend, the novelist Lloyd Jones. “I’d told him the story and he said I should make a book out of it.”

Lying on Jones’ couch and with the tape recorder running, Connew talked about Burma, and Barbara’s death and funeral. It took five days to finish his story. “Lloyd’s idea was to use the tapes as text for the photographs. But when we played around with the transcript, trying to take bits out and put bits in, it didn’t work. Another friend said, ‘You’re going to have to write this,’ and in 1994, I set about putting it altogether.”

The photos and text slipped into each other, along with letters and faxes: “It went easily—and I thought, my god, it does work. The ideas and thoughts were always there, but they cropped up more clearly as I worked. When I looked at the letters from Travis, an ex-SAS mercenary, and the kids’ faxes from home, I began to see the connections between them. For instance, being in Burma and getting a fax from my younger daughter Jane saying ‘We were in a car crash’ [fortunately, this time, there were only a few scratches], then seeing a soldier being killed and thinking, ‘Why him?’—it was a series of ambushes.

“After about the 35th draft, I laid out the text and photos, sequencing the photos starting with Barb’s smashed car. It’s a single image on its own—ambush, accident, death—it summed up what I wanted the book to explain.”

Connew then travelled to India with his eldest daughter Sally, and his partner, designer Catherine Griffiths, put the book together. Griffith’s design—which blends the words, photographs, faxes from the children and letters from Travis and others into something very much more than the sum of its disparate parts—is crucial to the book’s overall effect. “It’s not about exquisite photos,” says Connew, “it’s telling a story, giving the details.”

Deciding on the size of the book took a bit of time too: “We wanted a reasonable picture size but it also had to be small enough for readers to sit up in bed with—you can’t do that with a big picture book. It’s a book to read.”

Affecting though it is, ‘On the way to an ambush’ is not a grim book. There are many amusing minor characters, such as the English backpacker Laila he encounters in a dugout at the frontline, or Lieutenant Gringo who rides a motorbike home each night “from the trenches to his wife and three young children in the refugee camp, returning the following morning after breakfast, like a nine-to-five job. When complications arose, he would send home a note to say he’d be late back.”

Connew’s been doing documentary photography in Southland and this month he’s off to Israel, Jordan and the Balkans.

STEPHEN STRATFORD / 05.1999

view all 87 works with print/price particulars

On the way to an ambush #39 / A Karen soldier dresses in the trenches, Mae La, Burma, 1989

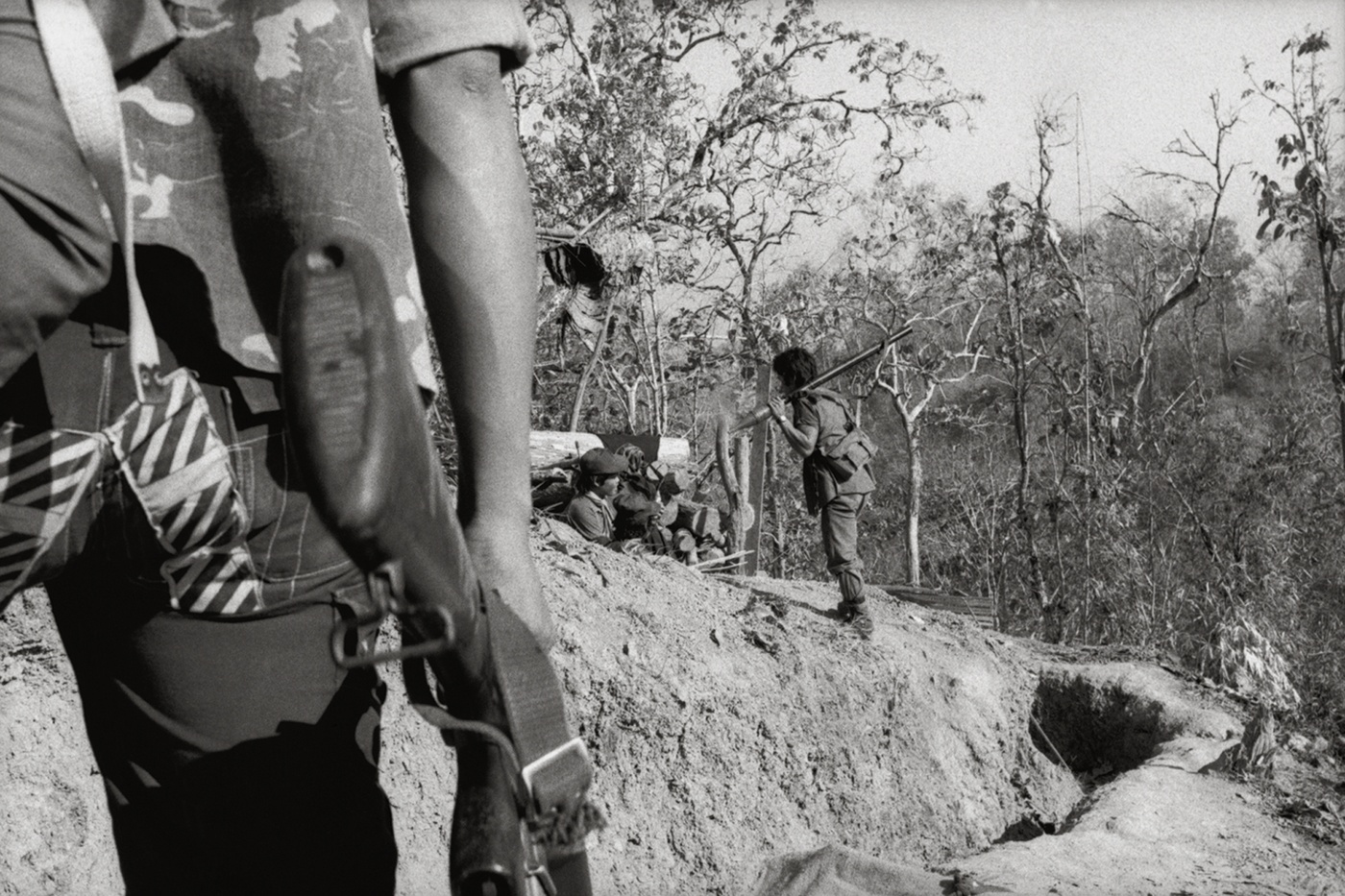

On the way to an ambush #56 / Karen trenches, Mae La, Burma, 1989

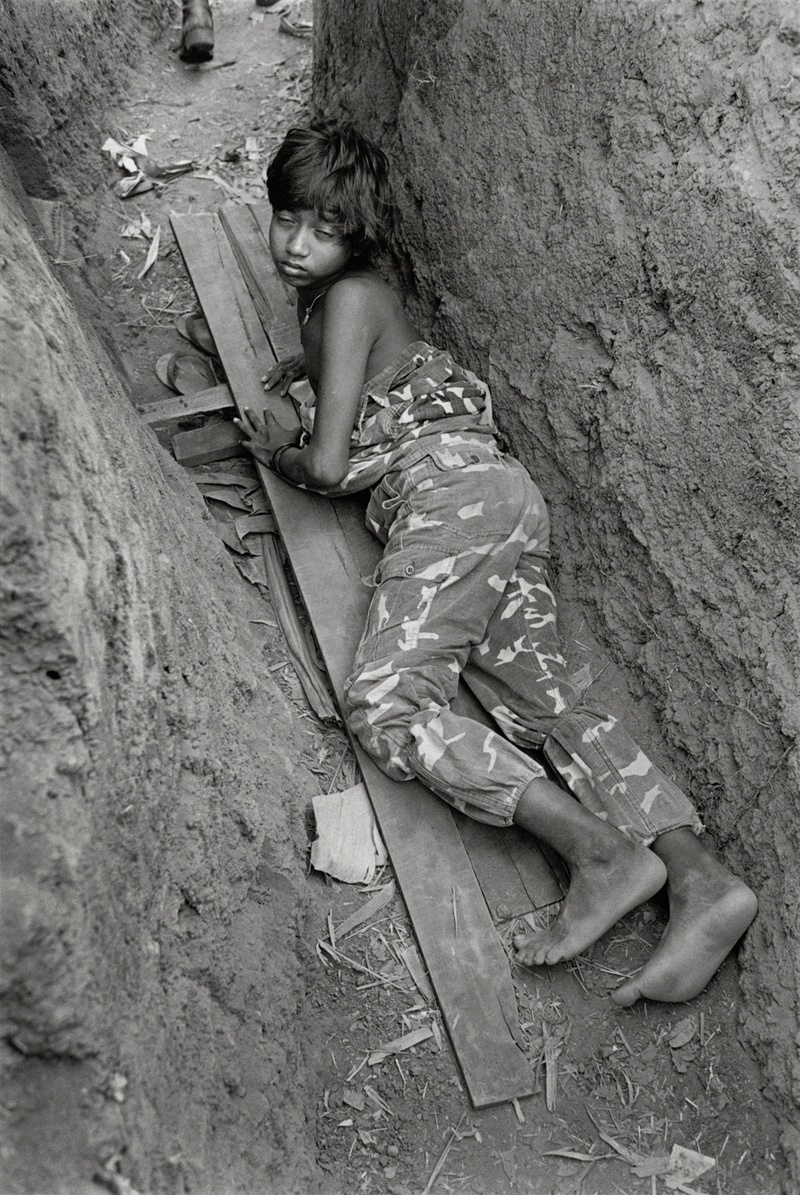

On the way to an ambush #65 / Saw Dee, a Karen soldier, Mae La, Burma, 1989

On the way to an ambush #7 / Travis’ Karen raiders at a Karen village, Burma, 1989